by Jarrett Hoffman

One of the Sphinx Organization’s most important representatives onstage is the Sphinx Virtuosi. That string orchestra, primarily made up of Sphinx Competition alumni, is dedicated to increasing racial and ethnic diversity in classical music.

The Virtuosi embody that mission not only in their roster, but also through their programming. On Wednesday, May 26 at 7:30 pm, in a concert presented by Tuesday Musical, a quintet from the ensemble will visit E.J. Thomas Hall to share “Land of the Free.” The program includes works by Xavier Foley, Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, Andrea Casarrubios, Samuel Barber, and Antonín Dvořák. (Tickets are available here.)

In addition to showcasing a diversity of American and American-inspired composers, the selections explore interesting territory when it comes to instrumentation: chamber orchestra pieces scaled down as quintets, string quartets scaled up a notch with a double bass, and a solo cello piece in the middle.

The string-orchestra category consists of Foley’s Ev’ry Voice and Perkinson’s Sinfonietta No. 1. In fact, the Foley piece has a history with even larger forces: he was commissioned to create one version for the full Virtuosi, and a second that would also incorporate Sphinx’s vocal ensemble Exigence.

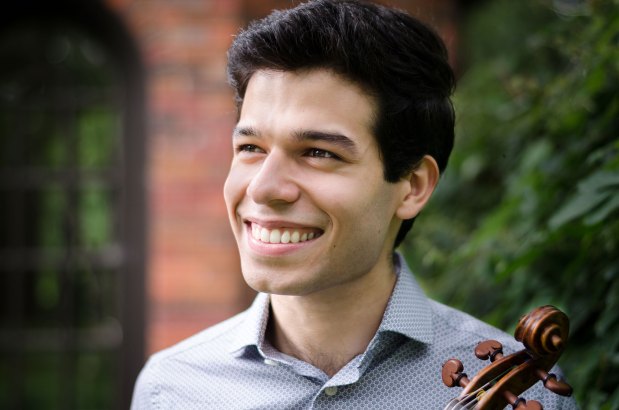

With that in mind, when I reached Virtuosi violinist Rubén Rengel for an interview, I was curious to ask about the experience of playing large-scale works in a quintet setting — do the players adjust their level of sound or energy, or do they just let the music exist in a different way?

That concept of straddling two different worlds of sound will also apply to the Adagio from Barber’s Op. 11 Quartet for Strings and the Finale from Dvořák’s Op. 96 “American” Quartet.

Rengel actually prefers the experience of the Dvořák with the addition of double bass. “It’s much more exciting, and the bass provides a lot of power.” Meanwhile, the Barber already has a history of expanded forces, having been arranged later on by the composer for string orchestra — the famed Adagio for Strings. “Most people know it in that form, so it’s again a combination where we live in both versions.”

Beyond the topic of adaptation and its effect on performance, it’s worth discussing the real-world relevance of the two newest pieces on the program, both written in 2020.

Casarrubios’ SEVEN for solo cello is a tribute to essential workers during the time of COVID-19, as well as to anyone who lost their life or is still suffering from the pandemic.

The events of last year are also in the DNA of Foley’s Ev’ry Voice, an homage to Lift Every Voice and Sing, often considered the Black National Anthem. As described in the program notes, the piece perhaps encourages the audience “to look and listen anew, beyond the isolation of the global pandemic and the racial and cultural divide in our country.”

When those topics are part of the story behind a composition, does Rengel have them in mind while performing, or does he simply focus on the music and let the audience take away any broader ideas?

“The message that we bring with Sphinx is always on our minds as we perform,” he said. “Our programs have powerful messages, and I think Xavier’s piece embodies that in a powerful way. He does an amazing job of incorporating the history behind the anthem, but also combining it with influences from many other genres.”

Each member of the Sphinx Virtuosi quintet visiting next week — Rengel, violinist Jannina Norpoth, violist Dana Kelley, cellist Thomas Mesa, and bassist Christopher Johnson — has a fascinating story as a musician. One reason I was keen to interview Rengel is his connection to Northeast Ohio, having studied as an undergraduate with Jaime Laredo at the Cleveland Institute of Music from 2012 to 2016.

“I loved my time in Cleveland,” Rengel said. “It was the first city that I moved to from Venezuela, and it was a great time with great musical development for me. I’ve been back since I graduated maybe three or four times, and it’s so special every time. I still have really good friends there.”

We also discussed his interests in other genres. “My dad is a Venezuelan folk musician, so I basically grew up improvising,” he said. “He would grab a guitar, and I would sit at the piano and accompany him.” Rengel’s sister is also a violinist. “At home we would have lots of music and collaboration, which was super fun.”

After being raised in the tradition of folk music from his home country, Rengel became interested in other kinds of music — “Latin American genres, and some jazz as well,” he said. “Even though I mostly play classical music now, I always try to bring some of that into my programming.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 18, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article