by Daniel Hathaway

If the Oberlin Conservatory of Music kept a trophy case in its entrance lobby, it would need a new shelf to show off the awards that Oberlin organ students Katelyn Emerson, Parker Ramsay and Dexter (“Tripp”) Kennedy have recently won at competitions in France, Russia and the Netherlands.

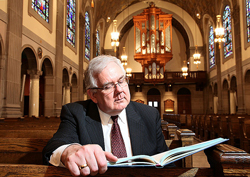

Though not so familiar to the general public as the big piano competitions, the Mikael Tarierdiev, the Pierre de Manchicourt, the Sweelinck and the Chartres contests command an imposing reputation in the world of international organ playing. The recent awards underline Oberlin’s continued prominence in the training of young organists. All three of the winners are students of James David Christie.

Katelyn Emerson

Third place and special Krasnoyarsk Philharmonic Society prize, VIII Mikael Tarierdiev International Organ Competition, Kalingrad, Russia, September 9, 2013.

Second prize (Jean Boyer award), Fifth International Organ Competition Pierre de Manchicourt, Béthune & Saint-Omer, France, September 30-October 5, 2014.

Katelyn Emerson, a native of southern Maine, is in her final year at Oberlin, where she is pursuing a double degree in organ performance and French, with minors in music history and historical performance with an emphasis on the fortepiano. Emerson discovered the organ when she was singing in a children’s choir in Portsmouth, NH. Her choir director was on the board of a young organists’ collaborative and suggested that she pursue organ lessons. “I began concentrating on the organ during my junior year of high school,” she said in a recent interview in the conservatory’s Skybar. “Everything just came together.”

Her interest in the organ connected neatly with her fascination with French when she came to Oberlin. During Christie’s sabbatical, she had the opportunity to study with visiting professors Olivier Latry (organist of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris) and Marie-Louise Langlais (wife of the late French organist and composer Jean Langlais). “My Francophilia just loved it!” she said.

James David Christie says of her, “Katelyn has a wonderful musical talent. She works hard, and she’s a repertory hound. She’s learned a staggering amount of music at Oberlin.”

Emerson has brought back two international prizes. In 2013, she was admitted into the VIII Mikael Tariediev International Organ Competition in Kalingrad, Russia, through a live audition at the University of Kansas. Four Americans were selected to compete along with 21 Russians in Kalingrad, a strange little niche of the world. “It’s surrounded by Poland and Lithuania, but there are a ton or German influences,” Emerson noted. She won third place and the special prize of a concert at the Krasnoyarsk Philharmonic Society.

The 2014 Pierre de Manchicourt competition in France required a recording as the first round. “Then,” Emerson said, “there were performances on two different instruments in each of the following rounds, which lasted for eight days in Béthune and St. Omer, cities two hours apart by train.”

Unlike piano competitions, where all instruments have 88 keys and the same three pedals, organs can be wildly different in style and accoutrements. “The second round in the Russian competition was at the Philharmonic, where the organ had a strange pre-set system for the stops,” Emerson said. “In France there were no pre-sets at all. One organ there was a recent instrument in the 17th century North German style and the other was an early Cavaillé-Coll.”

Emerson found the competitions exhausting. “You prepare as much as you can, but there were seven finalists in the last round of the Russian competition, which left less than two hours of practice time on the instrument. You learn to set stops quickly and hope they stay! I had wonderful American assistants.”

Emerson also had the valuable support of her mother as a travel companion. “She was the mom to the Americans. And she’s also an occupational therapist with a specialty in upper extremities. When I had a slight flare-up of tendonitis, she was there to tape me up.”

After she graduates from Oberlin, Emerson says she looks forward to earning an advanced degree “in only one subject!” When we talked, she was in the throes of completing her graduate school applications to Yale, McGill and Rice, as well as applying for a Fulbright to France.

Parker Ramsay

First Prize, Sweelinck International Organ Competition, Amsterdam and Haarlem, The Netherlands, September 24-26.

Parker Ramsay, a native of Nashville, TN, is in his first year of the master’s program in Historical Performance in organ and harpsichord, having graduated from Cambridge University in 2013 with a B.A. in History. While at Cambridge, he had the distinction of being the first American appointed as organ scholar at King’s College, where he was heard around the world last year during the famous Christmas Eve Festival of Lessons and Carols. “I faked an accent,” Ramsey joked in a telephone conversation, when asked how a non-Brit got tapped for that position.

Oberlin represents Ramsay’s first foray into full-time musical studies, though the King’s position exposed him to a wealth of repertoire and especially awakened his interest in ‘early’ music. “With all the exposure to sixteenth and seventeenth-century music, I really got the bug. At King’s there were 25 hours a week of rehearsals and services with all kinds of repertory, from Dufay to new works that were only two months old.”

The Sweelinck Competition suggested itself when Ramsay was working on Dutch music for a lecture recital. “Ah, that sounds like the competition for me,” Ramsay remembers thinking. “It fit the bill for what my passions were and I was enthusiastic in preparing for it. There was a prescribed list of music for the pre-selection, but not for the rounds. You were required to play one Sweelinck work and two Bach works, then creatively form programs related to Bach and Sweelinck that were appropriate for the instruments and their tuning systems.”

Those instruments were the 1964-1965 Jürgen Ahrend choir organ at the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam, where Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck himself once performed as city organist, and the 1738 Christian Müller instrument at the Grote Kerk or St. Bavo Church in Haarlem. The Ahrend had been put into mean-tone temperament in 2002 by Flentrop Orgelbouw, while the Müller is in equal temperament. “There are a lot of arguments against playing the Micheangelo Rossi chromatic toccata in mean-tone,” Ramsay said, though he did it anyway. “The Müller is wonderful. I’d played it several times before. It’s been modernized slightly but it plays old music well. Everything sounds like music on that instrument.”

Ramsay found the lack of practice time during the competition daunting, but attributes his level of preparation to the unparalleled number of organs in Oberlin’s collection. “I got to over-prepare. Oberlin is very special. I told other students that it’s easily possible to practice for four hours a day here. They said they could only manage about two in Europe.”

At the end of the competition, Parker Ramsay managed to pull off a coup, winning first prize on September 26 in a competition that hadn’t awarded the top honor for several years. In the old days, a first prize in the Sweelinck guaranteed an organist a series of recitals organized by the competition in addition to 3,000 Euros in cash, but that wasn’t the case in 2014. “The organizers said they’d become so accustomed not to hand out a first prize that they decided not to arrange for recitals this time,” Ramsay said.

In addition to his keyboard skills, Parker Ramsay is an accomplished harpist of the French school of playing. He’s also recently collaborated with a fellow HP student to form an ensemble called The Tenth Muse, which uses historical instruments to perform both early and contemporary music, pointing up the connections between the two. “Next semester, I’ll do a program combining organ and electronics and we’ll invite spoken word artists as well. The idea is to take historical performance practice and contemporary music out of their own spheres.”

James David Christie is impressed with Ramsay’s eclectic talents. “He’s a complex musician and a Renaissance person. He can play early music like a god, but he does all periods, and his Liszt Ad nos was one of the best student performances I’ve heard. At the Sweelinck, I felt like I’d never heard those pieces before. If the curtains were up, you wouldn’t know it was him, and that’s the way it should be.”

After earning his master’s at Oberlin, Ramsay plans to apply for a Fulbright to France. Asked about his eventual career plans, he said, “I haven’t the faintest idea! I still have a few years in grad school, then I’ll hopefully have a bank account that’s in the positive.”

Tripp Kennedy

Grand Prix de Chartres, 24th International Organ Competition, Paris, France, October 28-November 8, 2014.

Tripp Kennedy, a native of Grosse Point, Michigan, is currently pursuing his artists diploma. He got bitten by the organ bug while in high school. “I was always interested in the variety and power of the instrument,” he said in a recent phone conversation. “My high school choir director was convinced that I was going to be the next Leonard Bernstein because I could hear the kind of orchestration you can achieve in organ playing. She let me miss choir one day a week to take a lesson at Christ Church, Grosse Point — the same church where I’m now assistant organist.”

Kennedy had already experienced Oberlin through its summer high school academy for organists, and it was his initial stop when he was shopping for undergraduate school. “I knew from the first moment that it was a good match. The organ collection is second to none, and Jim Christie has a real interest in and involvement with his students. He can clap you on the back and say, ‘Hey, whatcha doin’?’ I didn’t want an intimidating teacher. I wanted one you could crack a joke with if things weren’t going well.”

Christie remembers Kennedy in his undergraduate years as “full of life. He’s a major talent who prepares well and has an interesting musical personality. I love his playing. Going to Yale after Oberlin was the perfect thing. I told him, now you’re an adult, and you’re going to do this for yourself.”

Kennedy studied for his master’s with Martin Jean (himself a Grand Prix de Chartres winner). At Yale, he found fewer distinguished instruments but a greater challenge. “You had to work to make those organs sound good. That and the emphasis on church music made me more well-rounded, otherwise I wouldn’t have the job I have now playing Evensongs and Anglican chants, which I love doing.”

Kennedy finds great irony in his experience with organ competitions. “It’s funny. My senior year at Oberlin I sent in three applications and didn’t get accepted to any of them. Then this fall I got into Chartres and won!”

Another irony: “I never set foot in Chartres,” Kennedy said. While the first two rounds of the Grand Prix de Chartres are routinely held in Paris because of the greater number of practice organs in the capital, the final round this year was held at the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris because of a nave renovation project at Chartres Cathedral. “It was the first time since 1971 that the competition didn’t end there.”

While Emerson and Ramsay had the possibility of more repertoire options and choices in their competitions, Kennedy had to play the same music in all three rounds. “The exact same pieces in the exact same order,” he said. And while constructing a cogent program figures prominently in other contests, “here, you weren’t judged on making an artistic statement through your repertoire choice.”

An odd veil of anonymity surrounded the proceedings. “There were twenty-two candidates in the first round. You picked numbers and didn’t know anyone’s identity,” Kennedy said. “What surprised me was that in the second round you received a new number, so there was no way to judge a candidate cumulatively.”

Kennedy’s eventual victory came with a 5,000 Euro prize and what he calls “a full dance card” for the future, with thirty concerts designated for the first-prize winner, and ten to twenty for the others. Also ironic is that one of the “fringe” events for competition runners-up is a concert in Chartres Cathedral. Though Kennedy won’t be playing there, he can look forward to playing recitals in the Berliner Dom, the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Hall, England’s St. Alban’s Cathedral, and venues in Spain, Italy, Luxembourg, Iceland and Slovakia.

Based in Grosse Pointe, Tripp Kennedy travels to Oberlin once every other week to work on his artist diploma and to teach organ at the College of Wooster, where he’s recently been appointed to the music faculty and is busy rebuilding their organ program.

A follow-up with James David Christie

Before they even reach that point, Christie has salient advice for students who want to pursue the competition circuit. “I tell them to make sure they choose a competition that’s right for them, one where they’re comfortable with the repertoire, and comfortable with the judges. There are a lot of factors to consider.”

Christie, who has served on over fifty competition juries, maintains an open mind about matters of interpretation. “Nothing gives me more happiness than when someone plays something completely different from they way you’d do it, but they end up convincing you.”

How does Christie clear his head after so many hours of listening? “I’m used to it. The hard thing is hearing the same pieces over and over. You have to take a breath and imagine it’s the first time. You can’t let your mind wander or be thinking of anything else.”

And what do competitions do for the careers of musicians? “Some do a lot of good, some are worthless and do nothing to advance the development of a career. Those that offer tours, years of management and recordings are the real McCoy.”

A seasoned competitor himself, Christie ends our conversation with his own, now humorous story about playing in the Bruges International Competition in 1976.

“I was going to win, and I prepared like you wouldn’t imagine. I had the whole repertoire memorized four months in advance. One day in Bruges I was playing through the Bach G-Major Prelude and Fugue, BWV 551. The girl who was practicing after me said, ‘How do you have time to practice a piece that’s not required?’”

Christie discovered to his horror that he should have prepared the other Bach G-Major, BWV 550, a piece he had never even heard before. His perfectly-laid plan for winning the contest suddenly fell apart.

“I sweet-talked my way into a cloister of nuns and stayed up all night learning the piece on an 8’ flute stop. The sisters came in to sing a service at 4 am and brought me coffee and cookies.”

Having nearly memorized BWV 550, Christie managed to calm himself down the next day when his turn came to play — at least until the pedal cadenza, “when my ear failed me for the first time in my life. I finally dived for a note and got to the end. One of the jury told me afterwards that if I’d played that right I would have moved on. Anyway, I stayed to the end of the competition and played cheerleader and court jester for the rest of the team!”

As a happy sequel to that story, Christie returned to the Bruges International Organ Competition in 1979 and became the first American ever to win its first prize.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 23, 2014.

Click here for a printable copy of this article