by Jarrett Hoffman

HAPPENING TODAY:

At noon, both in-person and live-streamed, enjoy a Trinity Brownbag “Organ and Brass Extravaganza” featuring organists Todd Wilson and Nicole Keller, and members of BlueWater Chamber Orchestra. Starting fifteen minutes later, over at Trinity Lutheran, organist Robert Myers gives “Praise and thanksgiving.” And at 7:30, CWRU Historical Performance faculty and friends, including cornettist Bruce Dickey, perform “Across the Alps.”

Details in our Concert Listings.

TWO ANGLES ON BIG CROWDS:

There is still plenty of uncertainty for cultural institutions at this point in the pandemic, including the willingness of audiences to return to in-person experiences. That question is magnified in San Francisco. “Arts groups are trying to gauge what the embrace of more flexible work-from-home policies will mean for their ability to draw audiences in a city whose housing crunch has already driven many people to settle far from downtown,” writes Adam Nagourney in The New York Times.

A more light-hearted question regarding large gatherings: did a group of El Sistema musicians — fingers crossed that it was more than 8,097 of them — break the world record for largest orchestra this past weekend? The Washington Post shares Regina Garcia Cano’s story for the Associated Press.

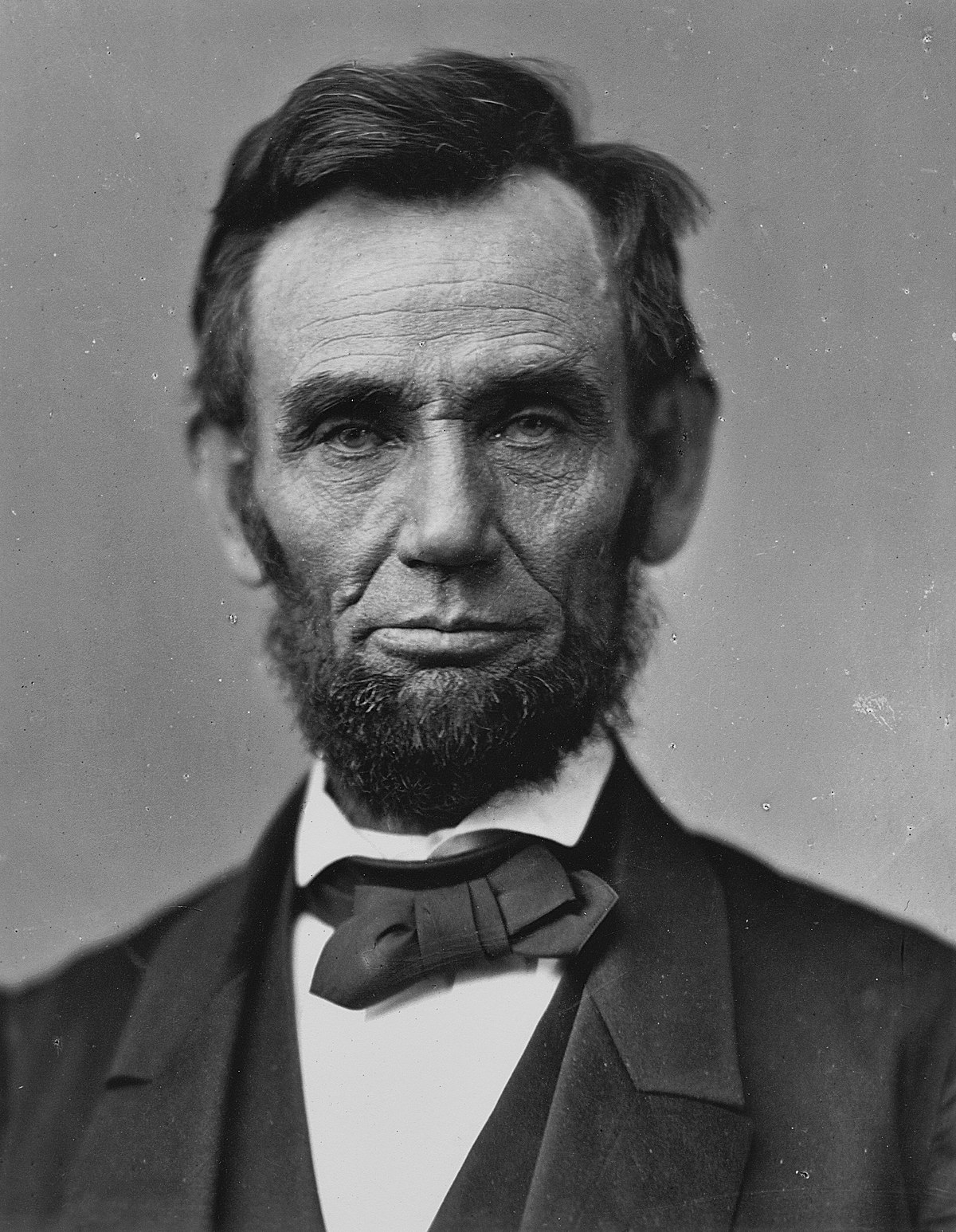

TODAY’S ALMANAC — LINCOLN IN GETTYSBURG:

According to some sources, Abraham Lincoln began his first draft of the Gettysburg Address on this date in 1863. He would go on to deliver that famous speech (“Four score and seven years ago…”) two days later during the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Of course, months earlier the city and its surroundings had been the site of the Battle of Gettysburg — a conflict horrific in its casualties but ultimately pivotal in the Union Army’s victory over the Confederacy in the Civil War.

Moving forward to the 20th century, two pieces of music referencing that president or that speech had their premieres on this date. We begin with Daniel Gregory Mason’s Lincoln Symphony, which was first heard at Carnegie Hall on November 17, 1937 in the hands of John Barbirolli and the New York Philharmonic.

In the opinion of Olin Downes, who reviewed the premiere for The New York Times, the more heavily programmatic movements were less successful, not to mention that “accents of other composers” such as Brahms, Franck, and Elgar made it feel not entirely fresh. However, he went on, a convincing and eloquent originality could be seen in the last movement, “where the suggestion is of mood rather than events or external characteristics…”

Listen to the symphony here (cued up to the finale) from Barbirolli and New York in a recording taken from airchecks, only intended for documentation.

The other premiere belongs to David Diamond (above), whose work This Sacred Ground — commemorating the centennial of the Gettysburg Address, and the first large-scale setting of the speech — was first performed on this date in 1963 by the Buffalo Schola Cantorum, the Fredonia Choir, the St. Paul’s Cathedral Boy Choir, bass-baritone George Hoffmann, the Buffalo Philharmonic, and conductor Lukas Foss.

Again The New York Times documented the premiere. Raymond Ericson described the work as “dignified and effective — a noncontroversial, useful piece for patriotic concerts.”

Perhaps its text setting deserves a special plaudit. In program notes for a recording by the Seattle Symphony, Steven Lowe writes, “It is always a challenge for a composer to set prose, rather than the customary poetry, in a song cycle, and Diamond’s imaginative setting balances the rhythmic freedom of recitative with the structured cadence of an aria.”

Click here to listen to that recording from Seattle. The orchestra is led by Gerard Schwarz, and is joined by the Seattle Symphony Chorale, the Seattle Girls’ Choir, the Northwest Boychoir, and baritone Erich Parce.

Back to Gettysburg and the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, it’s interesting to note that Lincoln’s address was not at all slated to be the main feature of the event.

That honor belonged to a man known at the time as a great orator, Edward Everett, who spoke for two hours (not atypical at similar events of the era) in delivering a 13,607-word speech. It was apparently impressive and polished.

According to one eyewitness, Lincoln spoke “with a manner serious almost to sadness.” He was also sick with what would soon be diagnosed as a minor case of smallpox. Wrote his assistant secretary John Hay, the president’s face had a “ghastly color,” and he was “sad, mournful, almost haggard.”

He needed only 271 words to enter into the annals of oration.