by Jarrett Hoffman

Through commissions from CityMusic, that author’s texts have been set to music by Jasmine Barnes and Jessica Meyer in works for string quartet and soprano that will be heard for the first time — the latest of several new pieces by women composers that have been premiered during the organization’s 2021-22 season.

The program, titled “Slavic Village Then and Now,” also includes music by a pair of Czech composers: Antonín Dvořák and, by ancestry, Cleveland-born Charles Rychlik, who lived on Fleet Avenue in Slavic Village, and who crossed paths with Dvořák during studies at the Prague Conservatory.

Performances will take place on Friday, April 8 at Lakewood Congregational Church and Sunday, April 10 at Shrine Church of St. Stanislaus, both at 7:00 pm. Admission is free — RSVP’s encouraged — and a livestream option has been added for Friday’s concert.

As is often the case with projects in the music world, this program wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for a random and unlikely connection. Weatherspoon, who goes by their surname, was a classmate of Hashizume’s daughter at the Hawken School, where a writing presentation made the CityMusic concertmaster and Cleveland Orchestra violinist aware of the poet.

“The way Weatherspoon spoke was so striking that I was just immediately drawn to it,” Hashizume said during a recent telephone conversation. “But at the time, I didn’t know anything about them or their poetry.”

Introduced to the art form at age 12 by a middle school English teacher, Weatherspoon later received a scholarship to attend Hawken, during which time they became outspoken about anti-racism in speech-and-debate competitions nationwide. One topic they addressed in their oratory is Ebonics — its linguistic legitimacy, its place in the culture and history of Black Americans, and the harm that is caused when people look down upon it.

Now an English major with a concentration in creative writing at Bowdoin College, Weatherspoon has self-published two collections of poetry: To, Too Many Children and I AM KING. A third book, The Anniversary of When I Ran Away, will arrive later this month.

In separate phone calls, the two composers began by describing their reactions to Weatherspoon’s work.

“This is the kind of poetry I’m always looking for,” Jessica Meyer said. “Very intense and visceral, with a clear narrative.”

She recalled her own burst of creativity during high school, around the same time Weatherspoon wrote the poems that she chose for her piece. “I was writing my music as a way to figure out my adolescent self and how I functioned in the world,” she said. “So I was taken by seeing another adolescent trying to figure out the world and putting that in an artistic format. I felt a kinship there.”

She also found it significant for someone so young to be able to see their writing set to music. In one of their early conversations, they discussed how young people’s ideas are not often invited or valued by adults. “And I thought, how befitting that these words written by a young person are profound — they’re beautiful,” Barnes said.

She drew the title of her piece, Might Call You Art, from a Weatherspoon poem that spoke to her own experiences in a way that felt rare from a work of text. “Especially as a Black artist, it often feels like I’m not valued as a human being if I’m not creating art.” A related concept: feeling like she would be perceived as a threat if she didn’t create art — if she weren’t associated with the classical community. “I’m not saying I feel these things all the time, but I’ve definitely felt them before.”

She included quotations from The Star-Spangled Banner and the spiritual Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child in her piece as part of an aim to musically express “the sorrow that exists in Blackness in America,” she said. “Not to say there isn’t joy or our own personal complexities, but sorrow is definitely a shared experience amongst the Black community in a particularly directed and focused way.”

Art song, opera, Broadway, and pop make their presence felt in this work, titled Welcome to the Broken Hearts Club. “I like having these different genres influence the rhythmic decisions, giving each movement a different feel,” she said.

Sometimes a stylistic reference helps communicate what the piece is about, as in the opening of her quintet. “The first movement bounces along in this meter that’s sort of cutesy,” she said. “I wanted to make it like a pop or a country song where the topic is something serious, but there’s a lightheartedness in the music.”

Genre plays a part in Barnes’ quintet as well, as she draws on R&B, jazz, pop, and gospel. But an even bigger emphasis is the philosophy of writing earworms. Not only do they have the benefit of “sticking the text to your memory,” she said, but also “bringing you back to the hall to hear it all again.”

She knows that some people would consider this too simple of a goal. “But I just feel that the classical community could benefit from the lack of complexity.” Plus, she said, the presence of an earworm doesn’t mean that the entire piece is simple. Complex harmonies and orchestration might well lie beneath a hummable tune.

As a vocalist herself, Barnes is not shy about her enthusiasm for composing vocal music. “I do write for instruments as well,” she said, “and that is a credit to my composition teacher from grad school, Dr. James Lee III. He understood that in today’s composition industry, versatility is really important for receiving commissions. And that’s allowed me to be a full-time composer now — it’ll be a year for me in June.”

The combination of voice and string quartet had a particular appeal to Meyer. “I’m passionate about creating a whole body of art song that doesn’t involve piano,” she said, noting the logistical hurdles the instrument can bring. “I like the idea that you could show up to someone’s home and hear music, and not need a piano.”

As a string player, she’s also keen on collaborating with vocalists. Sure, there’s opera, but in that setting “you’re a small cog in a large machine,” she said. “In this case it’s a collaboration of chamber music, so it’s extremely satisfying.”

Before writing for a singer, she makes a point of reaching out to talk. “I want to ask about their sweet spots and what to avoid,” she said. But she went a step further than usual with Chabrelle Williams, the program’s soprano. “I asked about her favorite lines of each poem and what kinds of sounds she hears at those parts. With that information, and knowing how I wanted to tone-paint the words, that’s where I was able to just get writing.”

~ ~ ~

Hashizume wouldn’t let it — though she was humble in telling me about the situation. “I started organizing porch-lessons and schoolyard group classes, because they had nothing to do, and I had nothing to do.”

That brought Hashizume even more face-to-face with the disparity between her own life experiences and those of her students and their families. It was heartbreaking for her. “And when I saw the poetry of Weatherspoon, it felt like he was speaking on behalf of the children in that neighborhood. It was so striking, so moving to me. My idea was just to bring light to these situations that many people are not aware of.”

She shared her thoughts with CityMusic executive director Eugenia Strauss. “She was very generous and empathetic, and connected me with the composers, who met on Zoom with Weatherspoon and with me. I think they did a wonderful job making the words into sound.”

As a violinist, Rychlik joined the Cleveland Musicians Union at age 14, traveled to Europe to study at the Prague Conservatory, and went on to perform with the Chicago Symphony, the Philharmonic String Quartet, and The Cleveland Orchestra.

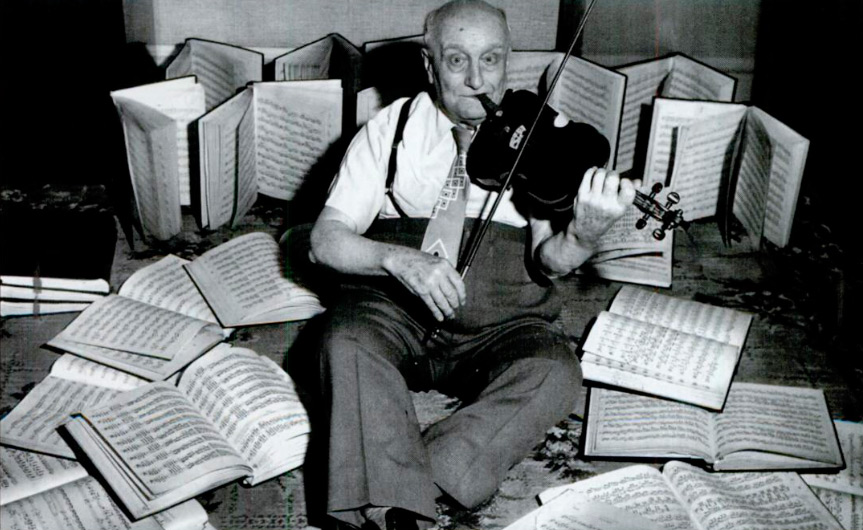

As a composer, he wrote largely for the violin, and as a violin teacher, his students numbered several hundred — 40 of whom went on to become members of The Cleveland Orchestra themselves. His pedagogy extended into scholarship with the 25-volume Encyclopedia of Violin Technique, written over a span of 20 years. (Pictured: Rychlik sitting with all 25 volumes, and certainly looking like he was enjoying himself.)

This weekend, Hashizume and Eric Wong will perform Rychlik’s Duo for Violin and Viola. She described his style as similar to that of Dvořák — “very accessible and beautiful, with lots of colors.”

In fact, Rychlik boarded in that composer’s home during those studies in Prague, and even helped Dvořák study English. So it only felt right to include some of his music as well: the Terzetto, where Hashizume and Wong will be joined by violinist Catherine Crosby (who has also become part of the teaching program in Slavic Village, Hashizume said).

One striking aspect of the Rychlik duo is its difficulty. “It’s the kind of piece that you wouldn’t play if you wanted a good review,” Hashizume said, laughing. “But I wanted people to know about it because it’s quite a piece. You can hear Rychlik’s personality in it — not at all ambitious, not trying to impress anybody, but just enjoying music in a very pure sense.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 6, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article