by David Kulma

In the ‘30s, Aaron Copland was an unabashed leftist, going so far as to make a speech at a Communist party political rally, so it’s not surprising that his enigmatic Statements from 1935 gives off political whiffs. The work bridges the gap between the composer’s crunchy modernism of the ‘20s and open-spaced populism of the ‘40s with an emphasis on strangely beautiful counterpoint. In an interesting surprise, Copland alternated between the innocuous and the political in giving titles to the short, inconclusive movements. While “Subjective” ushers the strings through abstractly poignant lines with wide leaps, the politically-tinged “Jingo” invokes a madcap, sarcastic carnival — and elicited chuckles from the audience as it flitted away. Perruchon deftly led the Orchestra through a percolating reading of this purposefully obscure, yet pointed music.

Carl Orff also started off as a leftist in Weimar Germany, but as Hitler rose, the composer compromised his beliefs to protect his composing career, his excellent children’s music education programs, and his family. Premiered in 1937, Carmina Burana is a celebration of humanity framed by the famous, fateful prologue “O Fortuna.” Immensely popular at its debut, this secular cantata on medieval texts found in a Bavarian monastery originally bothered the Nazis, who eventually came around after realizing they couldn’t contain its success. And no wonder: Orff managed to create a show-stopping hour of magnificent earworms toggling through Stravinskyan rhythmic pounding, bawdy pub tunes, and Puccinian love songs complete with a lofty coloratura soprano.

During the 25 short movements, The Cleveland Orchestra showed sparkling shine, menacing power, and dancing spectacle. Taking a few notably quick tempos. Perruchon brought an energetic air to the proceedings, and managed the huge forces with ease. Tenor Matthew Plenk’s pleading swan in “Olim lacus colueram” was splendidly forlorn, while soprano Audrey Luna’s melisma in “Dulcissime” was heart-stopping. But baritone Elliot Madore stole the evening with his gorgeous, lovestruck high notes in “Dies, nox et omnia” and his hysterically funny portrayal of a drunken abbott in “Ego sum abbas Cucaniensis,” abetted by Perruchon as the straight man.

The Cleveland Orchestra Children’s Chorus, prepared by Ann Usher, sparkled innocently. And starting with explosively clear consonants in the opening prologue, Lisa Wong’s Blossom Festival Chorus gave love-filled performances of the sixteen numbers they anchored. In the end, Carmina Burana is a showpiece for chorus, and it succeeds in performances like this one, which was full of great choral singing. It’s impossible not to get caught up in this pageant of joy, sex, drink, and the hammer blows of fate — or to escape the discomfort that comes with knowing its political history.

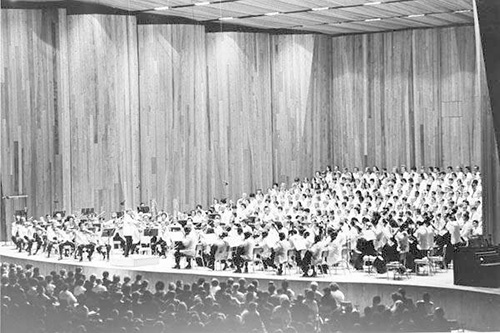

1968 Carmina Burana photo courtesy of the Cleveland Orchestra Archives. 2018 photo of the Blossom Festival Chorus by Roger Mastroianni.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com August 28, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article