by Jarrett Hoffman

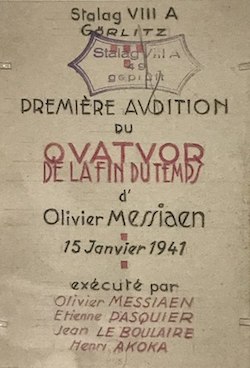

You can’t overstate the contrast in time and place between that barrack at Stalag VIII-A in Görlitz, Germany, 1941, and Reinberger Chamber Hall at Severance Hall in Cleveland, Ohio, 2018. But perhaps the two settings will be linked by some small thread on Friday, June 29 at 7:30 pm, when Reinberger plays host to ChamberFest Cleveland’s concert titled “Behind Bars” — and four performers close out the evening by contending with those marks on paper that comprise Quartet for the End of Time.

Taking on that eight-movement work will be violinist Noah Bendix-Balgley, clarinetist Franklin Cohen, cellist Julie Albers, and pianist Roman Rabinovich. I reached the string players and pianist by phone and by email to talk about a few specific movements and how they plan to interpret the work as a whole. Selections from our separate conversations are presented here in a roundtable format.

Mvt. 1: Liturgie de cristal – for full ensemble

Julie Albers: I love the sound world that Messiaen creates. You really can hear birds in the timbre and rhythms.

Rabinovich: In the piano part, the same notes keep circling back in these patterns of rhythm which start and end at different places. It’s fascinating to watch how it all connects while you’re playing. It’s such coloristic music — quite stunning.

Mvt. 5: Louange à l’Éternité de Jésus – for cello and piano

&

Mvt. 8: Louange à l’Immortalité de Jésus – for violin and piano

Noah Bendix-Balgley: One of the things that Messiaen is known for — and which happens in the solo violin and cello movements — is this “end of time.” In the violin movement, I think he asks for a tempo of eighth note = 36, so my part is only a page of music, but it’s about ten minutes long. In this way, he changes the performer’s and the audience’s perception of how quickly time is passing. Every beat has a different chord played twice by the piano.

Rabinovich: I think this figuration in the piano is definitely a heartbeat.

Rabinovich: The piece ends in such a moving way. It’s this angel that takes you up to the sky.

Bendix-Balgley: And it’s a real challenge technically for your control of the instrument — sound control, control of what kind of colors you’re producing, and muscle control as well, because you have to pull the bow at such a slow pace and still maintain musical tension, direction, and line.

Albers: He seems to be experimenting with great contrast throughout the work, and I find the cello and violin movements to be two of its most transcendent moments. They are completely different from everything else, and feel so related to each other that they really bring the piece together as a whole.

Mvt. 6: Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes – for full ensemble

Rabinovich: The sixth movement is probably the most famous. It comes from his fascination with Indian classical music and the rhythmic patterns of ragas. It’s all in unison and so complex rhythmically that it’s very, very tricky to feel it completely together and breathe as one organism. But once you get it, it’s so thrilling to play. It’s like an ecstatic dance — you just completely surrender.

Closing thoughts

Jarrett Hoffman: As a performer, how much do you weigh the historical and programmatic aspects of the piece versus what you see on the page?

Bendix-Balgley: I always approach things first from the notation. My job as an interpreter is to try to realize what information the composer has given in terms of dynamics, articulation, intervals, and the interplay between the different instruments. Later on, when you’re looking at the piece overall, you can start to think more architecturally about how one movement goes into the next. Of course, it’s important for us as interpreters to know the background of the composer’s life and the programmatic elements of a piece like this. That can affect some of what we want to communicate to the audience.

Albers: Knowing the story adds a gravity to the piece that is hard not to think about when you are playing it. It also adds a power when you think about the circumstances under which it was created and premiered. I think the quote from Messiaen was, “Never was I listened to with such rapt attention and comprehension,” referring to the first performance, which shows the ultimate power and connection that music has and creates. To feel heard and understood while being in a Nazi POW camp is unfathomable under any other circumstance.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 25, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article