by Daniel Hathaway

Ying Li, 23, from Beijing China, moved to the U.S. when she was 14 to study at the Curtis Institute with Jonathan Biss and Seymour Lipkin, where she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 2019. She is now enrolled in the master’s program at Juilliard, studying with Robert McDonald.

Li chose a wide-ranging program of music by Mozart, Richard Strauss (filtered through Percy Grainger), and Bartók that showed different facets of her musical personality.

Her graceful, lyrical reading of Mozart’s Sonata No. 13 hurried agreeably through little flourishes in the first movement, and pointed up structural events like excursions into the minor mode. She acknowledged the extra expressiveness of the chromaticism in the slow movement, and made the most of the concerto-like final rondo with its embedded cadenza.

It was sometimes difficult to match up what we saw (rendered from a number of angles on the big screen above the stage) with what we heard in the music. The pianist indulged in the de rigeur practice of projecting outsized facial expressions, sometimes looking tormented during perfectly sunny passages. And while she emphasized special little moments in the score, she let others pass without much musical comment.

Li abandoned facial histrionics altogether in the Bartók Sonata, getting right down to business and producing a muscular, tightly rhythmic performance that was at the same time open-textured and laid-back. Her playing in the final movement was just as wild as the music dictated, but well-controlled.

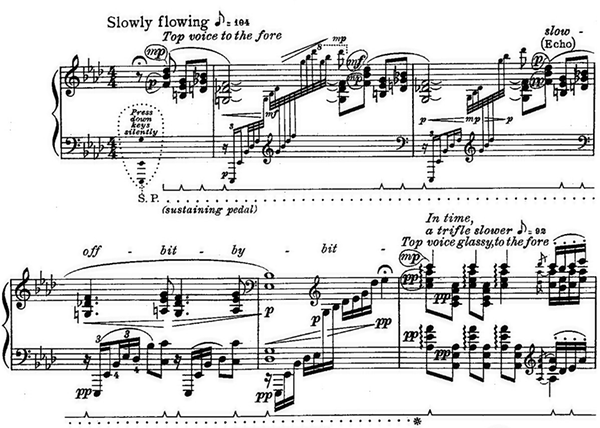

The Australian-born pianist and arranger was a devoté of Strauss in general and Der Rosenkavalier in particular, as well as an advocate for the exploration of all the effects possible on the modern concert grand piano — including that mysterious third pedal that kicks up the dampers, allowing certain notes to continue sounding while other music goes on.

Li was in total command of Grainger’s elaborate score and its fussy notations, using the Steinway as a versatile machine to mimic orchestral colors and produce other-worldly effects.

She ended her set with one of the competition’s required show pieces, Lalo Schifrin’s Themes from Mission Impossible, arranged for virtuoso piano by Alexey Kurbatov. This led directly — after a ten-minute pause — into a performance of the same piece by Honggi Kim at the top of his set, and the opportunity to compare the personalities of two different interpreters on the same musical turf.

Kim seemed more at home in the ethos of the TV series that ran from 1966 through 1973 and was briefly revived from 1988-1990. His take on the music clearly revealed the jazz origins of the Argentine-born composer who played with Piazzolla and created so many memorable title songs for film and television. Li’s playing was more objective, yet thrilling on its own terms.

Although written during the span of three years between 1832 and 1835 and published together in 1837, there’s nothing to suggest that the composer intended the twelve pieces to be performed together on the same program. Kim took several chances by programming them all at once, not the least of them inviting fatigue on the part of both performer and listener.

On the other hand, these twelve pieces are so varied that they’re continually interesting, yet so spiritually connected that the pianist was able to provide a convincing through-narrative. His pacing and spacing of the individual Etudes was masterful, and he connected the last three in a brilliant display of technique and musicality.

Throughout, Kim’s keyboard manner was calm and efficient. Even No. 11, the famous “Winter Wind” that seems to blow nobody good, fell neatly into place under his confident fingers.

Photo credits: Gregory Wilson.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com July 30, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article