by Neil McCalmont

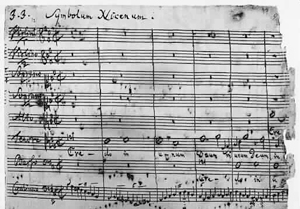

The work’s history is complicated, as Bach originally wrote the “Kyrie and Gloria,” “Sanctus,” and “Crucifixus” earlier in his career for different purposes. Though the composer was nearly blind in his last years, he revised these movements accordingly and completed the work in 1749, only a year before his death. His motivation has baffled scholars for centuries: why would a devout Lutheran complete a Catholic mass setting, especially at the end of his life? BPI Artistic Director Kenneth Slowik suggested one hypothesis during a recent telephone call. “Bach was aware of the long tradition of Catholic church music, exemplified by his use of cantus firmus, so he was being practical in order to get the work performed.”

If so, Bach’s attempt at practicality backfired. The whole mass was never performed during Bach’s lifetime. It took his son, composer Carl Philipp Emanuel (of greater contemporary fame than his father), to resurrect the “Credo” in 1786, and various parts of it were revived through the early 19th century. Not until 1859, over a century after the composer’s death, was it played in full. Despite the scarcity of performances, it still had a remarkable influence on the composers of this time. “Haydn studied it intently, and Beethoven desperately tried to obtain a score,” Slowik explained.

But its story does not end there. In 1981, at a meeting of the American Musicological Association, Joshua Rifkin proposed that, rather than a full chorus, Bach’s Mass was originally intended for one-singer-per-voice-part. Some found this so outrageous that a brawl ensued, though it was not the first time violence had been inspired by Bach, and probably not the last. This performance practice, however, has garnered a respectable reputation and become more commonplace.

Slowik has even performed this version with Rifkin a number of times. He suggested that the intimate setting allows for greater nuance and clarity, and for the instruments to blend with the voices more effortlessly, “without ever losing its power or effect.” Slowik and longtime BPI harpsichordist and Oberlin professor Webb Wiggins performed this version of the “Credo” in 2014 at the Oberlin institute (pictured above), and more recently, the entire work at the Sweetwater Festival in Owen Sound, Ontario.

“It’s actually my fault we’re doing this performance of the Mass,” Wiggins said, laughing, over the phone. “It’s a chamber concept, it’s intimate and transparent. It could even be done without conducting.” The harpsichordist has been part of BPI for about forty years, “I think I’ve only missed two summers since about 1975. I first came here as a student, then I was a staffer. Sometime afterward I became a faculty member and thought ‘I get paid to do this?’”

All of the singers for this rendition are Oberlin alumni, an idea also spearheaded by Wiggins, who has worked with them previously. “The Baroque Performance Institute is a family, it has nothing to do with blood, but everything to do with the musicians.”

Soprano Molly Netter, Oberlin class of 2010, started her BPI career singing Monteverdi’s Vespers. “It’s truly an honor and joy,” she raved about her experience. “I love coming back to Oberlin, I would never have gone anywhere else. The people at BPI are there for the joy of the music.” Concerning the piece, Netter admires how Bach conveys the drama of the text in his music, similar to the two Passions. “Every time you pick up a new piece of Bach’s, you learn something new about him, and with the one-on-a-part version, it allows the voice to express a linear idea.”

“The faculty are just amazing,” said countertenor Nathan Medley, Oberlin class of 2009. “Slowik and Wiggins are both such seasoned teachers.” When asked about the one-on-a-part version, he replied excitedly, “The singers will be able to interact with each other and with the instrumentalists much more closely, it allows us to shape our phrasing in the same way.” As an experienced singer who works primarily in the early music and contemporary repertoires, Medley stated that he is particularly looking forward to this experience with Bach’s b minor Mass.

The Oberlin Baroque Performance Institute has been an oasis for students of early music for decades. The enthusiasm, dedication, and musicianship of the faculty and students are remarkable, and undoubtedly will contribute to a riveting performance of this masterpiece. But even with all of the scholarship to draw from, there are still many unanswered questions about the Mass in b minor. What would Slowik ask Bach if he had the opportunity to sit down with the composer over a beer? “I would be in such abject admiration that I wouldn’t be able to stutter a word.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 26, 2016.

Click here for a printable copy of this article