by Kevin McLaughlin

CLEVELAND — On Friday evening, Sep. 26, before The Cleveland Orchestra opened its 108th season, Music Director Franz Welser-Möst joined President and CEO André Gremillet onstage for a conversation previewing the next ten programs. With a reenergized music director, an impressive slate of repertoire, soloists, and guest conductors, the Orchestra’s 2025-26 season looks especially bright.

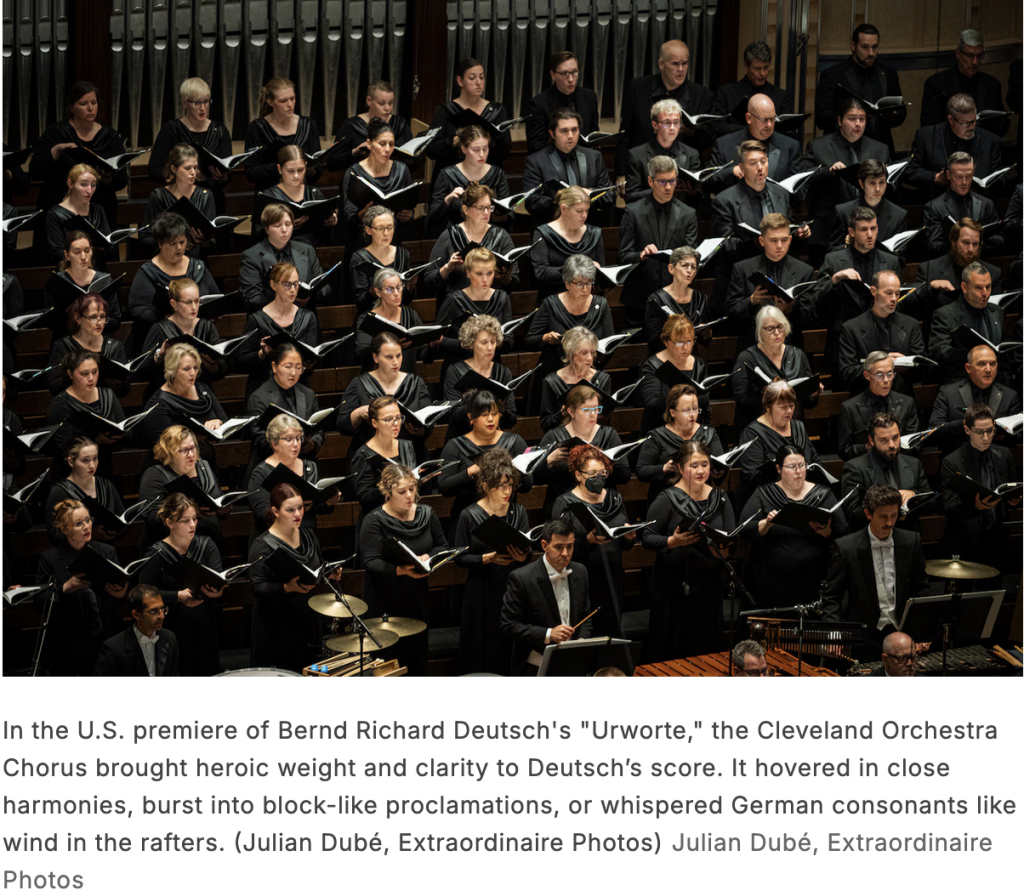

Austrian composer Bernd Richard Deutsch has become a familiar figure here in Cleveland under Welser-Möst. During his tenure as the Daniel R. Lewis Composer Fellow from 2017 to 2020, the Orchestra introduced his organ concerto “Okeanos” and later, his large orchestra work “Intensity.” On Friday came a third U.S. premiere, “Urworte” (2024). Such partnerships nourish everyone: the composer gains a champion, the orchestra fresh music, and the repertoire welcome enrichment.

Some works sidle into the hall. Deutsch’s leviathan “Urworte” erupts with a low, seismic rumble, as if the earth itself were opening up. Booming percussion and a contrabassoon rhapsody, deliciously played by Jonathan Sherwin, announce the journey. From there, the Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus traced nothing less than the span of a human life. The text is Goethe’s late work “Urworte” — five philosophical poems naming the primal forces that govern human life: Daimon (Demon), Tyche (The Accidental), Eros (Love), Ananke (Necessity), and Elpis (Hope).

The score gives a nod to its forebears — Schoenberg’s monumentality and Stravinsky’s rituals. But in fellow Austrian Welser-Möst’s hands it also spoke Deutsch: sober yet playful, luminous yet unafraid of shadow. At 55 minutes, the piece may be overlong, but it rewards the listener with moments of stark beauty, sudden volatility, and unexpected tenderness.

Strauss piles on chromatic perfume in Salome’s Dance until the air grows thick, while Ravel’s sultry theme in Boléro, repeated without relief, risks wrecking the mood. Still, both works on the second half proved remarkably effective, and after the weight of the Deutsch, they felt almost like encores.

The “Dance of the Seven Veils” is less of a dance than a ten-minute orchestral seduction. Strauss lavishes effect upon effect, and the result is irresistible. Welser-Möst leaned in, goading Frank Rosenwein’s sinuous oboe, Afendi Yusuf’s supple clarinet, and strings at their most voluptuous into a wave of sensual promise — or at least the suggestion of bare flesh.

Ravel’s “Boléro” remains a marvel of headlong compulsion. From the first taps of the snare drum — steady and unyielding — the piece builds by layering color upon color. Each solo voice adds its shade and attitude from an airy flute (Joshua Smith), to a slyly curling clarinet (Yusuf), and a broadly-singing trombone (Brian Wendel).

Underneath it all, the snare ticked like a metronome, organizing yet not governing the long crescendo. Under Welser-Möst’s patient direction, the musical arc was measured and hypnotic, even a little terrifying. By the time brass and percussion roared in fury, the audience had been swept along on a grand, unbroken wave of tension without release — absurdly simple, irresistibly effective.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 2, 2025

Click here for a printable copy of this article