by Mike Telin

As the title suggests, the program featured a healthy dose of music for the piano. And Shuai Wang proved to be a worthy interpreter with her impressive and committed performances throughout the evening.

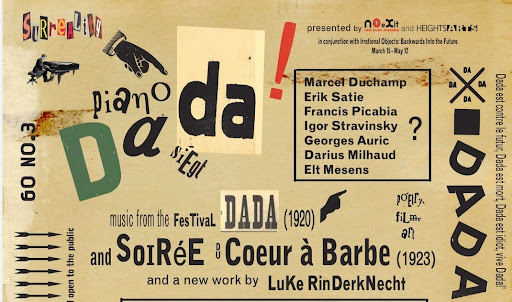

After Tristan Tzara’s short 1920 film The Song of a Dadaist, Wang captured the audience’s attention with Francis Picabia’s La Nourrice Américaine – fast (1920). Here the performer is instructed to select three notes at random and, essentially, quickly poke at them from one end of the keyboard to the other and back again.

Wang’s performance of Darius Milhaud’s jazzy dance piece Caramel Mou (1920) was full of color and dynamic contrast. And she perfectly captured the many moods of Georges Auric’s Adieu New York! (1919), an off-kilter foxtrot that brings to mind the soundtrack to a mime show in Central Park.

Next came three original poems by No Exit’s own Gunnar Owen-Hirthe, James Praznik, and Timothy Beyer. The poems were read simultaneously by the authors, humorously creating a tower of Babel in real time — Praznik was the last man standing.

Wang was joined by pianist Rob Kovacs for Erik Satie’s Trois Morceaux en forme de Poire (“Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear”). The players brought vivid imagery to the work’s seven — yes, seven — movements, especially the childlike Prolongation du même, the esoteric Morceaux 1, the tuneful Morceaux 2, the calm dance music of En plus, and the concluding slow waltz Redite.

Wang’s playing was thoroughly enjoyable during Belgian artist and writer E.L.T. Mesens’ Drie Composities Voor Klavier — Nos. I, II, and IV (No. III has been lost). And in Marcel Duchamp’s Musical Erratum was originally conceived for three voices, to be sung by the composer himself and his sisters Yvonne and Magdeleine, and was later adapted for the piano. Wang brought out Duchamp’s sharp, pointed writing in the outer movements and the legato of the middle movement.

This was followed by the full No Exit ensemble version of the piece, where all three movements were played simultaneously. Here Luke Rinderknecht exchanged his vibraphone mallets for a stuffed animal.

In 1916 poet Hugo Ball presented his sound poem Karawane at Cabaret Voltaire. In honor of that occasion No Exit created a black and white film with all of the members in sunglasses while James Praznik thoughtfully recited Ball’s text.

Wang and Kovacs returned for Stravinsky’s Trois Pieces Faciles Quatre Mains, a pedagogical piece for piano four hands written for the composer’s children. The “Three Easy Pieces” take about three minutes to perform, and the pianists made the music — which at times is not all that easy to play, especially the demonic-sounding Waltz — sound like a masterpiece. It also served as a welcome ear cleanser.

The evening concluded with the world premiere of Luke Rinderknecht’s Moon fight hearing aid. The work utilizes many dadaist techniques and ideologies, beginning with the full ensemble all turning pages, very fast — a fake rehearsal?

Dance hall beats became the work’s driving force while violinist Cara Tweed opened a can of soda. Wind-up ducks traversed a snare drum while Rinderknecht ate an apple.

The piece includes musical snippets of Für Elise, the Jeopardy! theme, Fly Me to the Moon, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6, Grieg’s In the Hall of the Mountain King, and the final movement of Mozart’s “Haffner” Symphony, as well as finger snapping and even some whirly tubes.

All the while, two dancers — Melissa Ajayi and Julia Dillard — rose from the audience, rolled onto the stage, and danced in each other’s arms. Wang appeared with a trombone (no sound was made). The dancers’ movements evolved into a slow-motion barroom brawl. Driving chord progressions and drum beats played on while Timothy Beyer read from Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret from the back of the gallery.

The brawl transformed into a horseback ride, with the rider wielding an imaginary lasso. Then, back to the page turning.

Moon fight hearing aid is full of wonderfully head-scratching moments that perfectly capture the essence of No Exit’s Year of Surreality.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 22, 2024.

Click here for a printable copy of this article