by Timothy Robson

Such was the case this weekend with the presentation by Opera per Tutti of French composer / conductor Frédéric Chaslin’s Clarimonde, in collaboration with Cleveland Public Theatre (CPT) and New York’s On Site Opera.

Performed in CPT’s intimate James Levin “black box” Theatre, the production marked the beginning of a new series, “Opera Nuova” (New Opera), which will feature a new or recent opera each fall. This performance of Clarimonde was a “concert reading” — the singers used scores but were in costume with simple movement by stage director Scott Skiba. The piano reduction was ably played by Lorenzo Salvagni, and Katherine Kilburn conducted from a stool at the front of the playing area.

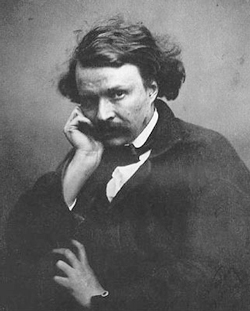

The libretto by P.H. Fisher is based on Théophile Gautier’s novella La Morte Amoureuse (1836, author pictured above), an intriguing story full of operatic promise. It concerns a young priest, Romualdo, who is tempted by the glamorous vampire Clarimonde to join her and her mentor, the Vampire Maker, for eternity. Romualdo is ultimately saved through the devotion of his bishop.

Frédéric Chaslin has impeccable musical credentials as pianist, conductor, and composer, having served as musical assistant to such luminaries as Barenboim and Boulez. His previous music theater works included one based on Wuthering Heights. But Clarimonde suffers from two basic and interrelated deficiencies that plague many contemporary operas: too many words and too many notes. The musical style is tonal, but the music is constantly busy. There are passages in other operas, even those with otherwise very large orchestras such as Berg’s Wozzeck or Britten’s Billy Budd, in which the composer accompanies the singers by just one or two instruments. In Clarimonde, there is seldom a moment of repose in which the texture is thinned out. As a consequence, the singers were often forced to oversing, and the generally loud dynamic proved tiring to listen to over the 90-minute duration of the opera.

Also, there were few melodic guideposts to inform the listener’s notion of the characters. The music was an unending twilight zone between nondescript arioso and surging climax. Tellingly, I did not read the two-page plot synopsis before the performance; afterward, when I did, I repeatedly thought, “Oh, that’s what was going on.” There are few real “arias.” Only Clarimonde (vividly sung by soprano Rebecca Freshwater) has an extended scene in which she remembers her childhood and contemplates her vampiric state, with its contradictory blessing and curse of ageless youth and beauty.

It seemed that the composer was differentiating the music for different characters. The Clarimonde/Vampire Maker music felt much more like Broadway song, while the music of Romualdo and his Bishop (baritone Benjamin Czarnota) sounded more stereotypically “classical” in style. If this was indeed true, it was a good idea and should be developed even more.

The Vampire Maker (Brian Keith Johnson) resembles the character Sportin’ Life in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. But other than his many clarion pronouncements (“Long live Clarimonde”), there was little development of his character.

Romualdo (tenor Benjamin Bunsold), passionate in his delivery and convincing in his attraction to Clarimonde, is more fully drawn. The young priest’s conflict between church and eternal love is evident. The Bishop makes appropriately church-like, if not poetic, statements to the priest. Yet the ending of the opera did not seem tragic enough. Clarimonde is consigned to a fiery death; do we care what happened to Romualdo after this episode?

Despite these criticisms, there are lovely moments in the score, sometimes resembling Debussy or early Messiaen. The softer music was among the most effective. Clarimonde is still a work in progress, and this was not a full staging. With further slicing, dicing, and rewriting, its full potential could be realized.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 3, 2014.

Click here for a printable copy of this article