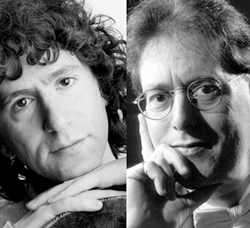

by Daniel Hathaway

Even that impressive level of authenticity might not perfectly suit these three sonatas. “Unlike the violin sonatas, the cello sonatas really span the entirety of Beethoven’s development as a composer,” Levin said in a telephone conversation from his home in Cambridge, MA, where he recently retired from the Harvard music faculty. “There are the two opus 5 sonatas from his early period, the great A-Major sonata, op. 69, from the middle period, and the visionary sonatas of op. 102 which inaugurate the late period.”

Levin feels that programming one sonata from each of those stages in the composer’s career will give the audience some idea of Beethoven’s evolution. “But in the most perfect of worlds, we’d use at least two different keyboard instruments,” Levin said, because the piano evolved along with the composer during Beethoven’s career. When he and Isserlis performed all five sonatas and the complete sets of variations in Salzburg, he had access to both a five-octave fortepiano (for opus 5) and a six-octave instrument (for op. 69 and 102). “But that’s a luxury that’s often rather difficult to achieve,” Levin said.

“In most cities, the logistics of finding two top-flight instruments of two different epochs is daunting. We had a number of adventures trying to find an instrument to import to Cleveland. We ended up with a six-octave instrument very kindly supplied by Malcom Bilson, and one of his students is driving it to Cleveland from Ithaca, NY. It’s going to be very nice, and because it’s an original and not a copy, it should be less fragile than a reproduction.”

Though they’ve known each other for years, Levin can’t recall when he and Isserlis first got together as performers. It might have been in 2004, and the subject was probably Beethoven. “We performed all the Beethoven cello works in two concerts at the Gardner Museum in Boston, as well as in England — once in Norwich and twice in London, at the South Bank and in Wigmore Hall. We also recorded the Beethoven Triple Concerto with Isabelle Faust and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Then there were a number of concerts running up to December of 2013, when we recorded the Beethoven cello works in London. After Cleveland, where we’re only doing a single program, we’ll play the two-concert set in Vancouver, and next fall in Ithaca. The recording won Gramophone’s recording-of-the-month when it came out in 2014. They liked it very much.”

It was Levin who originally convinced Isserlis to take on the Beethoven project. In a 2007 interview in The Guardian, the cellist confessed there was a time when he didn’t like the composer very much. “Once I had got over my rather pathetic little show of resistance to Beethoven, I started to programme the sonatas individually from time to time, but I shied away from playing the five together, as a series. It was only in 2004, when I was invited to perform them all in Boston with Robert Levin on the fortepiano, that I caved in. I found the prospect irresistible: Robert is not only a great player, but also a very distinguished musical scholar, and I knew I would learn a lot from working with him.

“Furthermore,” Isserlis continued, “he has access to some wonderful fortepianos, similar to the instruments Beethoven would have played himself. Performing the sonatas — especially the early ones — with a modern grand piano throws up all sorts of balance problems that would not have existed in Beethoven’s time; playing them with a fortepiano brings us much closer to the sound-world that he knew.”

“Playing Beethoven cello sonatas with standard instruments means that the piano has got to be constantly adjusting downward to preserve the balance,” Levin told me. “What’s extraordinary about using gut strings and period pianos is that there are no such strictures. The piano can play flat out. The volatility, the explosiveness, the intensity of the discourse is much, much more evident, and this is the reaction that listeners and critics have: the pieces become much more path-breaking for the fact that there are no limits of an artificial kind that are placed through the evolution of the instrument.”

To prove his point, Robert Levin ventured briefly into physics. “You go from 1800 kg of tension in a Mozart piano to maybe around 5000 kg in the late Beethoven period to around 20,000 kg in a concert grand with a cast-iron plate. That tension creates much more sustaining and the over-stringing creates much more concentration of the sound, but forces the pianist to select the most important voice and to subjugate the others. We’ve been told since we were children to ‘bring out the melody,’ which actually means ‘suppress the left hand.’ And this is what we do.

“It’s something we’re so used to that when Malcolm Bilson pointed this out to me some years ago, I thought he was exaggerating,” Levin said. “But I quickly became aware of the fact that he was not exaggerating at all. That’s simply an acoustical fact, and I often give lectures in which I point out how different the opening of the Beethoven ‘Waldstein’ sonata sounds on a period piano and on a concert grand. It’s something people can pick up on.

“I think that’s the thing the audience is going to be surprised at on Tuesday: that both of the instruments are capable of enormous power and enormous delicacy,” Levin said. “The ‘moderator,’ or so-called celeste stop on a period piano is a sonority to which there is no equivalent on the concert grand. It also has a shifting ‘soft’ pedal, but this is another matter. We can play enormously softly, but we can also play in the face.

I end our conversation by suggesting that the opus 5 sonata, more a piano sonata with cello than the other way around, must also be more enjoyable to play on the fortepiano. “It certainly is,” Levin said. “Having no holds barred is great fun!”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 9, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article