by Daniel Hathaway

It’s time for the annual celebration of Hallowe’en, and probably also time to put that apostrophe back in its name, which is a contraction of “All Hallows Eve,” or the day before the Christian feast of All Saints’ Day. So on Saturday there will be “ghoulies and ghosties, and long-leggedy beasties, and things that go bump in the night” out and about, and on Sunday, holy people to remember.

A variety of scary mix tapes is available, but Dark Classical, one of the better collections to listen to on Hallowe’en, will give you an hour and 45 minutes worth of thrills and chills while you’re waiting to pass out sugary treats.

Everyone has their own favorite hair-raising music, and comments on the aforementioned collection have lamented the omission of Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain, and proposed adding Schnittke’s Requiem, and the “Dance of the Knights” from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet.

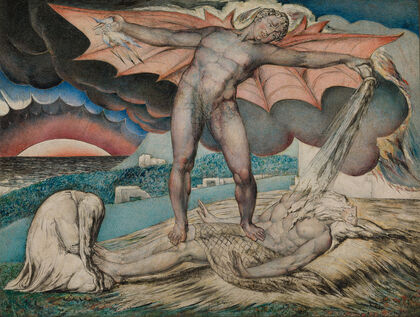

My own recommendation for generating goose bumps is “Satan’s Dance” from Ralph Vaughan William’s Job: A Masque for Dancing, based on drawings by William Blake (above, Satan smiting Job with boils). The composer dedicated his 1930 work to conductor Sir Adrian Boult, who leads it here with the London Philharmonic at the age of 83. (Satan enters around 4:12).

On the All Saints’ Day side of the weekend, you could hardly do better than listen to the third movement of Heinrich Schütz’s Ein musikalische Exequien, a setting of the Song of Simeon (Nunc Dimittis) overlaid by a trio of soloists singing “Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord, for they rest from their labors.” Follow the score in this performance by Philippe Herreweghe and La Chapelle Royale. Incidentally, Schütz died on October 31 in 1672.

On this weekend in 1517, the German Augustinian monk and university professor Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, an act that many regard as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. Luther, a complicated figure who composed his own music and set vernacular hymn texts to secular tunes, has inspired many documentaries. Here’s one by PBS travel guru Rick Steves, himself a Lutheran of Norwegian extraction.

That leads us to the later German organist, composer, and choral conductor Hugo Distler, who died at his own hand in Berlin on November 1, 1942. Though he suffered depression over the fate of his colleagues during the Third Reich, as Nick Strimple writes in Choral Music in the Twentieth Century, “it appears that he saw the futility of attempting to serve both God and Nazis, and came to terms with his own conscience unequivocally.”

Distler wrote a great deal of neo-Baroque music for organ and choirs. For just a sampling, listen to his motet Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied as sung by the Oberlin Collegium Musicum under Steven Plank on a Trinity Cathedral Brownbag Concert on May 4, 2011.

A work particularly suitable for this Hallowe’en/All Saints’ weekend is Distler’s Totentanz, a 14-movement choral cycle based on poetry by Angelus Silesius. Between the movements, Distler interleaved a friend’s paraphrases of poetry from the Lübecker Totentanz, “a dialogue in Middle Low German between Death and its victims.” The Netherlands Chamber Choir performs the 1934 piece here.