by Daniel Hathaway

Gazing at the skies, this is turning out to be a good day to enjoy some online performances from the comfort of your couch. Start at noon with South Africa’s Buskaid Soweto String Ensemble, hosted by the Princeton Symphony Orchestra (it’s available afterward on-demand).

This evening, the second episode in the Cleveland International Classical Guitar Festival features the CICGF debut of South Korean artist Ji Yeon (Jiji) Kim, and a performance by Dan Lippel of J.S. Bach’s “Lautenwerk” Suite on a guitar tuned to the composer’s favorite, non-equal temperament, Werckmeister III (read more about that mysterious subject in this preview.)

Later, Piffaro, the Renaissance wind ensemble, explores “Fuguing from Obrecht to Bach,” and the Philharmonic Society considers universal themes found in stories, legends, and myths with the assistance of guitarist Sergio Assad, vocalist Clarice Assad, and Chicago’s Third Coast Percussion.

Details in our Concert Listings.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

With regrets, we’ll pass over the birth of Irish lyricist Thomas Moore (born on this date in 1779, friend of Lord Byron, and admired by Robert Burns for his ability to adapt words to existing music like “The Last Rose of Summer,” and “Believe Me if all Those Endearing Young Charms,” later turned into “Fair Harvard” on the other side of the pond); and the deaths of Leopold Mozart, father of Wolfgang, in Salzburg in 1787; of Italian composer Luigi Boccherini in 1805 in Madrid; and of Czech composer Anton Reicha in Paris in 1836; and raise a glass to commemorate three other figures in music history.

Russian American conductor Nikolai Sokoloff, born in Kiev on this date in 1886, was tapped by Adella Prentiss Hughes to be the first conductor of The Cleveland Orchestra. At 13, Sokoloff moved to the U.S. with his family, studied at Yale and in Paris, and joined the Boston Symphony as a violinist at 17. He had returned from conducting the Manchester Orchestra in England in 1918 when he met Hugues in Cincinnati, “and was persuaded to accept a position from the Musical Arts Association to make a survey in Cleveland’s public schools and outline an instrumental music program. He accepted the position on the condition that he would be able to organize and conduct his own orchestra.” (Encyclopedia of Cleveland History)

And organize and conduct he did for the next 14 years, taking The Cleveland Orchestra on important national and international tours, developing educational programs, and initiating the recording and broadcasting of its concerts. The orchestra’s first commercial recording, made in New York on January 23, 1924 featured Tchaikovsky’s “1812” Overture in a much trimmed version that allowed engineers to fit the music onto 78 rpm discs.

His tenure was not without controversy. On April 29, 1926, the New York Times reported an incident that took place while the Orchestra was on tour to Dayton.

“The trouble began yesterday when Frank Venezzie, first trumpeter, was dismissed by the conductor.

“When I told Venezzie to play not so loud, he played three times louder,” Sokoloff explained. “I told him to play right or leave. He left.” …

Among those at practice was Morris Kirschner, first bassoonist, who said that Sokoloff insulted him. “He called me a dummy,” Kirschner said. “Is that any way to talk to an artist?”

“They think they will get me excited,” the conductor said today. “Do I look excited? I am as calm as a clam. There will be a concert if I have to go out and direct a program alone.”

Sokolowski’s influence on Cleveland continued even after he left town to direct the Federal Music Project in 1935, “channeling money into Cleveland for unemployed musicians, and providing the city with more opera and orchestral music than it had in many years.” (Encyclopedia of Cleveland History).

On this date in 1900, English musicologist Sir George Grove died in London at the age of 79. Trained as an engineer, Grove’s love for music got him appointed director of orchestra concerts for the Great Exhibition of 1851 at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London. He continued administering a concert series there after the building had been moved to Sydenham, and crafted admirable program notes for the benefit of amateur listeners. “I wrote about the symphonies and concertos because I wished to try to make them clear to myself and to discover the secret of the things that charmed me so; and from that sprang a wish to make other amateurs see it in the same way.”

One thing led to another, and Groves was invited by the publishers Macmillan and Company to produce a musical encyclopedia. Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians was eventually issued by Macmillan in alphabetical volumes over a dozen years, ending in 1889.

One of Grove’s passions was the music of Schubert, then little appreciated in England. He was instrumental in discovering the score and parts for the incidental music to Rosamunde, the 1823 play by Helmina von Chézy, during an exploratory visit to Vienna in 1867. In honor of that find, listen to a studio recording of excerpts from Rosamunde with George Szell and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra made in Amsterdam in December, 1957.

Grove ended his career as director of the refounded Royal College of Music. His Encyclopedia lives on — online.

Finally, Hungarian composer Gyorgy Ligeti was born on this date in 1923 in Dicsöszentmartin, Transylvania. One of the great innovators of the 20th century, he wrote music that is as attractive to the ear as it is challenging to the intellect.

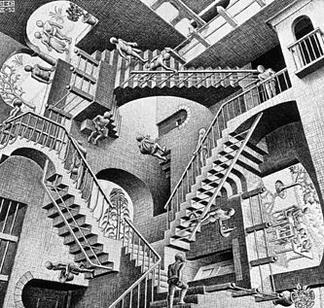

When I play Ligeti’s Étude No. 13: L’escalier du diable / The Devil’s Staircase, I have the feeling of climbing and of M.C. Escher’s endless staircases that Ligeti loved so much. I have the feeling not of looking at this famous architectural illusion, but of being part of it, and in vain of looking for an exit. And I feel deeply the existential dimension that this situation had for Ligeti.

Here’s Aimard’s elegant performance of No. 13, followed by a more athletic take on the work by Greg Anderson that includes arresting video effects.