by Mike Telin

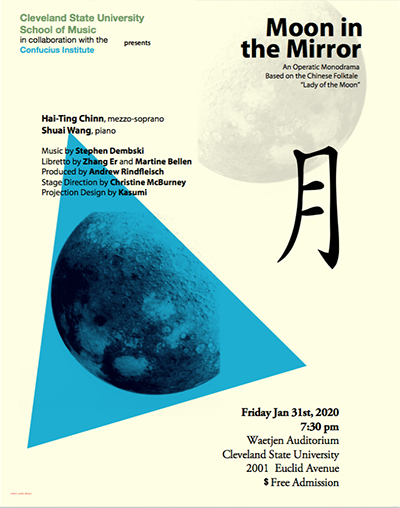

On Friday, January 31 at 7:30 pm in Waetjen Auditorium, the Cleveland Contemporary Players Series in collaboration with the Confucius Institute at Cleveland State University will present Moon in the Mirror, with mezzo-soprano Hai-Ting Chinn and pianist Shuai Wang. Produced by Andrew Rindfleisch, the 40-minute operatic monodrama features music by Stephen Dembski, a libretto by Zhang Er and Martine Bellen, stage direction by Christine McBurney, and projection design by Kasumi. The free performance will also include Chen Yi’s Northern Scenes for solo piano.

Moon in the Mirror received a concert version performance by Hai-Ting Chinn and pianist Vicky Chow in October of 2015, and since that time, the creative team has been searching for funding and collaborators to fully stage the 40-minute work.

Andrew Rindfleisch, who serves as Professor of Composition and Director of the Cleveland Contemporary Players at Cleveland State, said it was librettist Zhang Er who first presented him with the idea of producing the work. “She was aware of the Confucius Institutes that are housed in a handful of universities in the country, and as it turns out, there is a Confucius Institute at Cleveland State. They help to foster projects that combine both Chinese and American cultural collaborations, and this seemed like a project that I could take to them.”

Based on the ancient Chinese legend of The Lady in the Moon, Moon in the Mirror is presented in seven sections that span a 20-hour period:

In “The Dream,” Ren awakens from a nightmare in which she’s Moon Lady and, foggy from the experience of sleep, she can’t remember who she is.

In “The Loss,” at dawn, she awakens again, now in a puddle of blood from a miscarriage. She questions her life choices and sees that Yi, her husband, is, as usual, nowhere to be found.

In “Fairytale” she channels her agony through dance, choreographing the story of Chang E that she has dreamed, a story that stayed with her from childhood.

After dancing herself into exhaustion, in “Mortality,” feeling perspicacious, she is convinced that she can be immortal like the story’s demigoddess, not the mortal gray-haired woman who she is becoming.

In “The Moon” she makes up short poems as she looks through her window at the moon, and she decides to take a journey to the moon.

In “Greetings, Goddess!” she ingests the illicit magic elixir of immortality like the Moon Lady’s — a potion of pills and booze.

At midnight, in “Space Travel,” the full moon is high, and she feels it calling; she is answering it. She dances her Moon Lady dance, flying among stars toward the rising moon, singing.

There were two things the composer found striking in the libretto. One was how short excerpts from works by female poets, including Emily Dickinson, were interleaved. The second was the inclusion of a traditional child’s song in Mandarin. “I’ve set it extremely simply and it is one of my favorite parts of the score.”

Dembski said that when the Cleveland opportunity arose, he and Hai-Ting revisited the vocal part and made some changes. “I’ve written quite a bit of music in the intervening years, so she knows the piece much better than I do.” This opportunity also reunites teacher and student: Rindfleisch studied with Dembski at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. “He’s gone on to do great things and turned into a wonderful colleague in so many ways,” Dembski said.

If you read director Christine McBurney’s resume, you will find that she’s pretty much done it all, including staging Telemann’s Canary Cantata (Funeral for a Dead Canary) last season for Apollo’s Fire. That said, Moon in the Mirror has presented her with many new challenges.

“I’ve directed musicals, but it’s not a musical. I’ve directed plays, but it’s not a play — and it’s not a concert piece either,” McBurney said during a separate telephone conversation. “It’s sort of a hybrid that is somewhere between presentational and representational, and that’s what Hai-Ting and I are going to find together.”

The director noted that while Waetjen Auditorium is a beautiful space, it is a concert hall. “We don’t have the full capabilities of a theater, and I think it’s wise not to pretend that we do,” she said. “So a less-is-more, stripped down, bare bones approach is what I am thinking. That way the focus can remain on the music, and the theatrical elements can aid in the storytelling without competing with it.”

Although McBurney would not say that Moon in the Mirror has a feminist slant, she did note that it is about a modern woman who suffers a miscarriage, with her husband nowhere to be found. “But my job is to tell the story of this human being so that other human beings can see themselves from another point of view. So I’m not going into it with an agenda.”

When asked why she wanted to take on the project, her answer was quick and clear. “I love opera and I’ve always wanted to direct one. And I thought this would be a great dipping of my toes in the water of that world. I’m looking forward to collaborating with Hai-Ting. She knows this so much better than I do, so I’m not going to come in and say, ‘Okay, here’s what you’re doing.’ I’m not like that. But I do need to come in with a blueprint because our time is so short.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 27, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article