by Jarrett Hoffman

MCGILL ON COLERIDGE-TAYLOR

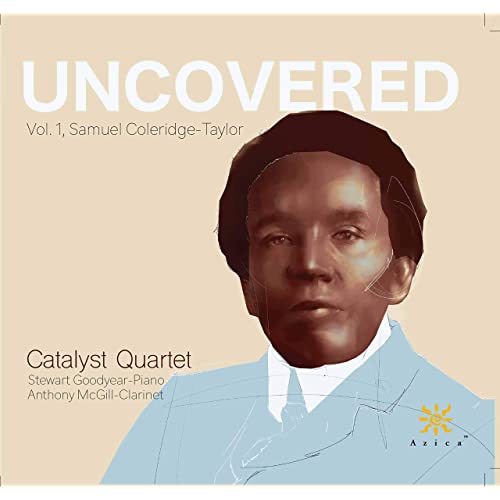

Earlier this month, VAN Magazine published a fascinating interview between Brin Solomon and clarinetist Anthony McGill centered around Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. That composer’s music is the focus of the new album Uncovered, Vol. 1 from the Catalyst Quartet, McGill, and pianist Stewart Goodyear, released on Azica Records.

Solomon and McGill discuss how racism impacts which historical figures we do and don’t learn about. “It’s whitewashing history: We don’t find out about all the heroes and creators that are of African descent,” McGill says.

The clarinetist also shares his own personal feelings about playing Coleridge-Taylor’s Clarinet Quintet. “It sounds like the experience of someone I can identify with, someone who’s a Black man,” McGill says. “Those melodies are singing to you directly, whoever you are. But also, as I was playing them, I felt like they were coming directly from me.”

Among many other topics, Solomon and McGill also consider the question of whether classical music institutions are making meaningful change with regards to diversity and changing the power structures within the field.

Listen to McGill and the Catalyst perform the first movement of Coleridge-Taylor’s Clarinet Quintet on YouTube. Also, stay tuned for a live performance of the piece on April 11 from CityMusic Cleveland.

TODAY ON THE WEB:

Today, Apollo’s Fire will release the concert video of “Tapestry: Jewish Ghettos of Baroque Italy,” an exploration of the vibrant melting pot of Jewish culture in Italy c. 1600. Purchase tickets here — the video will be available on-demand for 30 days.

Other local attractions include “CIM Perspectives: Armenian Music for Peace” at 7 pm (free, but donations benefit humanitarian relief for Armenia and Artsakh) and WCLV’s “Cleveland Ovations: The Best of BlueWater Chamber Orchestra” at 8 pm.

Moving southwest, the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music welcomes Transient Canvas in a virtual residency tonight and tomorrow, both at 7:30 pm, including six premieres by CCM students (watch here). And moving east, the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society presents pianist Richard Goode at 6:00. A bit further east, the Philharmonie de Paris presents Ensemble Intercontemporain at 2:30.

Details in our Concert Listings.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

The two most famous musicians to recognize today are Austrian composer Joseph Haydn (born on this date in 1809) and Polish violinist/composer Henryk Wieniawski (died on March 31, 1880). But let’s instead turn our focus to a pair of lesser-known figures, beginning with an Ohio-connected composer.

Jake Heggie was born on this date in 1961 in West Palm Beach, Florida, but shortly afterward, his family moved to Columbus, Ohio, where he was raised. Heggie’s story clues you into the amount of creative talent that exists in the administrative sector of the arts industry: in the late ‘90s, he went straight from the position of public relations associate for San Francisco Opera to being named that company’s composer-in-residence. His international career began with Dead Man Walking, premiered in 2000. Watch a clip from a 2016 performance by Shreveport Opera here.

And soprano Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, who died on March 31, 1876, was considered the best-known Black musician of her time in both Europe and America, armed with a beautifully resonant voice and a wide range. Born into slavery in Natchez, Mississippi, she was taken to Philadelphia as a child and freed, though she continued to serve her former mistress until that woman’s death. After that, Greenfield supported herself by performing, gained recognition in the Northeast, and eventually embarked on a tour of the U.S. and Europe that included performing for Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace.

That description covers the basic facts about her life and accomplishments, but there is so much ugliness that’s also important to understand in the history around Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield. Learn about the different ways in which racism impacted her career in an article by Adam Gustafson in The Conversation, which ends on a positive note about her impact on society:

But Greenfield’s tour did more than prove to white audiences that black performers could sing as well as their European peers. Her tour challenged Americans to begin to recognize the full artistry – and, ultimately, the full humanity – of their fellow citizens.