by Jarrett Hoffman

Next week, from May 15-19, Peled and guest conductor Mélisse Brunet will make their debuts with CityMusic Cleveland in five free concerts around the area to conclude the ensemble’s 15th season.

The title “Hidden Gems” certainly describes three of the four works on the program: Fanny Mendelssohn’s Overture in C, Saint-Saëns’s Symphony No. 2, and Kodály’s Dances of Galánta.

Not so for Saint-Saëns’s First Cello Concerto. “It’s a piece that we all play as teenagers — one of the first we encounter as quote-unquote serious cellists,” Peled told me during a trip to Europe, where he was to perform in Romania and Austria. For him, the Saint-Saëns was also one of the first concertos he performed with orchestra. “I will never forget the feeling of that first chord, and after that the explosion of emotion and the mastery of cello writing,” he said.

Peled is serious about doing his research when preparing a piece. I asked him to break down that process for the Saint-Saëns. “The only big Romantic concerto that was written before this was the Schumann in 1853, but nobody really played it, and Schumann never heard it during his lifetime,” Peled said. “So the Saint-Saëns in 1872 was really the first major cello concerto where a Romantic composer said, ‘I think the cello is a soloistic instrument.’”

The Lalo and Dvořák concertos followed, then Shostakovich’s First Concerto in the 20th century. “But many composers still consider the Saint-Saëns to be the biggest cello concerto ever written,” Peled said. “It’s certainly one of the big three concertos that we have, and it’s always a delight to play.”

Next we talked about setting. “To better understand the piece, one has to place oneself in Paris — the Champs-Élysées, the Paris Conservatoire — at the end of the 19th century,” he said. “This was the center of the musical world, which had shifted from Vienna and would later on shift to New York. And it’s a place where Saint-Saëns (below) wanted to make a mark. He thought that through the cello, which nobody else was really writing for, he would be able to make that impression. And he certainly did.”

I was curious to ask Peled about one of his calling cards as a performer: putting on one-hour, informal recitals full of conversation with the audience. “I call it a performance chat,” he said. “It’s something I love doing because I feel that it shows in the best way who I am as an artist and as a human being, which go together.” Over the years, the program has evolved into a discussion of Peled’s life story, structured around the music that has shaped him.

“I feel very comfortable when I have the cello to hug and a microphone to talk,” he said. “That’s the best situation for me onstage. I never really plan what to say between pieces. I just want to feel the atmosphere and energy from the audience, and with that energy I take the performance and the story into a place where I feel they want it to go.”

The result is often a real dialogue. “I think people enjoy it more than just sitting there quietly as if stepping into a museum and listening to pieces that were written 200 years ago — which are beautiful,” he said. “It’s a different experience when they listen to those pieces while at the same time getting to know the artist behind the cello and behind the interpretation.”

If the orchestra allows it and if the hall isn’t too big, Peled will sometimes carry that style of performance over to a concerto setting. “I hope that in Cleveland I’ll have a chance to engage with the audience in that way,” he said, though he added that playing the Saint-Saëns is already a wonderful opportunity.

He looks forward to playing more and more of these types of concerts, as well as continuing to teach his students at the Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University about the art of speaking from the stage.

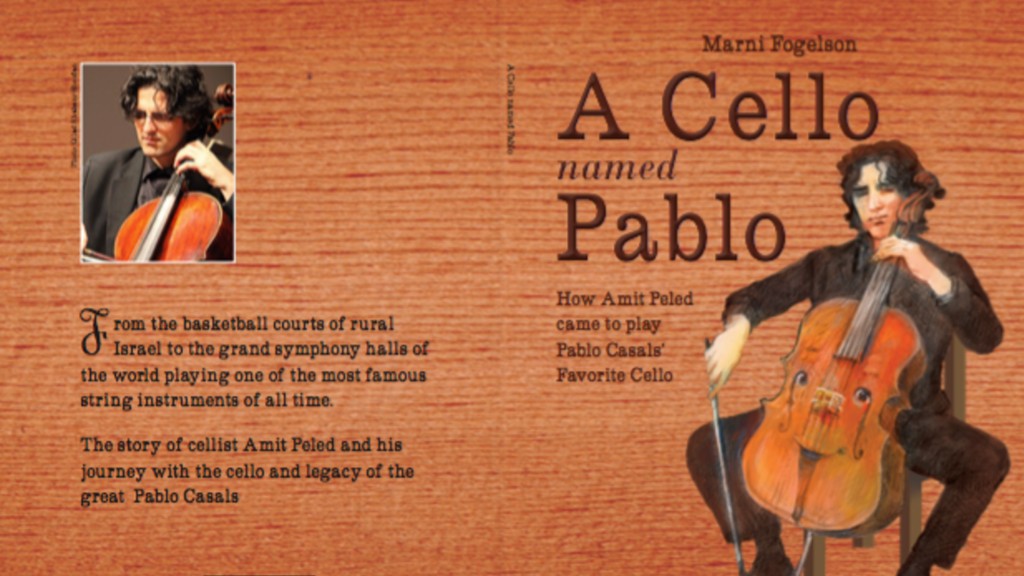

From 2012 through 2018, Peled performed on the Pablo Casals 1733 Goffriller cello, loaned to him by Casals’ widow, Marta Casals Istomin. He even published a children’s book — A Cello Named Pablo, written by Marni Fogelson and illustrated by Avi Katz — about the origins of that instrument and his own path to playing it.

Last December, he gave the cello back. “It was an amazing journey, but I felt that I needed to find my own voice and have my own instrument,” he told me. “Luckily, these days I’m able to play on a beautiful English cello by the maker Thomas Dodd. It was made in 1800, and what’s unique about it is that it’s in what we call mint condition.”

It arrived in the U.S. in the hands of a young girl emigrating from London to Cape Cod. She became an amateur cellist and kept the instrument “very comfortably in her living room all her life,” Peled said. “My mentor, the late great cellist Bernard Greenhouse of the Beaux Arts Trio, knew this lady. And once he was introduced to that cello, he didn’t leave the house until he wrote a check and she accepted it.” Peled played on that instrument when he began studying with Greenhouse in the ‘90s. “Later on I managed to buy it. Of course, I have to pay for it for the rest of my life, but it’s a magnificent cello, and I’m very privileged now to call it my own voice.”

You can visit YouTube to hear Peled read A Cello Named Pablo, which also touches on his early love of basketball. That interest never died. These days he’s a big fan of the NBA, particularly the Cavs.

Peled recounted coming to Cleveland for a playoff game. “It was an unbelievable atmosphere and an unbelievable feeling to see them win and advance,” he said. “And I’ll never forget it.”

These days, the Cavaliers press onward in what is called “rebuilding” mode, a difficult path characterized by incremental improvement and little immediate winning. “I hope they build up well,” Peled said. “And I kind of hope that David Blatt comes back now without LeBron and has a chance to really construct the team.”

One of Peled’s greatest joys at home is sitting down with his daughter, his two boys, and his wife to watch a game. “I only wish that during my week in Cleveland, the Cavaliers would have had an opportunity to be in the playoffs because I tell you, I would be there every evening if I could,” he said.

Peled signed off saying, “I’m really grateful for this opportunity to come to Cleveland and share the Saint-Saëns with the audience — and to play it five times, which is really rare. And I look forward to meeting everybody from the basketball world, from the music world, and from any world at our concerts.”

CityMusic Cleveland visits St. Noel Church in Willoughby Hills (Wednesday, May 15 at 7:30 pm), Temple Tifereth-Israel in Beachwood (Thursday, May 16 at 7:30 pm), Lakewood Congregational Church (Friday, May 17 at 7:30 pm), Shrine Church of St. Stanislaus in Slavic Village (Saturday, May 18 at 8:00 pm), and St. Jerome Church in Collinwood (Sunday, May 19 at 4:30 pm).

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 7, 2019.

Click here for a printable copy of this article