by Daniel Hathaway

On Friday, September 22 at 7:30 pm in Finney Chapel, the Emersons will play Felix Mendelssohn’s Quartet No. 2 in a, Sarah Kirkland Snider’s Drink the Wild Ayre, and Ludwig van Beethoven’s Quartet No. 13 in B-flat and Große Fuge. Tickets can be purchased online.

I caught up with violinist and Cleveland native Philip Setzer — both of whose parents were violinists in The Cleveland Orchestra — via Zoom to talk about the group’s four and a half decades on the road and its plans for this season’s grand finale.

Daniel Hathaway: I’m really pleased to have the opportunity to chat with you at the end of your long, distinguished run with the Emerson, having had a small part in launching your career by presenting the quartet on the Gund Concert Series at Groton School way back in 1976. We were looking for an exciting new ensemble of young musicians who would connect well with high school age students, and you were all fresh out of Juilliard and making waves by alternating first and second violins.

Philip Setzer: And here we are 47 years later and those kids are all like 60, right? Crazy, isn’t it? We’ve got quite a farewell season lined up.

DH: This won’t be quite like a never-ending Rolling Stones goodbye tour, right?

PS: Well, we’re not making that much money, that’s for sure. We feel like we’re still playing and getting along well, and you want to stop before somebody tells you you should have quit long before. We’re being followed on this tour by a crew who’re doing a documentary film about us, and hopefully somebody will find that interesting.

DH: I understand that the Quartet has played on the Oberlin Artist Recital Series four times before, beginning in 1985 when you played the same Beethoven quartet you’ll be performing on September 22.

PS: Yes. I’ve also occasionally done a master class at Oberlin, and I’ve served on the jury for the Cooper competition. The young woman who won that time was 13 years old, and now she just won first prize in the Tibor Varga competition in Europe at the ripe old age of 14. She’s really something special.

DH: What were we doing at 13 and 14?

PS: Well I had just finished my bar mitzvah but I wasn’t winning any competitions at that point, that’s for sure.

PS: It feels like Paul Watkins has just joined the quartet, but it’s already been 10 years, so there were pieces that he hadn’t had a chance to play very much with us, like the Mendelssohn Opus 13 Quartet — one of my very favorite pieces — so, we wanted to include that.

And because the final concert is going to be at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, which is run by David Finkel, our former cellist, and his wife Wu Han, who are the other members of my trio, I had thought about the possibility of playing the Schubert Two-Cello Quintet with David, but maybe it wouldn’t be fair to Paul to make him share the last concert with another cellist. Then Paul brought it up himself and said, well, why don’t we do the Schubert with David? So that was perfect. It makes sense because David was in the quartet for 34 years, and David and Paul have become very close friends. They live near each other in Westchester, and we’ll be rehearsing it at David’s house the week after next. The film crew will be there too, so that’ll be fun. And it’s a great piece, my absolute favorite.

Then of course we wanted to do a big Beethoven quartet to go with that so we picked Opus 130 with that cute little finale, the Große Fuge, so it’ll be quite a program. We’re playing the same program where we teach at Stony Brook University on Long Island the week before for our final concert. And then we’ll end the tour at Lincoln Center. It was originally just one concert, but that happily sold out very quickly, so we added a second.

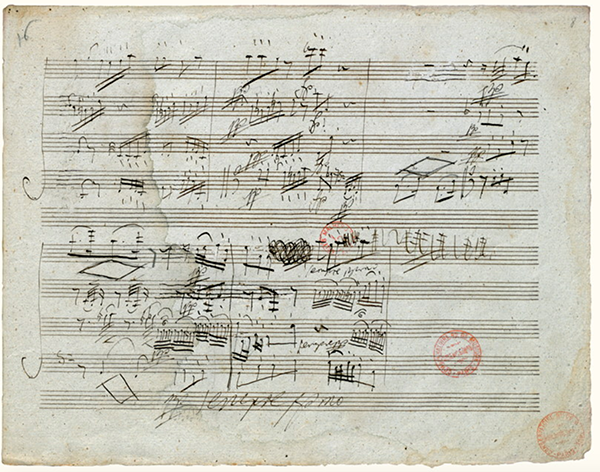

PS: On tour, the substitute finale works better, because the Große Fuge is exhausting, but I always feel that going from the otherworldly beauty of the Cavatina to the Fugue is like the jaws of hell opening. You fall in and then you claw your way out at the end. There’s just such an incredible drama to that. I can only imagine what the Große Fugue sounded like at the premiere. Probably not very good, but maybe it was just that people didn’t understand the music. Clearly, Beethoven himself had doubts about it, because he agreed to publish it separately, and then wrote an alternate finale, which is actually the very last piece that he composed.

DH: The Große fuge is strange enough when played by a quartet, but it’s really bizarre watching the whole Cleveland Orchestra string section play the piece.

PS: They opened with it in Paris on the very last concert that my parents played with the Orchestra. We had a quartet tour that started a few days later, so I went over early and surprised them with some help from friends in the orchestra who got me tickets. It was all kept very secret, and I sat up in the balcony with my program in front of my face so they wouldn’t see me.

After intermission, they played Beethoven 7, whose last movement is one of the most joyous pieces Beethoven ever wrote, but I’m sitting there thinking that this is the last time my dad’s going to turn the page. Tears are rolling down my face, and this woman next to me keeps looking at me like, what’s wrong with you? This is happy music. When it finally ended, she leaned over and asked, are you all right? And I said, yeah, it’s just my parents’ last concert with the orchestra. And she says, omigod, you’re Philip! It was Robert Shaw’s wife. Shaw was sitting two seats from me and we didn’t recognize each other and so that was kind of crazy. He happened to be in Paris too and knew that it was my parents’ last concert in the orchestra.

DH: On your Oberlin program, in addition to the Mendelssohn and Beethoven works, you’ll also be playing a piece by Sarah Kirkland Snider.

PS: I first met Sarah and heard her music at the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival in Detroit, where Paul Watkins, our cellist, is the artistic director. I liked her music a lot, and I got to know her a little bit personally. When we were looking for a short work to fit between the Mendelssohn and the Beethoven, we commissioned her to write one. We’ve been playing Drink the Wild Ayr quite often and people really love it.

It has great beauty and color and complexity in it. You know how you look at something like the inner workings of an old watch, a very finely made machine that’s actually just beautiful to see? That’s kind of how I feel about this piece. There’s a lot of intricate motion going on, very beautiful colors, and some really nice solos for each of us. And I would say it has kind of a gripping atmosphere. It’s dramatic in a certain way, and beautiful things are happening and bouncing off of each other. I like playing it very much.

DH: Well, you all have a terrific legacy to leave to the music world. What would be some of the high points looking back over those 47 years?

PS: Of course there were important concerts that helped us move along — like the first time we played all six of the Bartók quartets in one concert in New York, which was a crazy idea of mine. I was sitting home wondering how we should program them, because everybody was going to do that in 1981 for the 100th anniversary of Bartók’s birth. Then I saw the leatherbound red book of Bartók quartet scores and the idea just clicked of looking at them as a book, a kind of autobiography of his life. So I put the recordings on and listened straight through from the beginning to the end and I really felt like it worked on an emotional, historical, and artistic level. Some people thought it was gimmicky, but then when they came and heard it, they were really moved by it. So that was our first big performance like that, and it kind of launched us.

I think also that the two theater collaborations that we did about Shostakovich were very important — The Noise of Time with Simon McBurney’s Teatro Complicité, and then the more recent one that we did, Shostakovich and the Black Monk, with James Glossman directing and a number of wonderful actors. That was really experimental, and I think we gained a lot from that experience. There were a lot of musicians there who wouldn’t necessarily go to an experimental theater production, and there were a lot of fans of the actors and Simon McBurney’s company who came to experience the theater, but then really got into the quartet part of it.

Then there was our first Beethoven cycle, our first Shostakovich cycle, and of course the Bartók I mentioned. We’ve also had a lot of very good experiences with new music and working with the great composers who wrote music for us. The excitement of premiering something brand new was always wonderful.

DH: Cleveland has become kind of a hotbed of chamber music these days. And there are new string quartets being launched all the time.

PS: I’m very much involved in that. I teach at the Cleveland Institute, and I’ll be the Artistic Director of Strings Chamber Music starting this year. So I see so many young, wonderful groups coming from there, and from where my quartet is continuing at Stony Brook University with our Quartet Institute there. But it’s amazing just the number of really excellent young players and string players who really want to play chamber music.

You learn a lot about your own playing, too, because in a quartet, you have three teachers constantly telling you what they think you should do. You also become one of those teachers, and you learn a lot about how to suggest something — how to get your way but in a nice way.

DH: The Emerson certainly enjoy some of the most cordial relationships among its players.

PS: I think so.

DH: And when David left, he didn’t fall far from the tree.

PS: We were extremely lucky that the changes we had when David decided to leave were all very cordial. I remember asking him, who do you think could replace you? He said, well, my first choice would be Paul Watkins but you’ll never get him. You know, there’s also a nice connection with Paul and Cleveland because he’s married to Jennifer Laredo, Jamie’s daughter. So his in-laws, Jamie and Sharon, live in Cleveland and teach at the Institute. That’s kind of a nice connection.

DH: What advice would you give to a young quartet to have a happy life?

PS: They have to find their own way. Every group of people is different. All I can say is that there were a couple of agreements that we made early on that I think worked well for us over these many years.

One was that we tried to take the music very seriously, but not ourselves too seriously. We also tried not to talk too much in rehearsals. In the amount of time that you try to decide how you’re going to do something, you could have tried it 10 different ways and come up with probably a better way than any single person could think of.

The other two things I would say very quickly is we had a voting system that worked. It wasn’t democratic. We had to agree unilaterally and it had to be a consensus. If one person said no, that was the end of the discussion. In other words, each of us had a veto power, and I think that really helped make it work.

DH: Phil, thank you so much for taking the time to chat.

PS: I should mention that we’re also performing at Severance Hall on October 15 in a concert we’ve been trying to schedule for some time. We’re playing Beethoven’s Opus 131, Simone Dinnerstein is playing Philip Glass’s etude for solo piano, then on the second half we’re performing André Previn’s final work called Penelope for voice, singing voice, narrator, string quartet, and piano featuring Renée Fleming, Merle Dandridge, Simone, and the Emerson Quartet.

DH: Of course, we now know that venue as the Severance Music Center.

PS: I spent every week of my life there from the age of five until I left to go to Juilliard, sitting in row C in the dress circle. There were so many great, great performances I got to hear.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com September 14, 2023

Click here for a printable copy of this article