by Daniel Hathaway

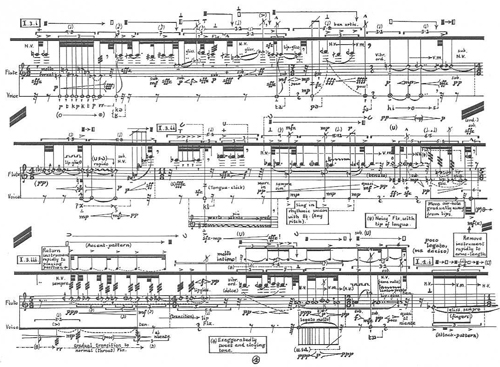

The audience heard Carlton Vickers, but they may not have seen him. Though the space was intimate, the special demands of works by Jason Eckardt, James Erber, and Brian Ferneyhough required Vickers to play from oversized scores deployed on multiple music stands that mostly obscured the flutist from view (see photo).

The four pieces on the program took Vickers and his flutes through every imaginable extended technique of which the instrument is capable. Eckardt’s Multiplicities (1993) alternates registers and involves spitting into the mouthpiece.

James Erber’s Desire Lines (2013-14) for alto flute — which the composer writes was variously inspired by a Roman road through the English Lake District, stories by Edwardian author Arthur Machen about the byways of suburban London, and the composer’s own architecturally-detailed street-dreams — is full of breathy meanderings and air sounds. (Another inspiration, Erber writes, was a mannerist painting depicting an explosion in a cathedral.)

Brian Ferneyhough’s Sisyphus Redux (2009) actually visits some conventional flute sounds. Playing on alto flute, Vickers also utilized microtones, rotated the mouthpiece of the instrument, and played more spit attacks.

Ferneyhough’s Unity Capsule (1975), the oldest work on the program, was also the most striking. Vickers said it took him ten years to prepare it, and that he was one of the few flutists in the world who was willing to take on the task. It began imperceptibly (Vickers crouched down behind a score page) then explored a vast range of sounds — tongue clicks, pops, murmured vocalizations — ending with a grand pause, then a sigh. The flutist looked exhausted after his 23-minute musical ordeal.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 22, 2016.

Click here for a printable copy of this article