by Mike Telin

On May 15, the final Fridays@7 of the season will include the Widmann and Dvořák. At 6:00 pm the pre-concert performance will feature three-time Latin Grammy nominee Jovino Santos Neto performing improvisations on Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony and on music from emigration movements across the world. For the post-concert party in the Grand Foyer, Santos Neto and friends will perform contemporary Brazilian bossa novas in a blend of European harmonies, African rhythms, Middle Eastern modes, and American jazz. And jazz vocalist Vanessa Rubin and pianist Sullivan Fortner will perform in the Severance Restaurant.

In March of 2011 we visited The Cleveland Orchestra Archives and discovered that Antonín Dvořák had a special relationship with the orchestra. The Archives house a fascinating collection of Dvořák Memorabilia. The story of how this collection found its way to Cleveland is the touching narrative of a relationship that developed over fifteen years of correspondence between Dvořák’s son, Ottokar, and Mrs. Emil Hess, who with her husband operated the Hess Bakery for more than fifty years. Born in Bohemia, Mrs. Hess came to Cleveland in 1907 with her husband and was a huge fan of Antonin Dvořák and his music.

But it was not music that brought Ottokar and Mrs. Hess together. According to an article by Ethel Boros in The Plain Dealer (January 28, 1964), “(Ottokar) Dvořák originally wanted to correspond with someone in America because he was a stamp collector. He advertised in a Czech magazine and Mrs. Hess answered his letter,” and thus the two became regular pen pals.

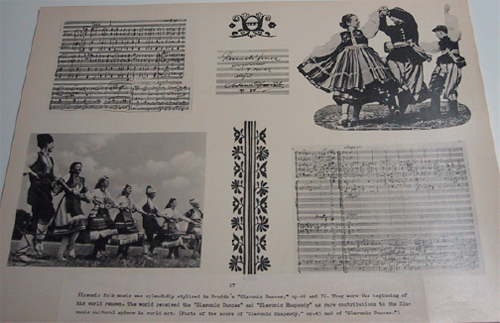

The Slavonic Dances

The PD article goes on to say that “Mrs. Hess knew from friends and relatives still living in Czechoslovakia of the great shortages that existed there after World War II. She sent hundreds of food and clothing packages to them, and to the Dvořák family as well. Since she had expressed so much interest in the composer and his music, the Dvořák family sent her whatever mementos they could, for pride would not allow them to accept gifts without presenting something in return.”

Though Ottokar Dvořák died in 1960, his widow continued corresponding with Mrs. Hess, who at one point told Cleveland Orchestra program annotator and archivist Klaus George Roy of her concern about Mrs. Dvořák, who had recently had her gallstones removed. “She has no appetite and I am so worried about her.”

Mr. & Mrs. Hess had been in conversations with The Cleveland Orchestra about donating the Dvořák memorabilia to its archives. This came at the suggestion of their eldest son, Cleveland musician Emil Hess, Jr., before his death in 1962, and the collection was officially received by The Musical Arts Association in February of 1964. The gift, as noted in The Cleveland Orchestra’s program book for April 9-11, 1964, was made especially because “Czech music is so often heard in authentic performances at concerts by the orchestra.”

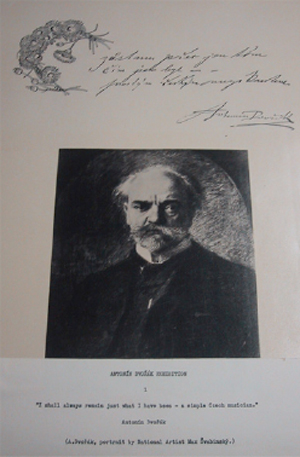

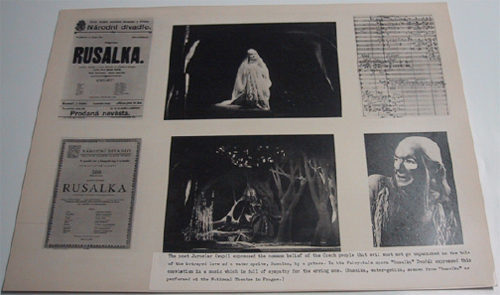

The opera Rusalka

Known as “The Emil Hess, Jr. Collection of Dvořák Memorabilia,” the collection includes “a copy of the Dvořák Centennial Bust (1941); a rare album of 60 large loose-leaf pages published in Prague in 1954 for the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death, lavishly illustrating the history of Czech music; some postage stamps with Dvořák’s picture; a variety of photographs of the Dvořák family, with one portrait autographed by the composer in 1903; and a pair of Dvořák’s own pince-nez spectacles” (Cleveland Orchestra program book, April 9-11, 1964).

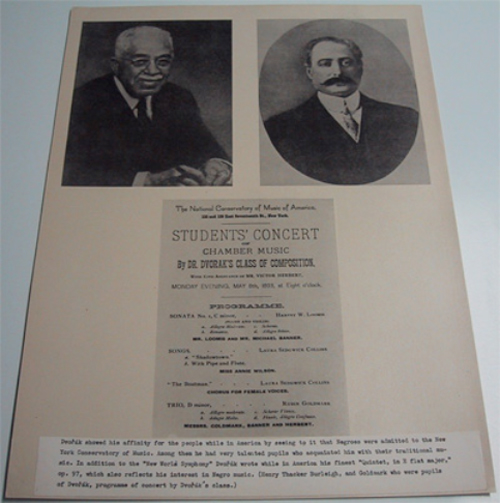

Students of Dvořák in recital, including Harry T. Burleigh

In keeping with the theme of communication then and now, what would have happened if Ottokar Dvořák had been able to join the Listserve of the American Philatelic Society in order to seek out Americans interested in stamp collecting? For one thing, he might not have met Mrs. Emil Hess — we found no evidence that she had any interest in that hobby.

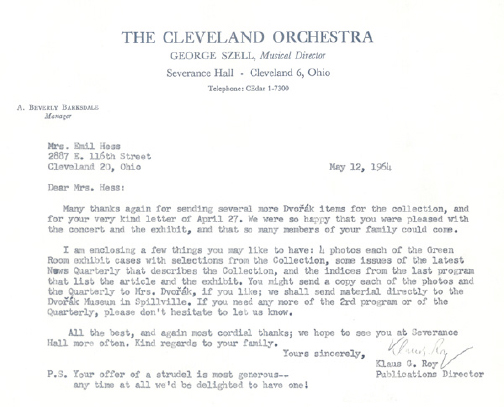

Letter from Klaus G. Roy to Mrs. Hess. Note the reference to strudel at the end.

Antonin Dvořák historical plates (publisher unknown, no date) and letter from Klaus G. Roy to Mrs. Emil Hess, 1964, from the Emil Hess Jr., Collection of Dvořák Memorabilia (The Cleveland Orchestra Archives) courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives, Deborah Hefling, archivist.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 15, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article