by Jarrett Hoffman

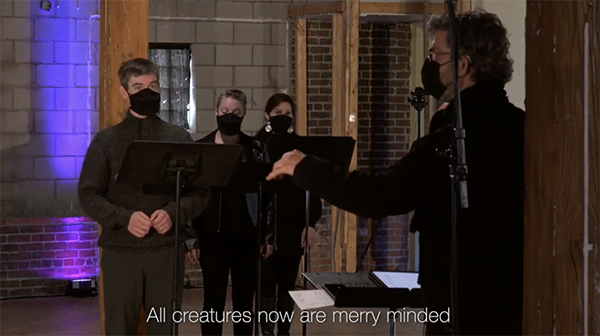

That’s exactly what Scott MacPherson and the Cleveland Chamber Choir did for the second performance of their sixth season. Masked and spaced several feet apart, the ensemble gathered for a recording session in the resonant space of a Train Avenue warehouse on Cleveland’s West Side last month. The resulting video — “Madrigals of All Times,” released on May 15 — is excellent in programming, performance, and production.

Two central threads run through MacPherson’s mosaic of madrigals: world premieres, and pairings of Renaissance and 20th-century pieces, which in several cases are set to the same text.

One such fascinating pairing comes in the second and third spots on the program. Vittoria Aleotti’s Io piano che’l mio pianto provides a prime opportunity to revel in the purity of Renaissance harmony, and in the Choir’s pure tone and intonation. Then, armed with the same text by Vincenzo Ruffo, Morten Lauridsen introduces more grit into the harmonic spectrum during “Io piano” from his Six Fire Songs on Italian Renaissance Poems. He also takes a more psychological approach to the subject of mourning, and that emotional depth is conveyed beautifully by both choir and conductor.

The premieres get underway with another Cleveland treasure: Dolores White, represented by her Three Madrigals. Addressing the subject of death with texts by John Donne and John Dowland, White traverses a variety of moods — peacefulness, playfulness, anger, sadness — but intriguingly, never settles firmly into any of them. The effect is otherworldly, as if some distant being is watching us all pass from one transient emotional state to the next.

Long thought to be lost, Adolphus Hailstork III’s Two Madrigals were only recently rediscovered. Thus the Choir delivers an uncommon type of world premiere — a first performance of a piece written decades ago, in this case while the composer was a student at Michigan State University. The second setting, “The Silver Swan,” shines in its striking use of canon, while “Cease Sorrows Now” closes with a compelling call-and-response on the word “farewell” as the Choir fittingly and skillfully dies away in volume.

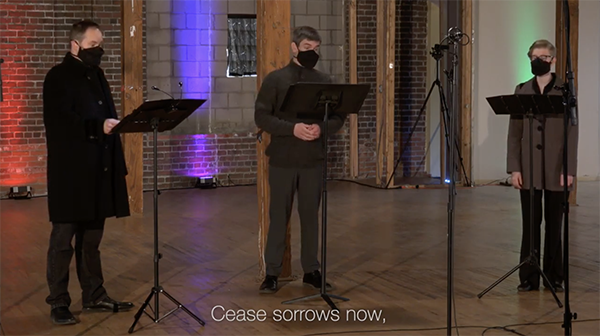

MacPherson has also programmed Renaissance settings by Thomas Weelkes and Orlando Gibbons of the same anonymous texts that inspired Hailstork. The Weelkes proves to be a particularly worthy addition. It whittles the Choir down to three members — Gwendolyn DeLaney, Joel Kincannon, and Paul Stewart — for an intimate and enjoyable performance only hampered by an imbalance that favors Kincannon and Stewart over DeLaney.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 26, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article