by Robert Rollin

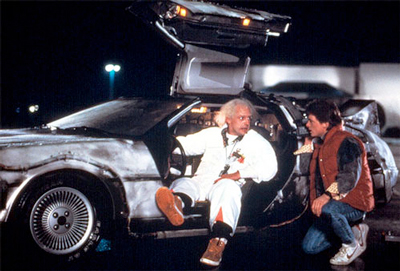

Back to the Future, starring the exceptionally talented Michael J. Fox, Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin Glover, is very likely the best time travel science fiction movie ever made. It spawned two equally excellent sequels.

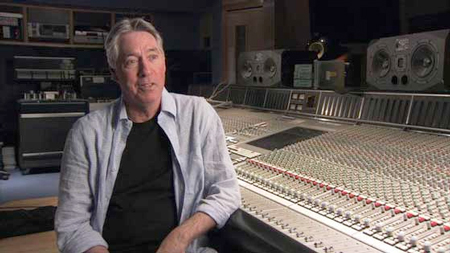

Before his work on Back to the Future, composer and New York City native Alan Silvestri had written the score to the low-budget comedy The Amazing Dobermans in 1972. During the 1970s, he composed the music for TV’s highway patrol hit CHiPs. On the strength of his reputation as a composer of rhythmically exciting action scenes, he teamed up with director Robert Zemeckis for the megahit Romancing the Stone (1984), and the two began an 18-film collaboration that has lasted over 30 years.

With Steven Spielberg acting as senior Executive Producer for Back to the Future, it’s no surprise that its technical production values are exceptional. The imaginative screenplay by Zemeckis and Bob Gale also contributed to the movie’s success, as did Silvestri’s exceptional score. In a Billboard Magazine article published last June, Silvestri explained that he had to compose 20 extra minutes of music for the current orchestral tour, which was launched by a consortium that included Film Concerts Live!, IMG Artists, and Silvestri’s agency Gorfaine/Schwartz. He also indicated that he returned to the music of the film to extract themes that he could develop further.

This new music appeared in the form of an “overture” that started before the credits rolled on to the screen, and later, in a position similar to an interlude between acts in an opera — the opening 23 minutes originally had no music. Silvestri also added music to the opening titles, to the scene in Doc’s lab early in the film, and to the dinner scene with the family.

Effective filmmaking has always been a team effort, and Back to the Future’s strength derives not only from Silvestri’s excellent score, but also from a gifted sound editor and production crew. Never once is there a moment when the elaborate score, dialogue, sound effects, or the added rock songs conflict with one another. Even with the newly added music for the concert version, production values are exceptional.

Silvestri played drums and guitar in his early career, and his score displays a remarkable sensitivity to percussion sounds. These include cymbal crashes, piercing slapstick entries, ever-present timpani and bass drum effects, prickly xylophone sounds emerging from complex textures, fast and delicate piano entrances often played against sustained instrumental backgrounds, and ethereal use of sustained vibraphones.

Much of the composer’s bag of tricks comes from conventional scoring techniques. Beyond his complex textures, Silvestri employs sudden fp chords that move immediately into huge crescendos. This kind of dynamic manipulation adds further excitement to his action-packed score. His use of majestic themes to represent the excitement of time travel certainly brings to mind similar passages in John Williams’s Superman score. Silvestri’s textures are generally thick and complex, but his infectious sense of rhythm and his personal treatment of percussion and brass help him emerge as an original film music voice that will continue to fascinate listeners for years to come.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 15, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article