by Daniel Hathaway

As the Canadian-born violinist told us in a phone conversation last fall, he and his piano colleague once booked a studio in England to record a commissioned piece, but the work wasn’t ready yet. “The space, the recording engineer, and the producer were all on hold and we were faced with a whole day of dead time. What could we do to turn this into a useful day?”

Having performed Beethoven’s Ninth Sonata (the “Kreutzer”) quite frequently around that time, Ehnes proposed using that day to record it. “It’s never a bad idea to have a recording of the ‘Kreutzer,’ and we could figure out what to do with it later.”

What they did with it later was to record Beethoven’s Sixth Sonata and release the two sonatas on the same disc. “Some publications assumed that this was the start of a cycle,” Ehnes said, and that prediction came true when the violinist was looking for a way to mark the big anniversary of the composer’s birth in 2020.

On Tuesday, January 14 at 7:30 pm in the Maltz Performing Arts Center, Ehnes and Armstrong will play the “Kreutzer” to end the second of their three-concert cycle on the Cleveland Chamber Music Society Series. The program will begin with the F-Major Sonata, Op. 24 (“Spring”) and the A-Major Sonata, Op. 30, No. 1.

An interesting feature of the program is that the original finale of Op. 30, No. 1, a large-scale rondo of striking brilliance and difficulty, ended up as the finale of the “Kreutzer,” Beethoven having written a new theme and variations set for the third movement of the A-Major work.

The “Kreutzer,” ironically dedicated — second-hand — to a violinist who seems never to have performed the work, has become extra-musically famous for inspiring a novella by Tolstoy and a string quartet by Janáček. Its back story is fascinating, though versions differ in certain details.

Bridgetower made his debut in Paris in 1789. After giving concerts in Dresden in 1802, Bridgetower traveled to Vienna, where he met and impressed Beethoven. The composer decided to revise a recently-composed violin sonata and perform it with him. The piece received its debut on May 24 of 1803 at the bracing hour of 8 am at one of Ignaz Schuppanzigh’s morning concerts in the Augartensaal, attended by the British Ambassador, dukes, and princes.

According to one account, Beethoven finished his revisions at 4:30 that morning, leaving no time to copy the score, much less rehearse the piece. Depending on the source, Bridgetower either read the whole work off the score over the composer’s shoulder, or did that just for the second movement.

Apparently the violinist had an epic case of sang-froid, Beethoven’s handwriting being notoriously difficult to decipher. According to one account, Bridgetower even improvised a virtuosic response to a huge piano run in the first movement that inspired Beethoven to interrupt the performance to embrace him.

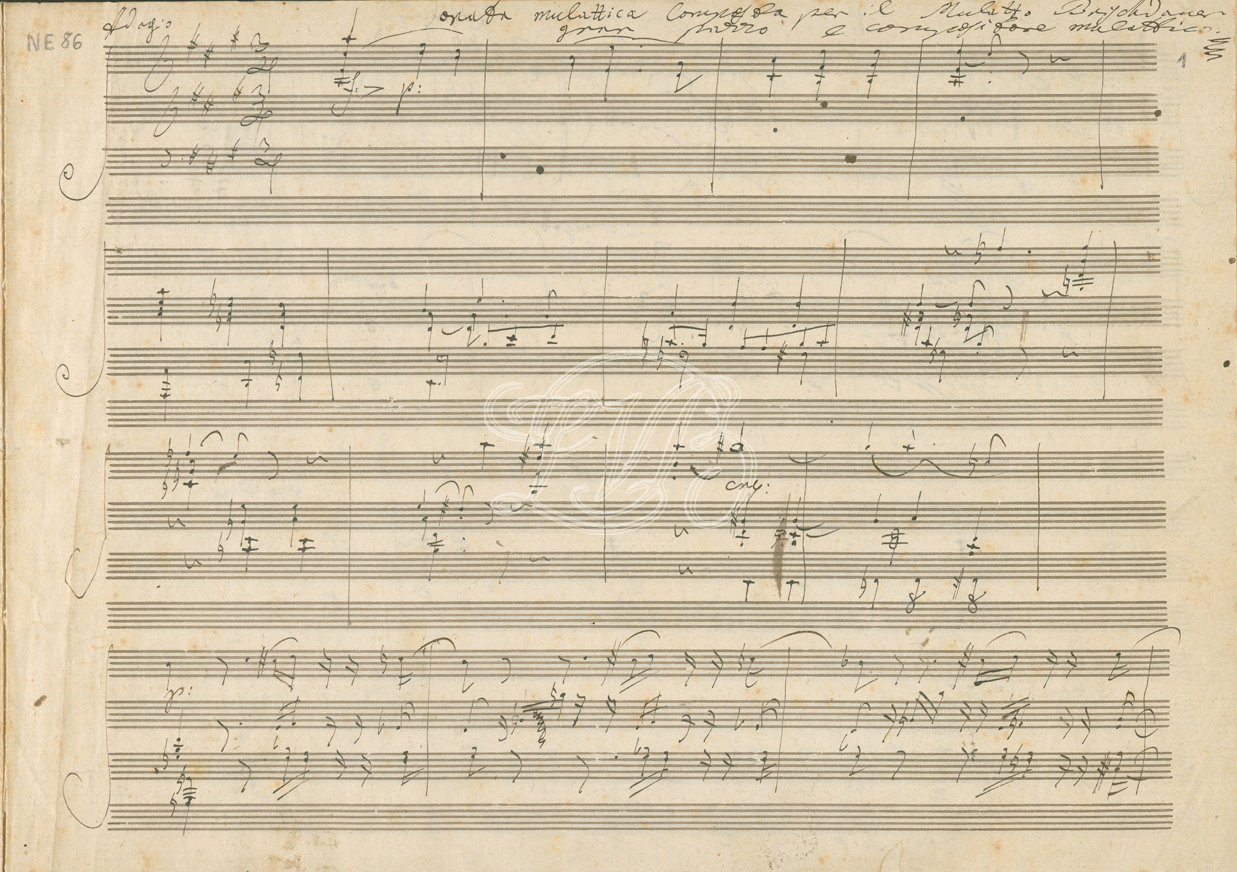

Afterwards, the composer dedicated the sonata to Bridgetower, writing across the top of the score the good-natured message, “Sonata per uno mulaticco lunattico” (Sonata for a lunatic mulatto).

op. 47

How did the Sonata not become known as the “Bridgetower”? The friendship went sour when Bridgetower apparently made a disparaging remark about a woman Beethoven admired. When the composer published the Sonata in 1805, much like his sudden cancellation of the dedication of his third symphony to Napoleon, he changed the dedicatee to Rudolphe Kreutzer, the French violin virtuoso, who he may never have met, and who disliked the work and seems never to have played it.

What happened to Bridgetower, who along with Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de St. Georges, and Ira Aldridge, were celebrated Afro-European musical celebrities of the era? He settled in London, was elected to the Royal Society of Musicians in 1807, earned a Cambridge degree in 1811, was taken under the wing of the British Prince Regent (soon to become King George IV), and married in 1816. He lived until 1860.

At the end of his life, one account has Bridgetower dying in poverty in a home for the destitute in Peckham, while another has him leaving an estate of £1,000 to his sister-in-law. You can visit his grave in Kensal Green Cemetery — or keep his memory alive by thinking of him every time you hear Beethoven’s Opus 47.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 11, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article