by Daniel Hathaway

On June 25, 1910, Gabriel Pierné conducted the premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s The Firebird at the Paris Opéra. Barely a year later, on June 8, 1911, Pierre Monteaux raised his baton for the first performance of Stravinsky’s Petrushka at the Théâtre du Châtelet, and the famous, chaotic debut of Stravinsky’s Le sacre du printemps followed under Monteaux at the Théâtre du Châtelet on May 29, 1913.

Tucked in between Petrushka and Sacre, on June 18, 1912, came the premiere of Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé, completing four straight years of landmark events in the world of dance.

Ravel’s “symphonie choréographique” is most often presented today as an orchestral work and usually in the guise of the two suites the composer later extracted from the full score. But when Franz Welser-Möst and The Cleveland Orchestra return to the Severance Hall stage this Thursday with the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus for three weekend concerts, patrons can look forward to hearing Daphnis et Chloé in all its 55-minute-long sonic splendor, in a program that also includes Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony.

For Daphnis, Fokine distilled and vastly simplified the plot of the sole surviving work of the same name by the 4th century Greek poet, Longus. The poem is a pastoral idyll chronicling the love affair between a goatherd and a shepherdess. The plot is complicated by a triangle involving the cowherd Dorcon, the abduction of Chloé by a band of pirates, and her rescue by Pan’s nymphs. The lovers are reunited as dawn breaks, and the story ends with general rejoicing.

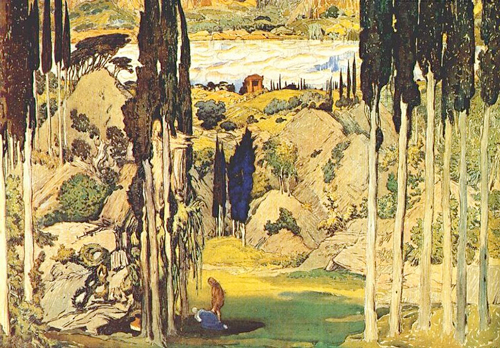

In addition to Diaghilev, Fokine and Ravel, the production team included the scenic designer Léon Bakst (set design pictured below).

Though conceived as early as 1909, the ballet would experience a long gestation, due not only to the composer’s meticulous work habits but also to the challenges of collaboration. Quite early on, Ravel bared his frustrations about creating a ballet by committee. In a letter dated in June of that year, he wrote, “I’ve had a really insane week: preparation of a ballet libretto for the next Russian season. Almost every night, work until 3 a.m. What particularly complicates matters is that Fokine doesn’t know a word of French, and I only know how to swear in Russian. Even with interpreters around, you can imagine how chaotic our meetings are.”

Disagreements about the concept were inevitable. Ravel wrote, “My intention in writing the ballet was to compose a vast musical fresco, less concerned with archaism than with faithfulness to the Greece of my dreams, which is similar to that imagined and depicted by French artists at the end of the eighteenth century.” Fokine, on the other hand, was just fine with archaism, having based his choreographic concepts on the illustrations on Greek vases.

Though Fokine noted later that he and Ravel had only one disagreement — how to depict the pirate attack — Ravel was permanently affected by the collaboration. Before undertaking his next ballet score, he wrote to the head of the presenting theater, “I would prefer to write the libretto myself, with some guidance. The precedent of Daphnis et Chloé, whose libretto was a source of perpetual conflict, has made me extremely reluctant to undertake a similar experience again.”

Finally, in 1911, Ravel seems to have thrown up his hands just as he arrived at the final scene of Daphnis. He asked the composer and pianist Louis Aubert, who premiered his Valses nobles et sentimentales that same year, to finish the ballet, offering to give him full credit for the work. Aubert turned him down, later writing, “The greatest service I ever gave music was convincing the great Ravel that he should finish his greatest work. In that respect, I am a great composer.”

Even after it moved from the theater to join the canon of great orchestral works of the twentieth century, Ravel’s colorful and evocative score had to wait a while before technology would allow music lovers to enjoy Daphnis et Chloé at home. Recording engineers could slice and dice other composers’ music to fit on a series of 78 rpm discs, but Ravel’s continuous music traced a longer arc and resisted that kind of treatment. With the arrival of the LP era, Daphnis finally acquired a suitable medium, and among the first conductors to record the whole ballet was none other than the 84-year-old Pierre Monteaux. His 1959 recording with the London Symphony and the chorus of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden came nearly fifty years after he had conducted its premiere in Paris.

Ballet fans who would like to experience Daphnis complete with dance (choreographed by Frederick Ashton) can access the Royal Ballet’s performance via YouTube.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 6, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article