by Kevin McLaughlin

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Pianist Yuja Wang is a dazzler. She has a way of dressing, of taking the stage, and of bowing that bespeaks confidence and star quality. Add to those a suspenseful entrance (a few minutes overdue), apparent nonchalance at a last-minute conductor change — assistant conductor Daniel Reith in for music director Franz Welser-Möst — and an astonishing keyboard technique, and you get excitement.

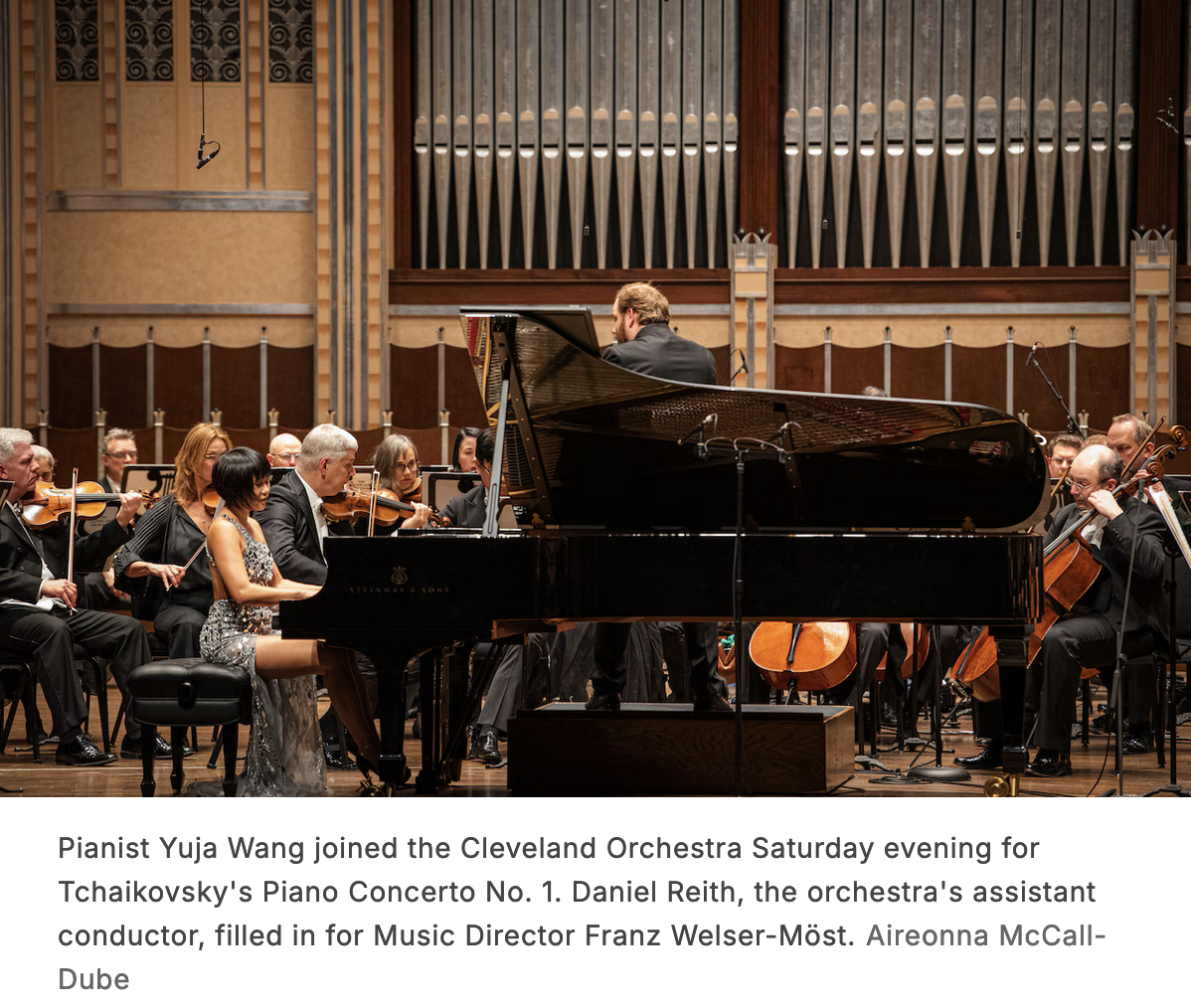

The audience was buzzing with anticipation on Saturday evening March 22 at Severance Music Center for Wang’s appearance with the Cleveland Orchestra in Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1.

To be fair, the delayed entrance likely had more to do with a needed meeting between pianist and conductor before performing the work together. Reith, who received word of the change only two hours before the concert, deserves much of the glory for what followed.

With Wang, virtuosity is not mere show, it’s an essential part of her being. Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto may benefit from a player’s passion, but for Wang there may not be any other way to behave.

She played with disarming power and clarity, handling Tchaikovsky’s terrifying double-octave passages in the first movement with stunning ease, and the many solo moments as if they were no challenge at all. And she lavished tenderness on Tchaikovsky’s lyrical melodies.

She cultivated genuine rapport with the orchestra’s wind soloists, including a seamless handoff to flutist Joshua Smith in the middle Andantino movement. She showed both a command of the spotlight and the ability to relinquish it, as in the dancelike Prestissimo section of the same movement. Or in the folksy finale, where Reith pushed the orchestra close to Wang’s brilliance. Sadly, even after four curtain calls, no encore was forthcoming.

Having performed Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony in New York’s Carnegie Hall a week ago, the orchestra was primed and ready for this one. Reith coaxed superb playing from every section, but the brilliance of the brass, often in announcements of the Fate theme, is what left the greatest impression.

The symphony begins in the dark. Low clarinets introduce Fate and set a discouraging course before matters grow in urgency and drama. Reith’s tempos were brisk, but he was still able to maintain masterful control and stake out a wide dynamic range. A heart-wrenching plea in the low strings gave way to the slow movement and a horn solo, played magnificently by Nathan Silberschlag.

The waltz in the third movement was lilting and elegant, as bubbly as champagne, finally cresting to heart-on-sleeve passion. The Fate theme reappears at the beginning of the finale, but is transformed, as if weary from a long journey. Reith marshaled his forces one last time, and an obligato trumpet solo by Michael Sachs at the coda concluded the work triumphantly.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 26, 2025.

Click here for a printable copy of this article