by Mike Telin

The program will include chamber works by Zamecnik and his mentor, Antonín Dvořák, performed by violinists Isabel Trautwein, Alicia Koelz, and Katherine Bormann, violist Eric Wong, cellist Tanya Ell, clarinetist Robert Woolfrey, and pianist Rodney Sauer, who is also the director of the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, and who will deliver remarks on Sunday. Click here for tickets and here to read the previous article in this series, an overview of the Festival. A complete list of events and ticket information can be found at the end of this article.

In addition to selected movements from Zamecnik’s String Quartette in B-flat and Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello, the concert will include three of the composer’s Photoplay Scenes: Ode to Spring (1923), A Gruesome Tale (1922), and Bon Vivant (1917).

During the silent film era, John Stepan Zamecnik was perhaps the leading composer of photoplay music. If you have never heard of photoplay music, you’re not alone. “It was a term that was used at the time, although I think it was more of a sales thing,” Daniel Goldmark (pictured above), director of CWRU’s Center for Popular Music Studies, said during a telephone conversation. “If you asked most folks back then, nobody would have known what it was.”

Goldmark, who will speak during Sunday’s concert and who authored the article on Zamecnik for the online Grove Dictionary of Music, said that photoplay music was written to be used to accompany film before the advent of dedicated synchronized soundtracks.

Goldmark pointed out that Zamecnik grew up in Cleveland, went to Prague to study with Dvořák, came back, and immediately began working as a musician.

“He’s already composing by the turn of the century. He had a piece played by the Cleveland Symphony, which predated The Cleveland Orchestra by several years. He also went to work for Sam Fox Publishing — I think his first published piece with Fox was around 1907. The music industry saw a need and started selling music for the movies, and fortunately for us in Cleveland, one of the real pioneers in that field was Sam Fox. And he had the fortune of hiring Zamecnik early on.”

It wasn’t long before publishers began selling collections of music for silent film accompanists and music directors in theaters. “The earliest one that we know of is from 1909, and Sam Fox Movie Picture Music comes out a couple years later,” Goldmark said. “That’s also the first example of Zamecnik being tied to that world.”

Zamecnik was also an active member of the Hermit Club. “I remember being in Cleveland for a meeting back in 2004. I knew that Zamecnik had written some of their reviews, so I called them. They were super nice, gave me a tour, and showed me some archival material.”

Goldmark explained that the Hermit Club “reviews” were similar to the stage shows that were popular in New York City at the turn of the 20th century, “before what we now think of as Broadway came into existence.” The songs in the reviews, he added, were timely to a fault and very place-oriented.

“Like the Broadway reviews which featured a standard group of characters, the shows that Zamecnik wrote for were very much along the lines of ‘The Hermits go somewhere and hilarity ensues.’”

The first review Zamecnik participated in was Hermits in Hollywood in 1907. He also wrote music for Hermits In Dixie (1908), Hermits in Africa (1909), and Hermits at Happy Hollow (1910). “That one was so successful that it went on the road and ended up in Chicago. It was staged under a different name because there was no Hermits Club in Chicago. So they turned it into a stand-alone show called The Girl I Love, and his last was Hermits in Paris in 1912.”

By 1914 Zamecnik was busy writing photoplay music and other types of music, such as instrumental tunes and the musical parts of theme songs, including the theme for Wings, the 1927 Academy Award winner for Best Picture. He also wrote the theme for Fox Movietone News. “If anybody knows a piece by Zamecnik, it’s because it was used in theaters for a long time after he died.”

How long did the practice of using photoplay music last? “1909 is the earliest known collection and by 1930, if not before, it kind of just went away, because the studios were releasing films with synchronized soundtracks,” Goldmark said. “You no longer had to have a music director, an organist, or pianist at a theater making decisions about the music.”

What makes Zamecnik’s photoplay music stand apart from that of other composers? “I’m not sure I have an answer,” Goldmark said. “Photoplay music, I feel, has to do a very distinct job, but in a way that doesn’t call attention to itself. It has to establish setting, place, and mood. It is also not supposed to pull you out of the experience of watching the story of the film. And Zamecnik’s music always accomplishes those things.”

Although the composer’s influence on the music world far outlived him, Goldmark said it’s important to remember that he worked in an industry where “the point was for people not to realize the music was playing, let alone who had written it. So for a large part of his life Zamecnik functioned in obscurity, if not complete anonymity.”

February 13 at 3:00 pm at the Hermit Club: violinist Isabel Trautwein and other members of The Cleveland Orchestra join Rodney Sauer and the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra in a concert of chamber works by Zamecnik and his mentor, Antonín Dvorak. Click here for tickets.

February 15 at 7:30 pm at the Birenbaum: Short silent films accompanied live by Oberlin Conservatory students. The performance is free. Click here for more information.

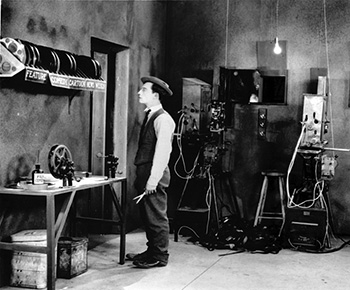

February 16 at 8:00 pm at the Apollo Theater: a screening of the Buster Keaton classic Steamboat Bill, Jr. accompanied by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra. The event is free. Click here for more information.

February 18 at 4:00 pm at Harkness Chapel: “Silent Film Scoring for Working Musicians.” Rodney Sauer, director of the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, discusses the art of putting music to classic films from the silent era with Daniel Goldmark, director of CWRU’s Center for Popular Music Studies. The event is free.

February 18 at 7:00 pm at the Cinematheque: Wings, the 1927 Academy Award winner for Best Picture with a soundtrack composed by Zamecnik. Click here for ticket information.

February 19 at 7:30 pm at the Cinematheque: The Wedding March, accompanied by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra. Click here for ticket information.

February 20 at 3:30 pm at the Cinematheque: Sunrise, accompanied by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra. Click here for ticket information.

Click here to access the Festival’s Facebook Page.

COVID protocols will be in place for all events. Proof of vaccinations/booster will be checked at the door and masks must be worn at all times.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 9, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article