by Jarrett Hoffman

That’s what I learned this past week, when I spent time on the phone with five of them to ask about their new chamber works being premiered by No Exit this weekend.

That new music ensemble, directed by Tim Beyer, will give free performances of these pieces at Heights Arts (Friday, February 15 at 7:00 pm), SPACES gallery (Saturday, February 16 at 8:00 pm), and WOLFS gallery (Friday, March 1 at 7:00 pm) in this second installment of the group’s Cleveland Composers Series.

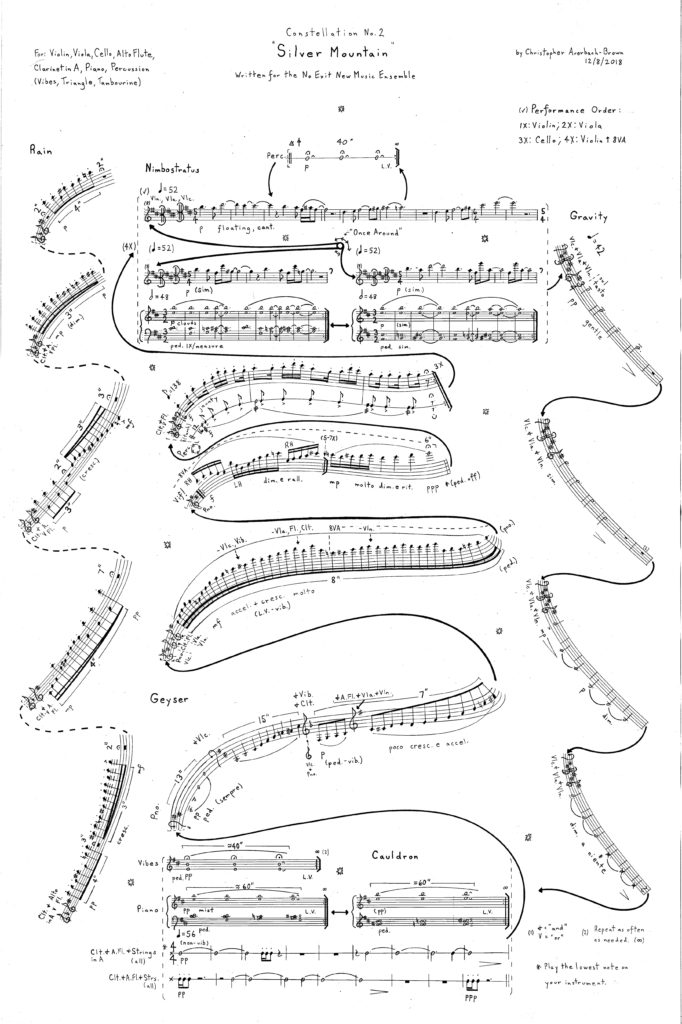

“It’s the basis of life,” Christopher Auerbach-Brown said of the water cycle, which inspired his new work Silver Mountain. Auerbach-Brown is the Director of Public Programs at the Conservancy for Cuyahoga Valley National Park. “There’s a section where things bubble and start getting exciting, and there’s a gesture that’s called the geyser where it kind of goes fwoosh!” The geyser “comes up through a mountain,” hence the title, and is followed by rain.

Before making a digital copy, Auerbach-Brown hand-wrote the score in ink on onion skin. “Part of that process involves measuring everything in advance — the sizes of measures, where they’re going to go on the page, and how their position reflects the piece from a visual standpoint,” he said.

Buck McDaniel, the 2018-19 Kulas Composer Fellow for Cleveland Public Theater, has been “sort of obsessed” with Missouri State University’s Max Hunter Folk Song Collection since he was a kid. “It’s great because it’ll have pretty accurate transcriptions, plus field recordings and the texts,” he said. “The nature of a lot of folk songs is that there will be ten versions of the same material, and here you can see the different traditions. It’s some very good ethnomusicology taking place.”

That Collection is where he discovered Loving Henry, a folk song about a woman who stabs and kills a man after he turns her down for another woman. (He seems to let her down pretty easy in this version, though in others, under titles like Young Hunting and Earl Richard, he tells her that a finer woman “than ten of you” is waiting for him. Bad choice.)

Working with a 1958 recording by Joan O’Bryant, McDaniel inserted an arrangement of the song into his new piece Light Down. The folk material “sort of sneaks up on you in some delicious ways,” he said.

He also had in mind what kinds of pieces No Exit likes to play — “I wanted it to be fun,” he said — as well as his experiences with Tim Beyer. “Every time you see him, he’s always telling you some terribly macabre story. He used to collect antique medical instruments, and I’m sure he still does. So I wanted to do something that would please Tim’s own sensibilities, and sort of be this abstract, dark meditation on Americana.”

The composer joked about naming the piece. “Loving Henry was originally going to be the title, but I didn’t want it sound like it was about a former lover of mine named Henry or something. My title actually comes from the first line of the song, where this female lover says, ‘Light down, light down, loving Henry,’ essentially asking him to stay with her in bed,” McDaniel said. “So it’s not about a power outage.”

She took photos of these textures, which gave her “more timbral information,” she said, in addition to informing the structure of the piece: at first mirroring photos that become progressively more rough in texture, then later more metallic. Khorassani noted, however, that she didn’t exclusively follow what she saw. “Sometimes I wanted to make changes musically.”

The composer said that her recent interest in combining visuals with her writing might be connected to her background in graphics, which she studied before composition. But she also just likes how photos and drawings give her something concrete to refer to. “They have a lot of information in a glance,” she said. “Instead of memorizing things, I have something saved that I can go back and review.”

Another fascinating concept surrounds Greg D’Alessio’s electroacoustic Many Doors. It’s made up of several short sections, mostly highlighting solo instruments, and the idea is that if any one of those sections were extracted to be played alone, it wouldn’t be the same, quite literally.

An example is The Secret Life of Birds, which was premiered by No Exit flutist Sean Gabriel back in 2016. That became one of this work’s episodes, but the version that will be heard as part of Many Doors has been abridged and altered.

“It’s like a mothership and these little pods that come out of it,” said D’Alessio, who teaches composition at Cleveland State. “Or like a network of related pieces that sort of feed into each other. That was the idea from the beginning, and for one reason or another it didn’t happen a few years ago, so I just did one of the solo pieces. But now I have a composite piece, and then conceivably will do another whole set of solo pieces so that you could recombine bits and pieces for whatever forces you have. It’s not like the usual concrete, freestanding piece that is just that thing and only that thing.”

D’Alessio imagines the project ideally in an electronic format. “Maybe there would be links, and you would be listening to the piece and say, ‘I want to hear more of the cello thing,’ and you could deviate into the cello space and then come back. But that’s down the road someplace, maybe.”

Many Doors honors the 10th anniversary of No Exit in a few ways, including its title, a play on the ensemble’s own name. “And I don’t know whether this stuff would stay if I made a concrete version of the piece, but for these performances I worked in some of the French production of Sartre’s No Exit from the ‘50s, and a little bit more of the playwright himself (pictured below).”

For some composers, a title comes at the very end of the writing process, almost out of desperation. But for Restless Voicings by Keith Fitch, he said, “I had that title for the last ten years, and I was waiting for the right piece. When Tim asked me to do something for No Exit’s 10th-anniversary season, I thought, this was the time to write that piece, whatever it was going to end up being.”

Fitch, who teaches at the Cleveland Institute of Music, actually keeps a list of possible titles in his studio. “I have my list that goes back to college, and now I look at them and think, oh my god, some of those are terrible!”

It’s just part of how he works. “I almost always have one or two options for a title as I’m beginning a piece,” he said. “Because for me, it’s one of the first windows into the piece. We go to a concert and we see a title, and whether it’s poetic or evocative or compelling, that’s our first entrée into the piece — assuming it’s not something abstract, like String Quartet No. 4. So it’s hard for me personally to write a piece without having an idea of what that first encounter with it will be. But I have students and lots of composer friends who just struggle and struggle and struggle with titles. They write the piece and then they never know what they’re going to call it. I’m just very different that way.”

This title popped into Fitch’s head over a decade ago — not when he was up late at night philosophizing about the universe, as we might imagine composers do, but simply when he misheard something during a car ride.

“I was teaching at Bard, and Joan Tower and her husband Jeff were driving me to the train station to go back to New York. Jeff was taking jazz piano lessons at the time. He was talking about his lesson that day, and he said, ‘Rootless voicings,’ which is basically when you’re harmonizing the melody, but there’s no root of the chord — like Bill Evans’ voicings. But I misheard it as ‘Ruthless Voicings’ and I thought, ‘That’s a great title for a piece. Now I just have to figure out what the piece is going to be.’”

Scores and materials courtesy of the composers.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 12, 2019.

Click here for a printable copy of this article