WEEKEND HIGHLIGHTS:

On Friday, October 10, the Miró Quartet (Daniel Ching & William Fedkenheuer, violins, John Largess, viola, and Joshua Gindele, cello) will continue its Complete Beethoven String Quartet Cycle celebrating the 30th anniversary of the quartet’s founding at Oberlin Conservatory. After the first two concerts on Thursday, the remaining nine quartets in this marathon will be performed over the weekend.

On Friday and Saturday at 7:30 at Severance Music Center, pianist Daniil Trifonov will join Franz Welser-Möst and The Cleveland Orchestra for performances of Johannes Brahms’ Second Concerto, and the Orchestra will fill out the program with Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 7.

And Henry Purcell’s popular 17th-century opera Dido and Aeneas will be staged simultaneously by two organizations:

Apollo’s Fire’s period instrument version led from the harpsichord by Jeannette Sorrell, will feature Aryssa Leigh Burrs, mezzo-soprano (Dido), Edward Vogel, baritone (Aeneas), Andréa Walker, soprano (Belinda), Cody Bowers, countertenor (Sorceress), and Apollo’s Singers at the Tudor Arms Hotel (Friday at 7:30), at the Cleveland Institute of Music (Saturday at 7:30) and in Gamble Auditorium at Baldwin Wallace (Sunday at 4).

Baldwin Wallace will present its take on Dido in “a reimagined telling set within the dystopian framework of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale” at The Helen in Playhouse Square on Friday at 8 pm, and Saturday at 3 pm and 8 pm.

For details of these and other classical events, visit the ClevelandClassical.com Concert Listings.

The Canton Repository has published a tribute to organist W. Robert Morrison on his 100th birthday. After eighty years as a church musician, 45 of them at Church of the Savior, as well as 35 at Temple Israel, he’s still active, now serving as music director at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church. Click here to read “At 100, Canton’s ‘Father of Church Music’ plays on at Canton church.”

WEEKEND ALMANAC:

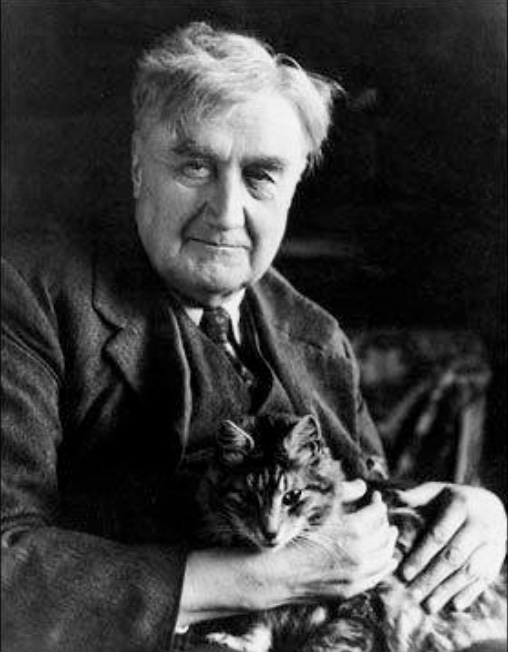

Writing in The Guardian, Hugh Morris reconsiders the works of Britain’s favorite composer in his anniversary year.

“When encountering an unfamiliar composition by Ralph Vaughan Williams, I find myself asking the same questions: where have I heard this before? Do I know this already or am I simply imagining it?

“Clear answers are offered by Eric Saylor’s groundbreaking biography, released to coincide with Vaughan Williams’s 150th birthday. Saylor approaches his subject with fresh ears and a host of thoroughly researched and well-rounded insights that look set to change the discourse surrounding the composer in his anniversary year.”

The range of RVW’s work was vast. Let’s suggest just two radically different compositions that reflect his lifelong interests.

The first represents his close association with English folksong, of which he collected numerous examples and made arrangements for various combinations of voices and instruments. He so internalized that repertoire that he could write easily in the style, as proved by his settings of Edwardian poet A.E. Housman’s verse in Along the Field, simply but eloquently scored for solo voice and violin. Listen here to a performance of the cycle by soprano Marie Henriett Reinhold and violinist Dietrich Reinhold.

The other extreme finds Vaughan Williams exploring the full range of drama at his disposal as an early 20th century composer. Orchestrally, this expresses itself in his symphonies and in such works as Job, a Masque for Dancing, with its frightening musical depictions of Satan, but otherwise in A Vision of Aeroplanes, his charmingly titled setting of the Vision of Ezekiel from the Hebrew scriptures for organ and chorus. The organ part is as fearsome for the keyboardist as the musical declamation is for the singers. Stay with it to the end in this performance by the University of Cambridge’s Clare College Choir.

Nearly everyone has a favorite high school English teacher, and mine was the late Martha Herrick, who deadened the blow of exams and quizzes by playing Vaughan Williams on her classroom phonograph at Topeka High School.

She was a true fan who once dreamed about watching RVW composing in his study. The vision was so detailed and compelling that she wrote about it in a letter to the composer’s widow, Ursula, whom she had never met. The reply — Martha had described her husband’s work habits perfectly although no one but the composer had ever entered his creative sanctuary — initiated a friendship renewed over tea in London in many subsequent years.