Pathways: Robert Cassidy, piano (MSR Classics).

From the first prelude to the last, Cassidy plays with a light touch, assured technique, and an expansive color palette. While no. 3, La Puerta del Vino (Mouvement de Habanera), is appealingly seductive, Cassidy brings a playfulness to Ondine (Water-Sprite) during No. 8. The pianist beautifully voices No. 10, Canope (Très calme et doucement triste), and the concluding Feux d’artifice (Fireworks) brings his performance to a flashy end.

Pathways opens with the enticing Barcarolle in F-Sharp, Op. 60 by Frédéric Chopin. Cassidy’s heartfelt account of the work takes listeners on a late-night ride on the Venetian canals.

Bookended by the Chopin and Debussy is Santa Barbara-based Joel Feigin’s Four Elegies for Piano: In memory of Renée Longy (1979, revised 1986). Written in honor of his ear-training teacher at Juilliard, Feigin’s piece is based on the pitches A and D, derived from his teacher’s nickname, ‘Mme. Re La.’

Feigin’s Four Elegies, all marked with slow tempos, could become monotonous in the hands of other pianists, but Cassidy’s insightful approach to the work immerses one in an imaginative tonal world. — Mike Telin

Caroline Oltmanns: Venezia e Napoli. Caroline Oltmanns, piano (Filia Mundi).

Oltmanns, who recorded the album in Hamburg on a German Steinway, renders Debussy’s watercolors and textures with evocative brushstrokes, captures the spirit of a baroque sarabande in the “Hommage à Rameau,” and spins “Mouvement” out with a dizzying clarity. Her playing of Liszt’s memoirs — each movement based on a song with connections to Venice or Naples — is stylish and well-controlled. The Haydn is a model of lucidity, and Oltmanns makes a complete little picture out of each of Beethoven’s witty “trifles.”

This is a fun album of contrasting pieces that share a certain metaphysical connection. Oltmanns manages to connect with the listener via a recording as successfully as she does in her live performances. The liner notes are crisply written and the photos are lovely. — Daniel Hathaway

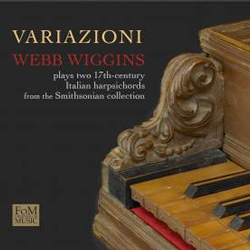

Variazioni: Webb Wiggins plays two 17th-century Italian harpsichords from the Smithsonian collection (Smithsonian Friends of Music).

The instruments we hear are, in order of appearance, a three-register instrument (two sets of strings at unison pitch, one an octave higher) made by Nicolaus DeQuoco in Florence in 1694, and a two-register harpsichord (both sets at unison pitch) fashioned by Giovanni Battista Giusti in Rome in 1693 — two of some fifteen old Italian instruments in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. Housed in thin, cypress wood cases, the harpsichords were meant to be stored and carried about in sturdier, outer cases and taken out and placed on stands when they were played. Both have a colorful, fundamental sound. It’s difficult to tell them apart except when the DeQuoco’s octave register is brought into play.

Wiggins’s fluent fingerwork, sensitive touch, and expressive pacing distinguish the two toccatas and the string of variations, dances, and passacaglias. And who doesn’t love variations? Even if the tunes are unfamiliar, they stick in the ear very quickly. Informative notes by Oberlin musicology professor Steven Plank and detailed descriptions of the instruments by Smithsonian curator Kenneth Slowik provide background for those who want to delve more deeply into the repertoire and the harpsichords featured on this fine recording. — Daniel Hathaway

The Organ Music of Gerre Hancock: Todd Wilson, organist, with Kevin Kwan, organ (Raven).

Todd Wilson, who directs the music at Trinity Cathedral in downtown Cleveland, encountered Gerre Hancock while he was studying at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music and Hancock was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church Cathedral. As a memorial to his mentor, who died in 2012, Wilson spent three days at St. Thomas in August 2013 recording all of Hancock’s organ music. The result is a handsome, 2-CD set chock-full of preludes, fugues, and variations on hymn tunes, fanfares, liturgical meditations, a three-movement Holy Week Suite for two organs, and a Fancy for Two to Play (organ duets intended for Hancock and his wife Judith, here played by St. Thomas assistant and Wilson’s former CIM student Kevin Kwan).

Lovers of the French organ and English cathedral music will luxuriate in these recordings. Wilson plays Hancock’s works lovingly, fastidiously, and thrillingly, as though channeling the master himself. The extensive documentation features photos of Gerre Hancock at various stages of his life, and a history of the organs of St. Thomas Church. — Daniel Hathaway

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 17, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article