by Jarrett Hoffman

HAPPENING TONIGHT:

At 7:30 pm, pianist Arsentiy Kharitonov plays music by Bach, Schubert, Schumann, Johann Strauss, Scriabin, and Rachmaninoff on the Rocky River Chamber Music Society series at Lakewood Congregational Church. It’s free. Read our interview with Kharitonov here.

IN THE NEWS:

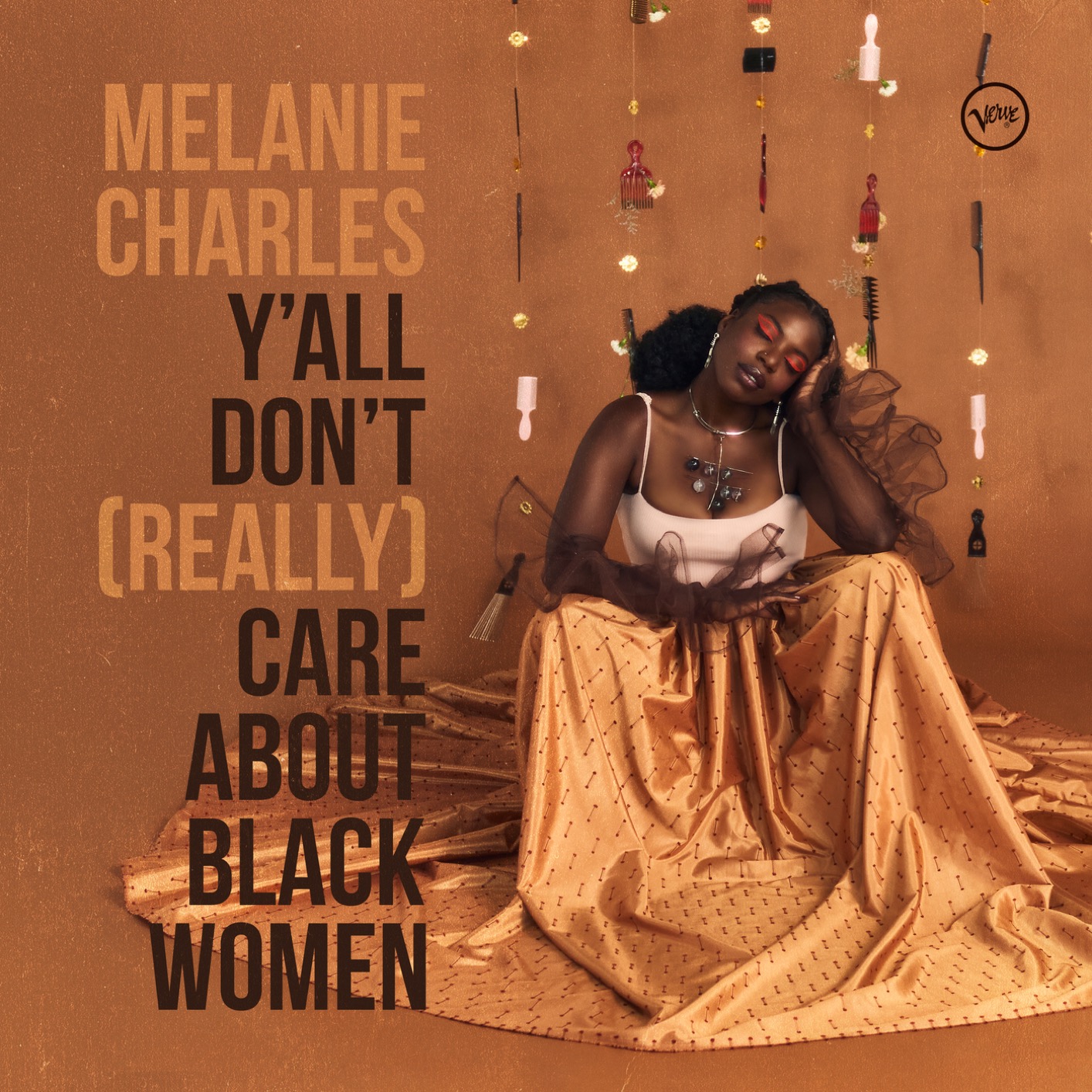

In The Washington Post, Shannon J. Effinger interviews flutist-vocalist Melanie Charles to talk about her unorthodox path to jazz, and her recent release Y’all Don’t (Really) Care About Black Women. The album, her debut for Verve Records, includes reimagined versions of music by such figures as Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Betty Carter, Dinah Washington, and Marlena Shaw. Another influence at play: the killing of Breonna Taylor.

“It’s not a secret that right now, people are waking up to the importance of the value of Black women across industries,” Charles tells Effinger. Read the article here, and listen on Spotify.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

“Brevig Mission is a tiny ocean-side settlement in Alaska which, in 1918, had 80 adult inhabitants. During the five-day period starting November 15, 1918, 72 of them were killed by the influenza pandemic then raging across the world.”

Thus begins an article by Ray Setterfield in On This Day about the 1918 pandemic.

72 out of 80 — that’s 90% of the town’s population. Horrifying. But there’s another reason why Setterfield highlights the settlement of Brevig Mission: its permafrost conditions meant that victims were not just buried but actually preserved, allowing scientists to study the virus decades later, determining its avian origins.

The article covers several aspects of that pandemic, from its multiple waves, to all the remedies that were promoted, to the restrictions on reporting its true impact, as several nations worried about lowering morale amidst World War I.

But the ending of the article — which was published on March 21, 2020 — hits the hardest of all.

“The question remains as to whether a devastating pandemic on the scale of 1918 could occur in modern times,” Setterfield writes. “Many experts think so.”

Then there’s the quote from Indiana University professor of medicine Richard Gunderman from a then-recent article in the Smithsonian Magazine: “As a society, we can only hope that we have learned the great pandemic’s lessons sufficiently well to quell the current Covid-19 challenge.”

…challenge.

Moving to musical anniversaries, on another day we might highlight figures such as German composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (died on this date in 1787), Argentine-born conductor Daniel Barenboim (who turns 79), and Hungarian-American conductor Fritz Reiner (died on this date in 1963).

Instead, I felt drawn to November 15, 1918 in particular, which saw the passing of Belgian composer Georges Antoine at 26. Of course, there were two tragedies of that time period, both easily able to take down a healthy young adult.

Having developed a damp-related fever from his time in the trenches of World War I during the cold winter of 1914-15, Antoine was hospitalized and ultimately discharged from the Belgian army. But he rejoined in 1918 amidst the push from Allied forces to win the war, and the condition returned.

A telegram to his mother read as follows:

“…[He] became aware of his situation but as he had already suffered so much during the war he did not believe in the seriousness of his illness. In the evening, about seven o’clock, he died quietly, without agony, speaking of his next return to Liège, his mother and the Prix de Rome…”

Head to YouTube to listen to his Piano Quartet in d, written in 1915-1916 during his time in Saint-Malo, France away from the conflict, or to Spotify to hear his A-flat-major Violin Sonata, begun in 1913 and also finished in 1915.