by Daniel Hathaway

On Wednesday, the harpsichord master classes split into two concurrent sessions, one led by Lisa Crawford, the other (mine) by Mark Edwards. After hearing the C-minor Prelude from The Well-Tempered Clavier Book One (advice: use wrist rotation to mirror the texture of the music; differentiate between speaking and singing) and Antoine Forqueray’s La Montigni (originally a viol piece, so prioritize how to play the notes in the bass line; to avoid “claw hand,” let the hands free fall onto the keyboard from overhead height), I was up next with a rather bizarre piece by an English virginalist.

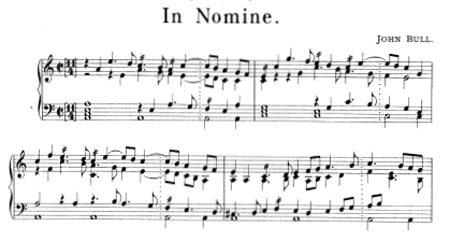

One of John Bull’s In Nomines from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book is in 11/4 time, a meter described in a lecture to London’s Musical Association in 1895 as “two bars of common time and one of ¾ time, the effect not being so annoying to the rhythmic sense as might be imagined.”

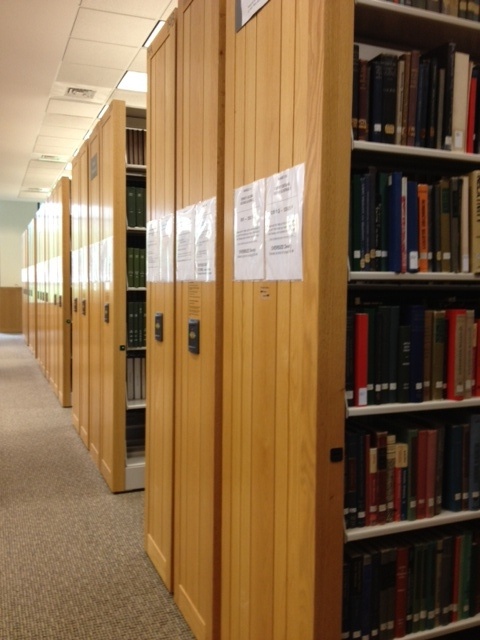

Because there are a number of places in the piece where accidentals are questionable or ambiguous, Edwards emphasized the importance of using a good edition. Was this piece included in Musica Brittanica as well as in the less-reliable but readily available Fitzwilliam edition? I confessed that I went looking for “MB” but that collection lives on the second floor of the Conservatory Library in the moveable stack area — you have to go through several arcane moves to unlock and crank successive rows of books to gain access to what you want. (I’m not the only one who, frustrated, gave up his quest.)

My colleague Brendan Barker happened to mention that the harpsichord master classes seemed to be designed for performers who were contemplating a solo career on the instrument — which he was not. I sat down with him to ask about his own reasons for attending BPI.

“I did graduate work at Notre Dame with a bunch of great professors, but especially Alex Blachley and Mary Anne Ballard — she’s integrally involved here with the viola da gamba, but she’s also a big advocate for the program. I found out from my friends who have come to BPI in past years how awesome it was, and I wanted to spend some time intensively studying continuo. I could never see myself as a harpsichord soloist, but I’d play continuo in a heartbeat. I’ve always been interested in the image of the conductor as keyboardist leading an ensemble from within.

Barker had met Joe Gascho during a short master class at Notre Dame, and was eager to pursue continuo playing with him at BPI. “He’s fantastic to work with. He makes such a painful subject approachable and entertaining. I put his continuo classes down as my favorite on the student survey.”

During the first week, Barker was in an ensemble that included two harpsichordists. “That was very helpful to me because it was my first experience ever playing continuo. With two players, you can create more texture, and it’s less stressful when you have more people to share the responsibility. My partner was more skilled — she just finished a degree in harpsichord at Eastman — so she was the leader, and I was just figuring out the chords and adding things as I was able. I jokingly referred to myself as the ‘ripieno’ harpsichordist who joined in the tuttis in order to produce a larger, more varied texture.”

The 2:00 pm student concerts on Wednesday and Thursday continued the first week’s parade of Telemann fantasias for solo instruments. It’s been ear-opening to hear so many of his one-liners in a short space of time. One of the most prolific composers of all time, Telemann is endlessly inventive in these pieces — which street musicians and subway buskers might well adopt to improve their game.

Before our 3:00 pm ensemble coaching, I got together with my harpsichord henchperson, Michael Mishler, to plot our moves in the Mouret suite. I suggested following Brendon Barker’s lead and functioning as the ‘ripieno’ player, adding emphasis to passages where the trumpet played. During the coaching session, John Thiessen patiently and painstakingly worked us through details of ensemble, rhythm, and dynamics, and Joe Gascho dropped in to suggest fancying up the ‘ripieno’ harpsichord part. “What’s the only chord in the first movement that isn’t either a D or A chord?” “A G chord.” “Well, make something big out of that.” And “Why play such a skinny chord here?” “The bass note is D above the staff, so there’s not much headroom.” “So play it down two octaves and make a big deal out of rolling the chord.” “I’m allowed to do that?”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com July 3, 2017.

Click here for a printable copy of this article