by Daniel Hathaway

His agenda is his specialty: Baroque music, which he characterizes in his remarks as “over the top, what I like in music. It’s as if you take the front of the Supreme Court Building — very symmetrical, nice columns — and put all the frou-frou of fancy violin parts on top of the rough and tumble and fun part of the music.” Comparing it to jazz, he notes “in this music you have to do a lot of it for yourself.”

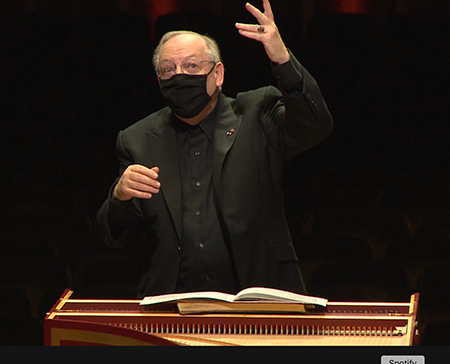

Not one to completely rearrange the furniture when he guest conducts, McGegan allows his players to retain their robust sonorities — and a certain amount of vibrato — while infusing his performances with Baroque contrapuntal clarity. The Handel selections, using strings only during this period when oboes, bassoons and other aerosol-producing winds are sidelined, sound rich but malleable. The Corelli, a concerto grosso which features violinists Peter Otto and Stephen Rose and cellist Mark Kosower, is replete with virtuosic charm.

“Nine soloists,” McGegan goes on. “Wherever do you get that?” In this case, from the front ranks of The Cleveland Orchestra string sections, which results in a stellar ensemble including violinists Peter Otto, Amy Lee, and Stephen Rose, violists Wesley Collins, Lynne Ramsey, and Lembi Veskimets, and cellists Mark Kosower, Richard Weiss, and Charles Bernard, with bassist Max Dimoff underpinning them on continuo. Quick camera cuts between players underline the soloistic give and take of the energetic outer movements.

The piece is obviously the work of a precocious young musician who has his ears full of everything he’s recently heard, and wants to incorporate that into his own writing. The first movement begins with Baroque gestures. The second, charmingly marked “Andante amorevole,” begins with only the upper strings. The Menuetto is a catalogue of sequences and motives built on triads. And given the last movement’s sudden tendency to break out into fugues, you can imagine that Mendelssohn was captivated by the finale to the “Jupiter” Symphony.

McGegan notes that the strings-only piece makes a wonderful virtue out of the current necessity for social distancing. It also makes a fine conclusion to the fourth episode of The Cleveland Orchestra’s In Focus series, the fifth to come in January.

Photos: Roger Mastroianni.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 14, 2020

Click here for a printable copy of this article