Jason Vieaux, guitar

by Daniel Hathaway

A strong, beautifully articulated reading of J.S. Bach’s “BWV 998,” three movements originally conceived for lute or harpsichord — or maybe Lautenwerk — showed Vieaux’s keen sense of structure and, in the fugue, his skill at layering voices.

An intermission interrupted Vieaux’s juxtaposition of Mexican composer Manuel María Ponce’s Sonata Mexicana with his Sonata Meridional, the first a popular work using real national tunes, the second a more formally conceived evocation of Spain. The guitarist brought out the innate flavor in each.

The high point of the program was Alberto Ginastera’s arresting Sonata, a work the guitarist recorded on Oberlin Records’ 100th anniversary tribute to the Argentine composer. Though Ginastera had always shied away from writing for the guitar, he gave in to a request from Carlos Barbosa-Lima in 1976, producing a concise but substantial work studded with special effects and echoes of Argentine folk music. Vieaux’s reading was assured and lively.

Argentine music ended the program as well, with two vibrant dances by Jorge Morel. A pair of encores (Vieaux said he thought it silly to keep leaving the stage) included a lullaby written by Chris Freitag after the birth of the Vieaux’s second child last year, and the guitarist’s own arrangement of Louis Armstrong’s What a Wonderful World. Playing on his home turf — he’s head of the guitar department at CIM — Jason Vieaux set a high bar for the rest of the Festival.

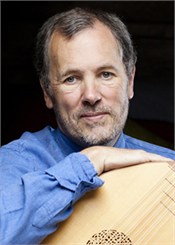

Nigel North, lute

by Samantha Spaccasi

A professor of lute at the Early Music Institute of Indiana University, North’s passion for the instrument and historical performance was evident in his playing and lengthy program notes, which provided detailed information about the selected pieces and the type of lute they would have been played on in Bach’s time. In between works, the affable North gave brief introductions to each of his selections to the audience’s enjoyment.

Adjusting his glasses, North opened the concert with the Suite in g, beginning the piece with a soft tenderness. The lutenist gradually increased the energy throughout the Suite, subtly bringing out emotion and color with each note. A less-experienced player might struggle with incorporating dynamic contrasts on Baroque lute, but North was able to make this and the challenging Suite in B-flat — the fourth suite for solo cello — sound multi-dimensional. He demonstrated exceptional phrasing on the first and second Bourrées. With his deep connection to his instrument and intuitive understanding of Bach, North completely revelled in the music.

After a brief intermission, the lutenist returned to the stage for the Sonata in g, originally written for solo violin. He played the piece beautifully, continuing to showcase his refined technique while exploring all corners of the Sonata for unexpected and beautiful aspects of the work. The musician then played the “Chaconne” from the Partita in d, also written for solo violin. This was a popular piece in the Festival — guitarist Hao Yang also performed it at her concert on Sunday afternoon. North played it with ease and enjoyment, as if he were speaking through his lute, bringing an informed perspective to his performance in Cleveland.

David Russell, guitar

by Mike Telin

Russell, who was making his debut at the Festival, begin by enticing the crowd with a bon-bon in José Brocá’s La Amistad (Fantasia in E), whose title means friendship. And his effortless technique, heartfelt musicality, and engaging repartee created the feeling of being in the company of friends at an intimate house concert rather than part of a crowd in a large venue.

Russell’s ability to create magic out of the simplest musical phrase or gesture was evident throughout his performances of the Partitas Nos. 1 and 2 by imaginative Baroque composer Johann Kuhnau.

A highlight of the evening came during the guitarist’s colorful and expressive performance of Enrique Granados’s Valses Poéticos. Performing it in honor of the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth, Russell exquisitely captured the melodic, noble, humorous, elegant, and sentimental qualities of each of its nine waltzes.

A second offering from the chocolate box came in the form of Domenico Scarlatti’s Sonatas K. 308 and 309, followed by Stephen Goss’s Cantigas de Santiago. Dedicated to Russell and his wife María, the work’s seven movements are based on 500-year-old songs and poems from the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. “One is about a monk who asks to view a little bit of heaven to see if it is worth so much suffering on Earth. Another is about a girl who plays her harp to the waves of the sea while waiting for her fisherman boyfriend to come home,” Russell told the audience. Goss provides a variety of moods, tempos, technical passages, and color palettes for the performer, which the guitarist brilliantly used to convey each story.

The gifted performer concluded his program with Francisco Tárrega’s spirited Gran Vals. But the audience was not going to let the evening end there, as they called Russell back to the stage for two encores, the first of which was Vincent Lindsey-Clark’s Shadow of the Moon.

Hao Yang, guitar

by Samantha Spaccasi

Performing from memory, Yang began Mauro Giuliani’s Grand Overture with confidence. Her deep passion for the music was evident on her face and in her body language — she bopped her head and leaned in close to her guitar while she played — and in her expressive phrasing and intelligent use of dynamics. It was thrilling to watch Yang’s dexterous fingers dance rapidly around the neck of her instrument. She handled the trickier passages of the piece with grace and style.

Though Yang seemed to be rushing through some pieces, she hit every single note while bringing color to each sound she made. She performed the chaconne from Bach’s Partita No.2, originally written for solo violin, with flawless technique, interpreting the piece intuitively and putting her unique spin on the work.

The highlight of the afternoon was her richly textured, electrifying performance of Isaac Albéniz’s Asturias, one of the most famous pieces in the classical guitar repertoire. Yang’s opening tremolos were barely perceptible at first, but she slowly built her volume, playing the first strum of the piece like a bolt of lightning striking a tree.

After a brief intermission, Yang returned to the stage greeted by a very excited audience. During Agustín Barrios’ Un sueño en la floresta, the guitarist switched from a delicate, soft whisper to thunderous playing in a matter of seconds, alternating docility and ferocity in her playing while maintaining a bright, clear tone. Her last selection, Antonio José’s Sonata para Guitarra, the only piece in the program written specifically for solo guitar, is also the composer’s only work for the instrument. José wrote the piece while Spanish Nationalists were persecuting their enemies, including the composer, and the pain of living under those forces is clear in the music. Yang translated that emotional intensity, bringing out the more devastating passages through tender, quiet playing.

After a well-deserved round of wild applause, Yang played an encore: Agustin Barrios Mangore’s Waltz No. 3. If Sunday’s performance was any indication, the young guitarist is destined for musical greatness.

Colin Davin, guitar, and Emily Levin, harp

by Timothy Robson

In spoken comments, the performers noted that there is very little repertoire composed especially for guitar and harp, despite the clearly felicitous combination of two plucked string instruments. Indeed, it was often difficult to distinguish which instrument was playing what.

The concert opened and closed with transcriptions by Davin and Levin of standard orchestral works. In between were two new works written for the Duo, including the world premiere of Dylan Mattingly’s La Vita Nuova (and other consequences of Spring).

Although Maurice Ravel’s Ma mère l’Oye, a suite of five pieces for piano-four-hands, was later transcribed for orchestra, the piano version served as the basis for this transcription. The transparency and delicacy of textures provided by the guitar and harp fit Ravel’s French Impressionism perfectly, especially in the softer passages. Only at the end of “The Fairy Garden” did the guitar struggle to match the grand crescendo of the harp. Here and throughout the program, the Duo’s ensemble and balance were well nigh perfect.

Will Stackpole’s ingenious Banter, Bicker, Breathe was a depiction of the phases of an interpersonal relationship in music — very busy, sometimes dissonant, and at other times calm and melodious. At times the guitar was called upon to bend the pitch of some notes. Altogether, it seemed as if there was more bickering and banter than breathing. Although Davin and Levin were up to the numerous technical challenges, there was rarely a sense of repose in the music.

Dylan Mattingly’s La Vita Nuova is hypnotically beautiful. The musical materials are minimalist — a series of ascending diatonic chords in the harp, answered by the guitar, become increasingly complex. A second section features gently rocking chords in the harp, with similar but more static harmonies. A sparse guitar line rises above the harp, occasionally ornamenting the beautiful melody. In the soft, slow, and improvisatory third section, arpeggiated chords between harp and guitar are slightly out of sync. A return to the opening music acts as a coda. This is an arresting work, and it was given a brilliant performance.

Manuel de Falla’s ballet suite El amor brujo closed the concert. Numerous transcriptions exist of the well-known “Ritual Fire Dance,” but the whole orchestral suite was quite successful in this reduction, in which the performers used many special effects and extended techniques.

Colin Davin and Emily Levin also offered an encore, their own transcription of Philip Glass’s Piano Etude No. 6. These talented performers prevailed against the fast tempo, rhythmic changes, and many repeated notes.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 15, 2017.

Click here for a printable copy of this article