By Mike Telin and Daniel Hautzinger

It’s a phrase emblematic of Hinton’s approach to life: laid-back, optimistic, and warmly human. These are the qualities that were emphasized over and over again on Thursday, June 12, in Oberlin during a day celebrating the life and legacy of Milt Hinton.

Hinton left behind a three-fold legacy: aural, visual, and human. He lives on in nearly 1,200 recordings, in his 60,00 photographs of musicians, and in the many young musicians he mentored and taught. Some of these legacies now reside at the Oberlin Conservatory, which has been gifted The Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Papers, four of Hinton’s basses, and the $250,000 Milton J. Hinton Scholarship Fund, established in 1980 by friends and family of Hinton on the occasion of his 70th birthday. This new partnership with the Hinton estate was facilitated by Oberlin Professor of Jazz Studies and Double Bass Peter Dominguez and Special Collections Librarian Jeremy Smith.

The afternoon began at 2:30 when Jeremy Smith welcomed a larger-than-anticipated crowd who had gathered in the Conservatory lounge, where an exhibit of Hinton’s photographs entitled The Way I See It was on display. [Read more…]

If Igor Stravinsky were alive today, he would probably get along quite well with the kind of people who live in Brooklyn, sport wispy facial hair, don ugly-patterned sweaters, and qualify their interests and appearance as “ironic.” For irony seemed to be intrinsic to Stravinsky, especially once he entered middle age and began co-opting other styles of music, from Baroque to jazz. Parody is particularly evident in his solo piano works, recently recorded by Jenny Lin for the Steinway & Sons label.

If Igor Stravinsky were alive today, he would probably get along quite well with the kind of people who live in Brooklyn, sport wispy facial hair, don ugly-patterned sweaters, and qualify their interests and appearance as “ironic.” For irony seemed to be intrinsic to Stravinsky, especially once he entered middle age and began co-opting other styles of music, from Baroque to jazz. Parody is particularly evident in his solo piano works, recently recorded by Jenny Lin for the Steinway & Sons label. Nineteen-year old violinist Chad Hoopes is certainly not the first young violinist to play the Mendelssohn concerto. (Hoopes himself first performed it with a professional orchestra when he was nine). As Donald Rosenberg notes in his well-researched liner notes for Hoopes’s new recording of the concerto, it was written for Ferdinand David, who began his career as a prodigy, and it was later taken up by the great 19

Nineteen-year old violinist Chad Hoopes is certainly not the first young violinist to play the Mendelssohn concerto. (Hoopes himself first performed it with a professional orchestra when he was nine). As Donald Rosenberg notes in his well-researched liner notes for Hoopes’s new recording of the concerto, it was written for Ferdinand David, who began his career as a prodigy, and it was later taken up by the great 19

Erich Wolfgang Korngold isn’t exactly a household name, but you’ve probably heard music by him or imitating him. Korngold, an Austrian composer active in the first half of the twentieth century, is best known in the US for his scores of such Hollywood films as The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Prince and the Pauper in the ‘30s and ‘40s. As the distinguished music journalist Donald Rosenberg said in a phone interview, “He really changed the whole trajectory of film scores by writing very lushly for the orchestra, using it almost as a character in the drama, and by writing scores that were essentially operatic, with themes for different characters.”

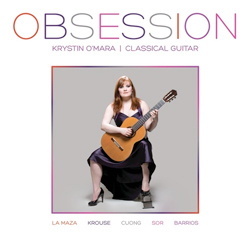

Erich Wolfgang Korngold isn’t exactly a household name, but you’ve probably heard music by him or imitating him. Korngold, an Austrian composer active in the first half of the twentieth century, is best known in the US for his scores of such Hollywood films as The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Prince and the Pauper in the ‘30s and ‘40s. As the distinguished music journalist Donald Rosenberg said in a phone interview, “He really changed the whole trajectory of film scores by writing very lushly for the orchestra, using it almost as a character in the drama, and by writing scores that were essentially operatic, with themes for different characters.” On her debut solo album, Obsession (Blue Point Studios Label), young classical guitarist Krystin O’Mara firmly establishes herself as “someone to watch.” Her performances of works by Regino Sainz de la Maza, Ian Krouse, Viet Cuong, Fernando Sor and Augustin Barrios Mangore are truly impressive.

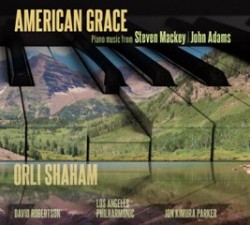

On her debut solo album, Obsession (Blue Point Studios Label), young classical guitarist Krystin O’Mara firmly establishes herself as “someone to watch.” Her performances of works by Regino Sainz de la Maza, Ian Krouse, Viet Cuong, Fernando Sor and Augustin Barrios Mangore are truly impressive. Of all instrumentalists, pianists seem to commission and perform new works the least often. The repertoire for the piano is already so vast and worthy that many performers see no need to add to it. Why even play pieces from the past half-century, when there is so much great, neglected, earlier music?

Of all instrumentalists, pianists seem to commission and perform new works the least often. The repertoire for the piano is already so vast and worthy that many performers see no need to add to it. Why even play pieces from the past half-century, when there is so much great, neglected, earlier music? The

The