by Daniel Hathaway

Originally titled Hymne au Saint-Sacrement, Messiaen had to reconstruct his early vision of the Eucharist from memory in 1947 after the 1932 score and parts were lost during the Second World War. Launched with an upward swooping gesture, the piece settles in for a meditative passage in the violins surrounded by shimmering colors before ending amid ecstatic trumpet fanfares and swooning horns.

Georges Prêtre and The Cleveland Orchestra introduced Chronochromie (1959-60) to the United States in 1967. Written to explore the interaction of time and color, the work is organized like an ancient Greek ode with two Strophes and Antistrophes, followed by an Epode, and bracketed by an Introduction and a Coda. A complicated mathematical structure is buried deep in its DNA, but perched on its surface is a collection of Swedish, French, Mexican and Japanese birds, all tweeting their distinct, carefully researched songs, sometimes in a rapturous din of sound. (In the Epode, eighteen string players each play a different avian tune).

The Orchestra gave the work a brilliant reading, with special contributions by percussionists Marc Damoulakis and Tom Freer, who played breathtaking mallet duets with verve and precision. Chronochromie ended in what can only be described as glorious noise, the kind that only Messiaen can conjure.

It took until 1970 for The Cleveland Orchestra to play its first performance of Dvořák’s fifth symphony (under Michael Charry). Though not one of the composer’s most famous works, the 1875 piece is full of charm and character, evoking both the pleasures of a ramble through the forest and, in its Scherzo, the exuberance of Slavonic folk dance.

Welser-Möst led a dynamic performance, relaxed enough to let the fast movements breathe but fired-up when the music demanded it. Principal wind players contributed handsome solos, including oboist Frank Rosenwein, flutist Joshua Smith, hornist Richard King and (assistant principal) clarinetist Daniel McKelway, who also took a turn on bass clarinet in the finale. Unleashing just enough horsepower to surround the rest of the Orchestra with a golden glow, the brass propelled the symphony to a magnificent conclusion.

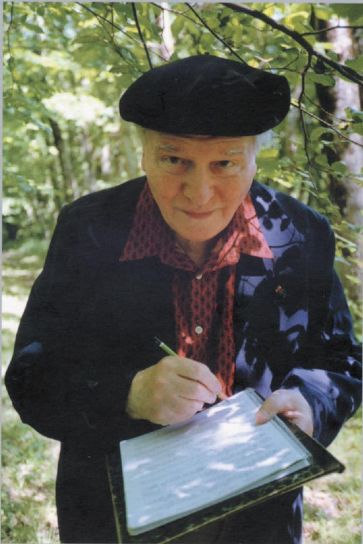

Photo: Messiaen in the woods collecting birdsong.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 2, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article