by Jarrett Hoffman

syn·cre·tism — the amalgamation or attempted amalgamation of different religions, cultures, or schools of thought (Oxford English Dictionary).

CityMusic Cleveland will explore that concept with an in-person concert of chamber music on Sunday, April 11 at 3:00 pm at Shrine Church of St. Stanislaus. (The audience will be limited to 250 people, and masks and social distancing are required. Click here to RSVP.)

The program begins with a quartet: Jungyoon Wie’s 2019 Han, played by violinists Miho Hashizume and Catherine Cosbey, violist Eric Wong, and cellist Sophie Benn. Then clarinetist Dan Gilbert will join the ensemble for Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s 1895 Clarinet Quintet in f-sharp.

On a purely musical level, it’s hard to pick two pieces that deserve a wider audience — one of them a fresh and riveting contemporary piece, the other a beautiful and unjustly neglected gem of the past. But these two composers also represent an intriguing pairing through the lens of syncretism.

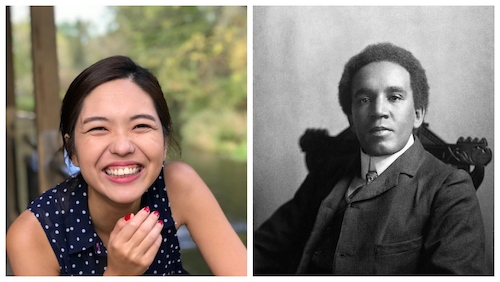

Born in Seoul, Jungyoon Wie (pictured above, left) came to the U.S. at age 16 to attend high school in Tennessee before studying composition at the College of Wooster and the University of Michigan. It was there that Wie wrote Han, her doctoral dissertation, in which she makes use of “Korean, folk, traditional, European, American, and contemporary expressive modalities,” she writes.

While Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (right) was born and died in Britain, he was multiracial — his mother a white woman from England, and his father a Black man from Sierra Leone. His growing fame as a composer led to three tours of the U.S. (where he was greeted by President Teddy Roosevelt). During that time, he became more and more interested in his heritage, including his father’s connection to America as a descendant of African American slaves, and sought to integrate elements of traditional African music into the classical sphere.

Even as early as age 17, Coleridge-Taylor showed a curiosity about music that blended cultures, inspired by Dvořák’s interest in African American and Native American music — Dvořák being a popular figure in Britain at the time. Indeed, although Coleridge-Taylor wrote his Clarinet Quintet in response to Brahms’ contribution to the genre, Dvořák is the clearer influence in the piece.

And while Hashizume hears the clarinet as a dominant figure in the Brahms Quintet, Coleridge-Taylor prefers to spread the wealth. “There’s more of a sense that everybody takes turns as a prominent voice,” she said. “It’s not like a prima donna with orchestra — it’s more conversational.”

The Coleridge-Taylor piece was a suggestion from Dan Gilbert, whereas Hashizume discovered Wie from a list of up-and-coming female composers that CityMusic executive director Eugenia Strauss recommended.

“Her piece was very fresh for me,” Hashizume said. “I don’t know what’s typical these days, but it’s not the contemporary piece that you imagine. She uses traditional Western writing combined with Korean traditions, so it appears very Korean, but it’s accessible to us. And she writes it in a really striking and organized way.”

Wie writes in her program note that the Korean term han centers around the idea of “impasse in one’s mind…a feeling of unresolved anger, grief, and regret that has been prolonged and accumulated over time. It has been identified that han, like trauma, suffers from its delayed manifestation which results in its ambivalent, paradoxical, and transgenerational quality.”

In a way, according to Hashizume, the five movements of the piece represent different stages of Wie’s journey dealing with trauma. In the first movement, we hear a traditional Korean tune with a complicated history that brings together both hope and grief. The second imitates the storytelling genre of pansori with its combination of singer and drummer, while the third is inspired by sanjo with its solo instrument accompanied by a Korean hourglass drum. The fourth represents the psychologically repressive element of han, and finally, through chant and meditation, the fifth aims to achieve a state of resolution.

“It’s kind of a theatrical piece — it takes you to different places — and I love that about it,” Hashizume said. “It has this depth and versatility of expression you can also find in other Korean art. I’m very intrigued by the range of expression in each movement.”

Photo from a short film featuring Wie’s Han, in performance by the Converge String Quartet and dancers Rie Kim and Jun Wakabayashi, filmed by Toko Shiiki

Drumming and vocalizing are not just starting points of inspiration from those genres mentioned above, but actual requirements in the piece — Hashizume, for one, will take up the janggu, that hourglass drum.

As any musician who has ever had to hum, snap their fingers, or stomp their feet in a piece of music — let alone sing or play another instrument entirely — it can be a challenge to pull things off convincingly. On that note, Hashizume had this to say about her colleagues:

“I couldn’t find better people to do this with. I have complete trust in them, and I’m very fortunate because singing and drumming in front of people — it takes guts. It makes you feel a little bit vulnerable. But those three, we’re comfortable with each other, and when we tried it for the first time playing as a group, it didn’t feel like the first time. So it’s wonderful that we’re together for this project — I’m very grateful for that.”

Having discussed identity together in relation to Coleridge-Taylor and Wie, in closing I shifted the spotlight over to Hashizume herself: as an Asian American woman, what’s it like to be playing a piece by an Asian American woman composer?

She began by recounting her experience at the recent Stop Asian Hate rally in downtown Cleveland. She was asked to perform for the event, and found herself struggling to think of classical pieces by Asian composers off the top of her head. “I feel very lucky to present this piece,” she said, adding that she and Wie have agreed to dedicate the performance to the victims of the Atlanta shootings last month.

Photo by Joshua Gunter, cleveland.com

It’s also important to note that Hashizume was raised in Japan, while Wie grew up in Korea, “so there are some similarities and some differences in our upbringing,” the violinist said. She went on to describe her longstanding interest in Korean culture, which has only grown since learning about this piece. She’s currently reading Korean-American writer (and Oberlin graduate) Cathy Park Hong’s nonfiction book Minor Feelings.

(To quote one passage from the book, “Minor feelings occur when American optimism is forced upon you, which contradicts your own racialized reality, thereby creating a static of cognitive dissonance…When minor feelings are finally externalized, they are interpreted as hostile, ungrateful, jealous, depressing, and belligerent, affects ascribed to racialized behavior that whites consider out of line. Our feelings are overreactions because our lived experiences of structural inequity are not commensurate with their deluded reality.”)

Moving back to Hashizume, her performance at the Stop Asian Hate rally didn’t quite pan out thanks to the rain, but she still found the event to be a powerful experience.

“It’s impressive that Cleveland did that,” she said. “They had the community that supported it and got together right away — that was incredible. It was nice to see that.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 7, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article