by Daniel Hathaway

Key was author of the poem Defence of Fort M’Henry, inspired by the British bombardment in Baltimore Harbor in September 1814, that became the text of The Star-Spangled Banner. Joined to a tune by British composer John Stafford Smith, the song was officially adopted by the U.S. Navy in 1889 and became our National Anthem by resolution of Congress in 1931.

The problem with Francis Scott Key, a Baltimore lawyer and district attorney, is that he had owned slaves since 1800. While he went on public record to oppose human trafficking, he also represented the owners of runaway slaves.

The problem with his poem is that for 21st-century America, its sentiments seem less and less conducive to uniting a divided nation.

The “Star-Spangled Banner” refers to the mammoth flag (originally measuring 30 by 42 feet) with fifteen stars and stripes symbolizing the states that formed the Union at the time. Raised “by dawn’s early light,” the flag, now owned by the Smithsonian Institution, offered proof of an American victory over the British during the War of 1812.

Fittingly for the occasion that inspired it, Key’s poem begins with military imagery. Those lines about “rockets’ red glare” and “bombs bursting in air” probably came to many people’s minds over the most recent Independence Day weekend as private fireworks detonated far into the night — more than making up for the cancellation of public celebrations.

The other three stanzas — the ones few people know and nobody sings — are problematic. The third makes ambiguous references to “the hireling and slave.” The fourth brings the Deity into play to bestow special favors.

Even Key’s contemporaries had issues with his text. Abolitionists mocked its refrain, suggesting that it should read “Land of the Free and Home of the Oppressed.” Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., though himself an anti-abolitionist, was moved to pen a fifth stanza at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861 to update its sentiments:

When our land is illumined with Liberty’s smile,

If a foe from within strike a blow at her glory,

Down, down with the traitor that dares to defile

The flag of her stars and the page of her story!

By the millions unchained, who our birthright have gained,

We will keep her bright blazon forever unstained!

And the Star-Spangled Banner in triumph shall wave

While the land of the free is the home of the brave.

And what about the music? Many national anthems and hymns are set to borrowed tunes, and the official anthem of the United States is no exception. It appropriates a British glee composed by the son of a cathedral organist for the Anacreontic Society, an exclusive London Men’s Club. Its members seem to have had little trouble negotiating the famously wide range of the tune — especially when lubricated by the fruit of Bacchus’s vine, as the refrain goes. Performed by a band, the music can take on a nobility it lacks when stylized by pop singers at modern sporting events. But is this the best we can do for a national anthem?

It’s as easy to topple a musical monument as it is to haul down a statue, but what do you put on that empty pedestal in its place?

Lift Every Voice and Sing has been proposed. Originally a poem by James Weldon Johnson, it was written to be recited by 500 school children in Jacksonville, Florida on February 12, 1900 in celebration of Lincoln’s Birthday. Five years later, John Rosamond Johnson, the poet’s brother, set it to a noble tune. Because it’s become America’s “Black National Anthem,” it should be off-limits to appropriation.

Columbia the Gem of the Ocean, an early alternative to The Star-Spangled Banner, shares a tune with a British song, Britannia, the Pride of the Ocean, but it’s unclear which came first. America (“My Country, ‘Tis of Thee”) also shares a tune with a British song, the National Anthem God Save the Queen (or King). An abolitionist version sarcastically includes the phrases “Stronghold of slavery, of thee I sing,” and “Where all men are born free, if white’s their skin.” Shouldn’t America’s National Anthem be home-grown and unique?

Then there’s America the Beautiful. Popular both for its words (by Katharine Lee Bates, a Wellesley College professor inspired by a visit to Colorado) and its music (the tune “Materna,” written by Episcopal organist Samuel A. Ward), it can seem a bit too hymn-like and its words hint at the doctrine of Manifest Destiny.

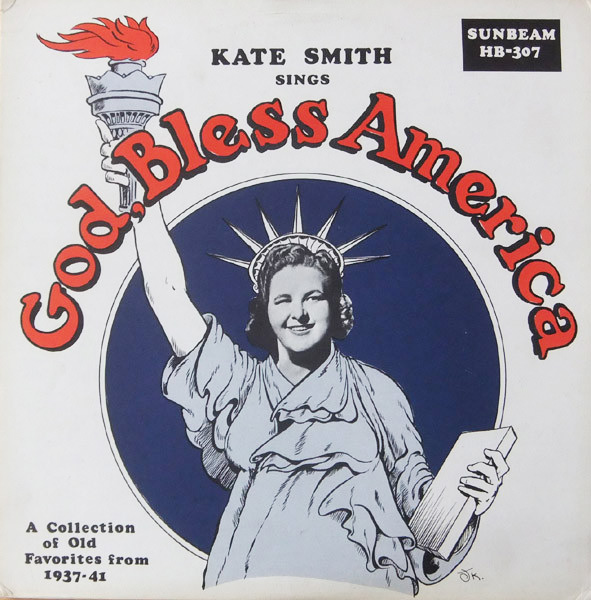

God Bless America was penned by Russian-born immigrant Irving Berlin as a World War I song, but it really belongs to Kate Smith, who popularized it during the Second World War. It’s rousing in a Broadway style, but some have criticized the words for advancing the idea of American exceptionalism.

From the same era, George M. Cohan’s 1906 You’re a Grand Old Flag has become a much-played marching song, but just imagine singing some of its lyrics:

Any tune like “Yankee Doodle”

Simply sets me off my noodle,

It’s that patriotic something that no one can understand.

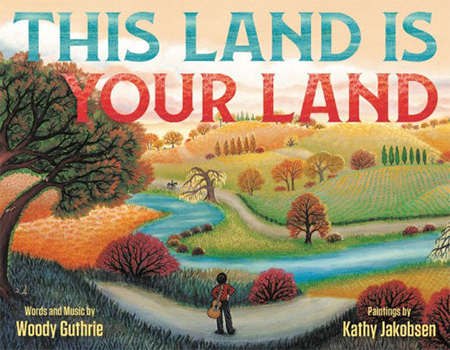

Woody Guthrie’s This Land is Your Land has been proposed by many. The folk singer wrote it after growing tired of hearing Kate Smith’s anthem (see above), so Guthrie’s original refrain parodied that song with “God blessed America for me.” It’s a great singalong piece, but along with many pop songs that find their way into National Anthem replacement lists, doesn’t really have the gravitas an anthem needs for state occasions. John Lennon’s Imagine — a much-suggested candidate — has wonderful lyrics, but doesn’t lend itself to mass singing.

In the end, it’s difficult to topple a monument like The Star-Spangled Banner without a worthy successor, and one that will please all of the country’s diverse constituents.

In 1992 the organization Anthem! America issued a call for composers and poets to come up with a new national song. The winner seems to have been America, My America, with words by two Tennessee poets inspired by the view from the Northern Rim of the Grand Canyon, and music by an Indiana teacher. A vigorous campaign to promote the winning anthem and nine runners-up came to nought, and it’s difficult now to find any specific references to the results on the Internet. Could this song performed by the U.S. Air Force Band have been that winner?

Perhaps it’s time to try again, or to commission a new anthem from several of our outstanding poets and composers, and do a runoff.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com July 8, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article