by Daniel Hathaway

This evening at 7:30, Jinjoo Cho (pictured) will be featured in Barber’s Violin Concerto with BlueWater Chamber Orchestra at Church of the Covenant (previewed here).

At the same hour, Jeannette Sorrell will lead Apollo’s Fire in the second of four performances of “Fire and Joy: from Bach and Vivaldi” at Lakewood Methodist featuring Debra Nagy, oboe, Alan Choo, violin, & Nicole Divall, viola d’amore (read a preview here) in works by J.S. Bach and Vivaldi.

Also on Friday at 7:30, CIM Opera Theater presents the first of two performances of Handel’s Alcina in Kulas Hall (read a preview here), and Opera Western Reserve stages Carmen at Powers Auditorium in Youngstown.

For details of these and other events, visit our Concert Listings.

NEWS BRIEFS:

The Cleveland Institute of Music reports that Venezuelan pianist Gabriela Montero, famed for her improvisatory skills, will join its piano faculty in the 2024-2025 academic year. Montero gave a memorable performance on CIM’s Mixon Masters Series inn 2014, and most recently appeared in a special recital during Piano Cleveland’s International Piano Competition for Young Artists last July (read our review here).

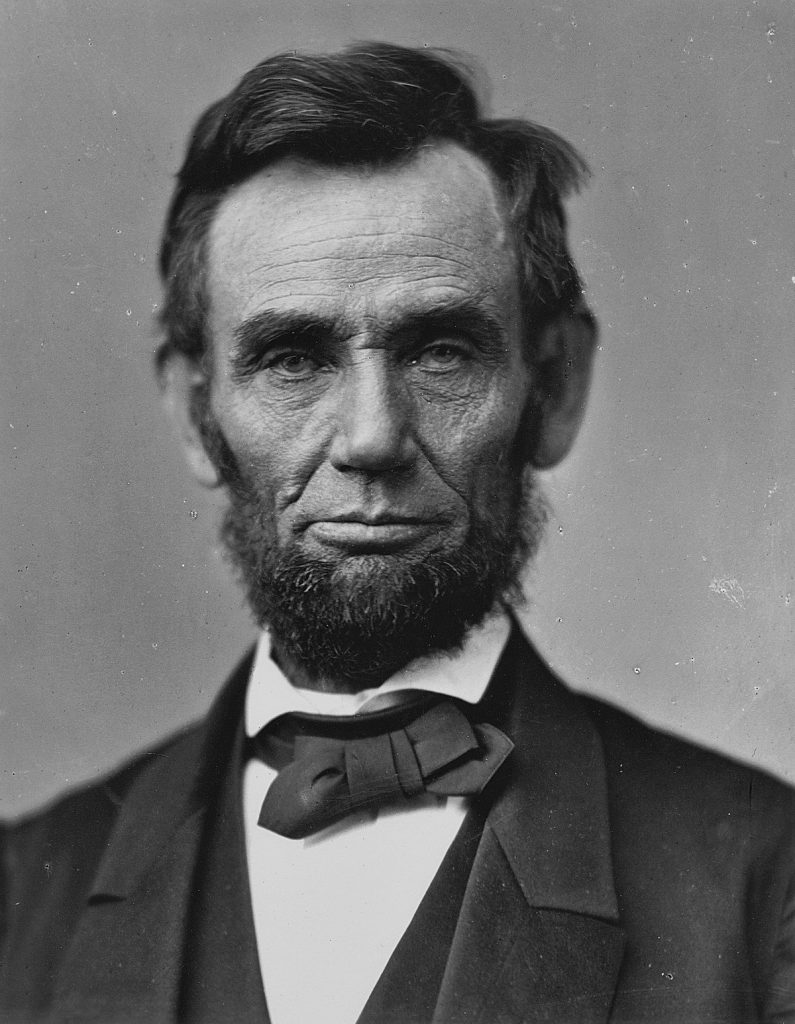

TODAY’S ALMANAC: Lincoln in Gettysburg

by Jarrett Hoffman

Moving forward to the 20th century, two pieces of music referencing that president or that speech had their premieres on this date. We begin with Daniel Gregory Mason’s Lincoln Symphony, which was first heard at Carnegie Hall on November 17, 1937 in the hands of John Barbirolli and the New York Philharmonic.

In the opinion of Olin Downes, who reviewed the premiere for The New York Times, the more heavily programmatic movements were less successful, not to mention that “accents of other composers” such as Brahms, Franck, and Elgar made it feel not entirely fresh. However, he went on, a convincing and eloquent originality could be seen in the last movement, “where the suggestion is of mood rather than events or external characteristics…”

Listen to the symphony here (the finale begins at 23:18) from Barbirolli and the New York Philharmonic in a recording taken from airchecks, only intended for documentation.

Again The New York Times documented the premiere. Raymond Ericson described the work as “dignified and effective — a noncontroversial, useful piece for patriotic concerts.”

Perhaps its text setting deserves a special plaudit. In program notes for a recording by the Seattle Symphony, Steven Lowe writes, “It is always a challenge for a composer to set prose, rather than the customary poetry, in a song cycle, and Diamond’s imaginative setting balances the rhythmic freedom of recitative with the structured cadence of an aria.”

Click here to listen to that recording from Seattle. The orchestra is led by Gerard Schwarz, and is joined by the Seattle Symphony Chorale, the Seattle Girls’ Choir, the Northwest Boychoir, and baritone Erich Parce.

Back to Gettysburg and the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, it’s interesting to note that Lincoln’s address was not at all slated to be the main feature of the event.

That honor belonged to a man known at the time as a great orator, Edward Everett, who spoke for two hours (not atypical at similar events of the era) in delivering a 13,607-word speech. It was apparently impressive and polished.

According to one eyewitness, Lincoln spoke “with a manner serious almost to sadness.” He was also sick with what would soon be diagnosed as a minor case of smallpox. Wrote his assistant secretary John Hay, the president’s face had a “ghastly color,” and he was “sad, mournful, almost haggard.”

He needed only 271 words to enter into the annals of oration.