by Jarrett Hoffman

Those two musicians will split the bill in a recital of solo music on Saturday, February 2 at 5:00 pm at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Cleveland. The event is part of the Cleveland Uncommon Sound Project’s free concert series, and includes a pre-concert chat at 4:00 pm.

There’s no more textbook “eureka” moment than when Brod, a member of Chicago-based Ensemble Dal Niente, happened upon Beth Lipman’s Laid Table (Still Life with Metal Pitcher) at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

During a recent phone call, Brod said it was “like getting hit in the head with something.” She had been thinking about a potential project and was trying to put it into words. “I turned the corner, and I was like, ‘Oh, everything makes sense now.’”

What would follow is a program titled “Memento Mori,” based on the theme of fleeting life that was common in several centuries of European religious art. A professional floral designer, Brod was used to thinking about decay. And as she said in an interview with Strings Magazine, “the images of blown-out and dying flowers in old still lifes really resonated.” Then, seeing Lipman’s “shockingly contemporary still life” helped her conceptualize how to rework old ideas “into something that speaks to our present time.”

“Memento Mori” includes four commissions, three of which will be performed in Cleveland: Alejandro Acierto’s Here, where we continually arrive, LJ White’s Look After You, and Lisa Atkinson’s (te) salve. Rounding out the program is Katherine Pukinskis’s 2015 Quiet Threnody, also written for Brod. (More on that piece in a moment.)

More than just an intriguing theme, “Memento Mori” also represents something very personal to Brod: a decision to expand her career into the solo realm. “For a very long time, I actually didn’t perform as a soloist at all,” she said. “It was never really where my tendencies had lain when I was a student. And the opportunity to play in an ensemble like Dal Niente was incredible — I loved working with everybody so much that I didn’t even try to move in that direction.”

“I thought about it for a little bit,” Brod said, “and ended up going for it. And we had just a fantastic time working together. We had so much fun, and it was really eye-opening for me to be a part of the creative process from that side. Obviously I’d premiered tons of pieces with Dal Niente, but I’d never been quite that involved in the process.”

Brod used that experience with Quiet Threnody as a springboard to performing solo sets in Omaha and at the International Computer Music Conference in Texas. “It helped me realize this was a direction I could go,” she said. “I felt fine — it didn’t make me super nervous or anything like that. But I kept thinking about what I went through with Kate and how much I enjoyed that. I wanted it to still be a collaborative process even if I was playing by myself.” She reached out to composers whose music she liked and who might be interested in that type of partnership. “And that’s where this program came from.”

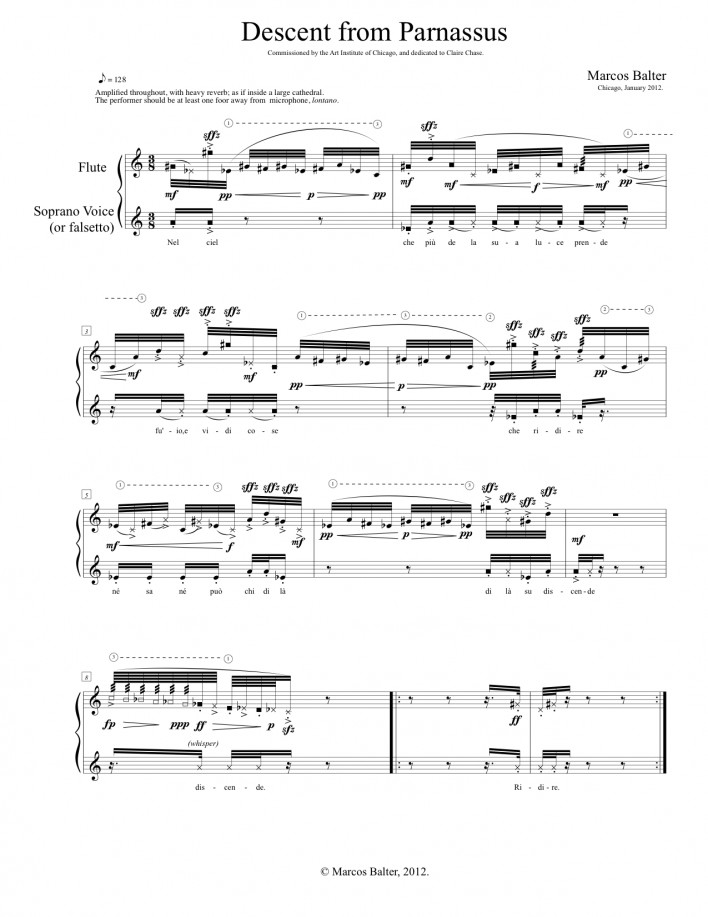

Interested in issues of identity, Cox is careful in his programming to highlight composers from communities underrepresented in classical music. In Cleveland he’ll perform Marcos Balter’s Descent from Parnassus, Felipe Lara’s Meditation and Calligraphy, Du Yun’s Run in a Graveyard, Eve Beglarian’s I will not be sad in this world, and Philippe Hurel’s Loops I.

Cox and I were able to get in touch over email. I asked about his musical interest in identity, which he linked to America’s political divide. “Now is the perfect time for artists to really speak out and be incredibly mindful of who to program,” he said.

Does Cox see progress in this area across the music world? “I think the industry is beginning to do an okay job with this, but as we see with many orchestras around the country, priority is given to pieces that have been played hundreds of times,” he said, citing composers like Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, and Brahms. While acknowledging that some of their works are indeed masterpieces, he asked, “Why not give more attention to music of our time, with emphasis on minority composers? There is constantly more work to do in this area.”

Another thread running through the program is use of the human voice. A good example is the Balter work, which requires the flutist “to speak/scream Italian text from Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, as well as play the incredibly difficult passages,” Cox said. “Since everything Marcos wrote isn’t all doable at once, the performer has a very hard decision of what to play, how to play it, and when to play.” What results is a fragmentation of both the text and the flute part, creating “an almost stuttering effect, which is very evocative of the text itself,” Cox added.

We closed by discussing how these composers experiment with silence. “The act of silence makes humans uncomfortable, because it actually makes us think,” Cox said. “Usually, audience members sit in their chair, listen, take in the music, and leave. But with these certain pieces, a majority of the time is given to this ‘act of silence.’ It makes the audience create their own experience/perception of the piece.”

Photos: Lipman sculpture courtesy of the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Balter score courtesy of the International Contemporary Ensemble.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 28, 2019.

Click here for a printable copy of this article