by Jarrett Hoffman

Premiering on February 1, last week’s episode of Les Délices’ SalonEra series explored “Afro-Caribbean Roots” in early music, delving into the evolution of an 18th-century Haitian text, the original works and arrangements of Guadeloupe-born composer Joseph Bologne, and the modinhas of Brazilian guitarist and singer-songwriter Joaquim Manoel da Câmara.

The first featured guest artist was Haitian baritone Jean Bernard Cerin, tuning in from Lincoln, PA. Cerin discovered Lisette, quitté la plaine, a text from his home country, after being inspired to find an intersection between his own background and his artistic practice in early music.

“My search has brought me to the earliest iteration of what became Haitian Creole, which is the Creole of Saint Domingue — a poem written by an 18th-century Caucasian colonial,” Cerin told Les Délices director and oboist Debra Nagy.

One thing that fascinates Cerin about the text is its unique take on slave narratives of the time period. “We have a humanization of this person who wants to have agency,” he said, noting that it seems fitting with the history of Haiti, “the first slave nation to receive its freedom.”

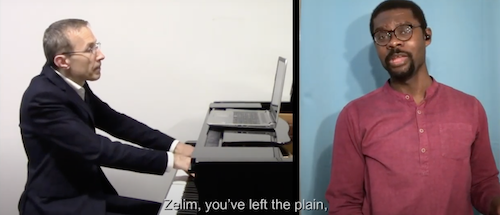

Several composers have set the text to music, and we heard two versions in this episode. The first (pictured above) featured a tune by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, elegantly arranged by Nagy to create “a salon performance that might’ve been heard in the 1740s or ‘50s in France, when Rousseau published this text,” she explained.

Over the continuo playing of Eric Milnes (keyboard) and Mélisande Corriveau (cello), Nagy and Cerin traded off melodies before combining beautifully in the end. Another striking moment came in one of the middle verses, whose slow tempo matched the deflated mood of the text as the speaker wastes away, his love having left for the city.

The three instrumentalists played with a wonderful sense of rhetoric and a beautiful tone throughout, and Cerin impressed with his clear and warm baritone and his obvious affinity for the text, acting it out engagingly both in his visage and his voice.

The conversation continued on the topic of the text’s migration, including its arrival in a collection of folk songs from New Orleans, collected by Clara Gottschalk. As Nagy noted, Gottschalk had been inspired by Dvořák’s interest in folk songs of the Americas. “So it’s not just a song collection,” the oboist said. “She presents it as a piece of ethnomusicology and a kind of legacy of Creole song from Louisiana.”

That setting, performed here by Cerin and pianist Martin Nerón, is quite different — more formal, like art song. It even has a different name: Zélim to quitté la plaine. “It sounds very French,” Cerin said, “however I have not located an original French tune, so right now we understand it as a Louisiana folk song.”

By way of the Haitian revolution — “Bologne might have been in Haiti in the early 1790s,” Nagy said — the episode transitioned over to that figure, perhaps the most famous composer with Afro-Caribbean roots. Earlier in the episode, Nagy gave a brief summary of Bologne’s life, from his fairly privileged background to his dual careers in music and the military, including how racism hampered both of those pursuits and his life in general.

One key focus of conversation among Nagy, Cerin, and soprano Sherezade Panthaki (connecting from New Haven, CT) was the challenge involved in tracing Bologne’s music, since some collections of songs that bear his name are very likely his arrangements of works by other composers.

The musical selections began with a piece definitely from his pen: the “Aria con variatione” from his Sonata No. 2 in B-flat, played as a single-person duet by violinist Allison Monroe. Her performance — a clip originally seen in SalonEra Episode Two — was keenly felt and keenly phrased through all of the composer’s clever and beautifully crafted variations.

Next came the “Jouissés de l’allegresse” from Bologne’s opera ballet L’amant anonime. Over the characterful underpinning of fortepianist Henry Lebedinsky, Panthaki showed off her wonderfully ringing voice, a beautiful vibrato she knows just when to use, and a delightfully paced cadenza — after which the duo smoothly reconnected, no easy feat in a virtual performance like this one.

Moving on to the book that holds several of what seem to be Bologne’s arrangements, Lebedinsky joined the discussion, comparing that volume to the notebooks of Anna Magdalena Bach. “Part of the value of these books is that the compiler saw these pieces as valuable enough that he or she took the time to put them together for patrons and friends,” the keyboardist said. “This is a window into the music of the time through the eyes of these master musicians.”

One such selection is the “Romance,” likely from the opera Rosine by Gossec, and arranged by Bologne in the performance heard here by Lebedinsky and Cerin, which featured an expressive introduction and beautiful transitions from minor to major and back again. Another arrangement in the hands of that duo actually served as a musical introduction to the whole episode: Dans la sabot perdu by Pierre Yves Barré. More up in the air in terms of origin is the Charmante fleur, which reunited Lebedinsky and Panthaki, and which “may or may not be by Bologne,” Nagy said.

The final third of the episode focused on guitarist Joaquim Manoel da Câmara, whose music was brought to the SalonEra table by Lebedinsky. “Very little is known about him,” the keyboardist said from Seattle. “He was a blind, mixed-race guitar player who spent most of his life in Rio de Janeiro. He would sit on the street corner and sing his songs.”

That’s how Austrian musician Sigismund Neukomm, who was working in Rio around 1810, came to know this music. “This is one of those moments that goes down in music history,” Lebedinsky said, “like Antonín Dvořák listening to Harry Burleigh sing spirituals and demanding that he write them down. Neukomm copied down twenty of these songs, and they survive in only one source, a manuscript in the National Library of France.”

Lebedinsky noted the influence of colonialism in much of Western music, including in the works of da Câmara, who mixed the style of Portuguese popular love songs with the melodic contours of Brazilian music. That blending of cultures is “one of the only positive legacies of all the colonialism that happened in the New World over the centuries,” the keyboardist said.

Another topic of discussion was the tradition of the singer-songwriter, thriving in Brazil at the time. Lebedinsky pointed out how artistically powerful such figures can be, from someone like Barbara Strozzi all the way to Bob Dylan and Taylor Swift.

Lebedinsky and soprano Danielle Sampson contributed strong performances of three works by da Câmara: Ouvi montes, arvoredos; Nunca fui falso ao meu bem; and Desde o dia em que eu nasci. That third song in particular is breathtaking in its melancholy, but the arrangements by Neukomm don’t quite capture that special, force-of-nature feeling that comes from experiencing the music of a singer-songwriter, or at least a single person accompanying their own voice.

The final takeaway from this episode is how impressively these distinct musics swirled together around a common theme. What also made it feel cohesive was the continuity Les Délices was able to maintain in the roster throughout the conversations and performances. That way, we could feel that we got to know these players as people and as musicians — at least a little bit — from the beginning of the episode to the end.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 9, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article