by Daniel Hathaway

Now in its second season, the Silent Film Festival has obviously attracted a following. The crowd gathered on Friday evening September 8 in Gartner Auditorium at the Cleveland Museum of Art so far exceeded expectations that attendees were asked to recycle their programs for the Saturday screening.

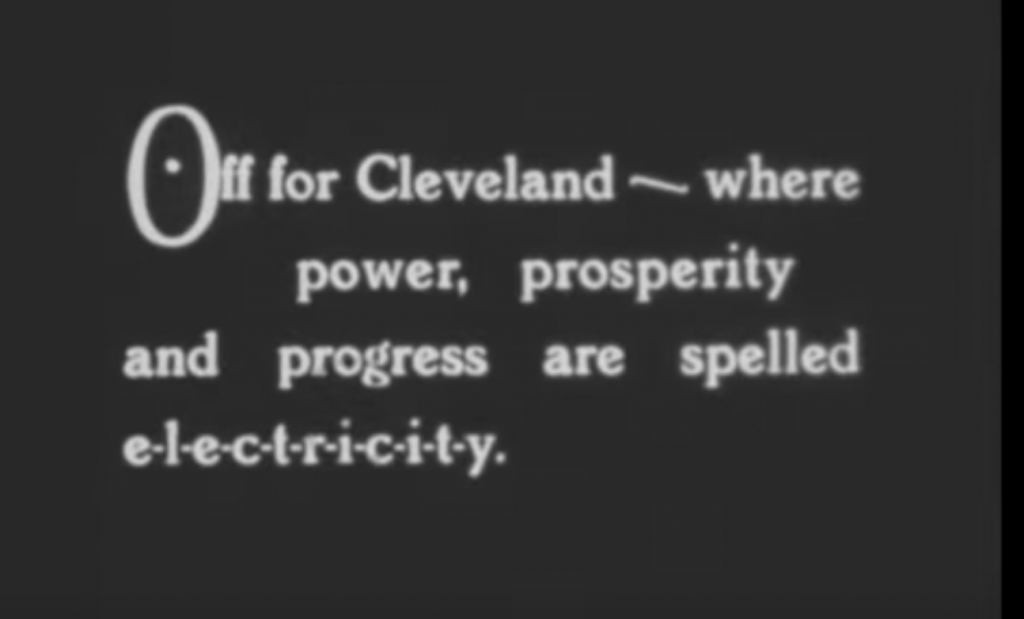

Two farm children living off the grid are flown to the big city by a friendly pilot and shown the wonders of power generation and distribution by a CEI executive, and the household application of electricity by the pilot’s sister, who has all the available mod cons at her disposal. (The aerial scenes enroute to the city are breathtaking.)

Published on ClevelandClassical.com September 19, 2023.

Click here for a printable copy of this article