by Daniel Hathaway

HAPPENING TODAY:

Another three-performance run that continues this evening pairs Cleveland’s No Exit with the St. Paul-based new music ensemble Zeitgeist for the second installment of No Exit’s Year of Surreality: The Unconscious. The 7 pm free program at Waterloo Arts includes films by composer/filmmakers James Praznik, Luke Haaksma, and Timothy Beyer, and multimedia works by Philip Blackburn, Joe Horton, and Kathy McTavish. (Repeated at 7 on Saturday at 7 at SPACES Gallery.

Two Oberlin events both happen at 7:30 this evening. A Brass Extravaganza features organist Jonathan Moyer in Warner Concert Hall (click here to watch remotely), and Gregory Ristow will lead the Oberlin Chamber Singers in a performance of David Lang’s the little match girl passion in Fairchild Chapel (click here for a live stream).

For details of this and other events, visit our Concert Listings.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

by Jarrett Hoffman

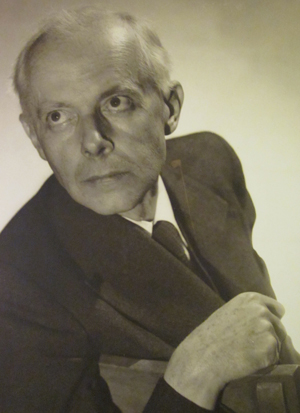

Birthdays on this date in music history fall more heavily on the side of pieces rather than people. Carl Nielsen’s Symphony No. 2 (1902), Sergei Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2 (1935), Béla Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra (1944), Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd (1951), and Leonard Bernstein’s Candide (1956) were all premiered on December 1.

One of a handful of works considered to be Bartók’s greatest, it is also perhaps his most popular. And it was held in high esteem from the start, although the composer did not live long enough to fully take in its legacy. He died of leukemia nine months after the premiere.

The success of the Concerto for Orchestra becomes even more meaningful when you take into account the situation of Bartók’s life at that time. Given the outbreak of World War II, the alliance between Germany and his native Hungary, and his anti-fascist views, Bartók fled to the U.S. in 1940, settling in New York City and becoming an American citizen not long before his death.

But he was not happy in America, his compositions little-known on these shores, and his health breaking down. It was while he was hospitalized (and not yet having received a diagnosis) when Koussevitzky came to visit him with the offer of the commission, which was to be in memory of the conductor’s late wife. Really it was a pair of Hungarian expatriates — violinist Joseph Szigeti and conductor Fritz Reiner — who were behind the idea.

Bartók accepted. After being sent by his doctor to Saranac Lake in upstate New York in July to recover from what was believed to be a recurrence of tuberculosis, he wrote the Concerto for Orchestra over the course of two months, completing it in October 1943.

Following the premiere at Symphony Hall in December of the following year, the composer wrote:

We went there for the rehearsals and performances — after having obtained the grudgingly granted permission of my doctor for this trip…. The performance was excellent. Koussevitzky says it is the ‘best orchestra piece of the last 25 years’ (including the works of his idol, Shostakovich!).

So, we end by expressing gratitude to the trio of Koussevitzky, Szigeti, and Reiner, for we may well have that commission to thank not only for the Concerto for Orchestra, but also for sparking inspiration for other late works such as the Sonata for Solo Violin and the Third Piano Concerto — all written in this otherwise dark period of the composer’s life.

Listen to a recording of the work from 1958 by Reiner and the Chicago Symphony here.