by Daniel Hathaway

Bassett has had the opportunity to perform Messiah frequently with Cleveland’s baroque orchestra in the twenty years since it first presented the work. “In fact, I believe I’m the only person — and that includes Jeannette Sorrell — to have played in every Messiah that Apollo’s Fire has done.” (One set of performances the ensemble gave was led by a guest conductor.)

“You never have as much time to spend in a pre-concert talk than you think,” Bassett said, who has filled this role once before for Apollo’s Fire, “but I plan to talk about the entry of timpani into Western music and how the instruments became such an integral part of high baroque music.

“Even though I don’t play that much in Messiah, the writing is wonderful. Timpani are reserved for particularly important spots in the piece and it shows what a turning point the oratorio represented in timpani writing at the time. It came right at the end of the Guild period for trumpeters and drummers and at the beginning of the transition into a symphonic sound. The drums were getting bigger, the quality of the instruments was getting better and players were actually specializing in playing timpani.”

Originally outdoor instruments with military connections, timpani began to come in from the cold early in the seventeenth century. “The earliest known written example is in Lully’s 1675 opera, Thésée, and there are written parts for timpani in Purcell’s music,” Bassett said. “Most people conclude that the guys who were coming in and playing them on occasion were improvisers. The big cadences in Messiah are just indicated by whole notes, so there are some fun spots to improvise within a limited range. You get to feel for one minute out of a two-and-a-half hour piece that you’re important!”

Lest anyone think that those important bursts of activity from the timpanist are easy to accomplish, Bassett went on to explain a few of the vagaries of playing on period drums — and moving them from one venue to another.

“Timpani react quickly to weather changes. The trick is to predict which way things are going to go. Churches are heated and dry, but as the drums warm up, the heads dry out and they go higher in pitch. Stabilizing the copper ‘kettles’ is important because the air inside takes a long time to come up if when the metal is cold. Then the audience arrives and breathes and the performance space gets warm and humid. Just about the time that they stabilize, they go down in pitch because of the added humidity.

“People are stunned when they find out how fast a change in humidity can happen — sometimes within ten measures. I take my intonation very seriously, and it never helps anyone if the timpani are out of tune.” Bassett tunes his drums by turning six keys that tighten or loosen the head skins. Balancing the tension is called ‘clearing the head’. “They’re pretty simple, but they’re still finicky instruments,” he noted, adding that the timpani entrances in Messiah can be 40 to 45 minutes apart, and a lot can happen in between.

And then there’s the choice of sticks. “Timpani reach their full glory in a space that allows the reverberation to move the sound around and interact. Period timpani with skin heads produce a drier sound than modern heads, but also a sound that’s warmer, darker and ‘bass-ier.’ Even though the drums don’t ring as long, they’re so rich in their sound that you have to use hard sticks. I alternate using three sets of sticks.”

Though Matthew Bassett has played Messiah with Apollo’s Fire more times than he’s stopped to count, he looks forward to every performance. “When you revisit something you’ve spent a lot of time with in the past, there’re always new things to discover. There are decisions to be made, both obvious and less obvious. I have a very distinct plan for every single note and rhythmic pattern, but I leave it open because you’re playing with different trumpeters and you have to see how it’s going.”

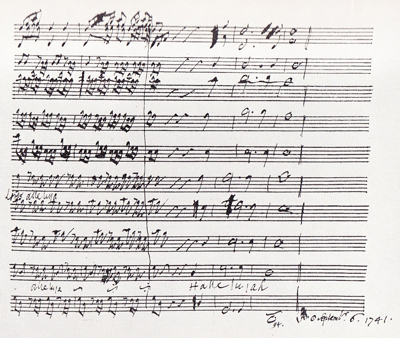

Handel’s ms. of the end of the Hallelujah chorus, 1741.

How has Jeannette Sorrell’s concept for Messiah evolved over the years? “Her vision of how she perceives the piece has certainly grown,” Bassett said. “The fundamentals were in place early on and it was a matter of gradually attracting the players she needed to bring it to pass. Now, it’s so relaxed. People know how she likes to shape things, and they can be more flexible in performance. I think it was George Szell who said, ‘spontaneity is the result of meticulous preparation.’ Trusting in each other gives people the freedom to ‘go for it’ with a little more inspiration in the moment. There’s always been a clarity and cleanness to the way we play, but there’s more depth and breadth to how we do it now.”

Jeannette Sorrell, conducts Apollo’s Fire and Apollo’s Singers in Handel’s Messiah with Meredith Hall, soprano, Amanda Powell, mezzo-soprano, Ross Hauck, tenor & Jeffrey Strauss, baritone on Thursday, December 11 at 7:30 pm in Trinity Cathedral; on Friday, December 12 and Saturday, December 13 at 8:00 pm at First Baptist Church in Shaker Heights; on Sunday, December 14 at 3:30 in St. Mary of the Falls Church in Olmsted Falls; and on Monday, December 15 at 7:30 at Fairlawn Lutheran Church. Matthew Bassett’s pre-concert talks begin one hour before each concert. Lengths of performances vary (visit the orchestra’s website for details).

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 8, 2014.

Click here for a printable copy of this article