by Stephanie Manning

The Oberlin-Como Piano Festival begins tonight at 7:00, presented online as part of Oberlin’s Stage Left Series. The Day 1 program, Piano Concerti of Beethoven and Brahms, will include an interview with Yefim Bronfman followed by performances and master classes with Anastasia Vorotnaya, Xiaoyu Liu, Leonardo Pierdomenico, and Yangrui Cai. Tune in here, and learn more about the festival in this preview article.

And at 8:00 in Cleveland Heights, Apollo’s Fire will feature harpsichordist Jeannette Sorrell and violinists Olivier Brault, Alan Choo, and Emi Tanabe in an energetic program of Bach, Vivaldi, and Telemann. Tickets are available here.

IN THE NEWS:

The Cleveland Institute of Music is welcoming three new members to the conservatory faculty (pictured). They are violinist Philip Setzer of the Emerson String Quartet and two Cleveland Orchestra musicians: assistant concertmaster Jessica Lee and principal horn Nathaniel Silberschlag. All are recruiting students for 2022-23, and Silberschlag will co-teach with CIM’s head of the horn department and Cleveland Orchestra principal horn emeritus, Richard King.

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg was obsessed with the number thirteen — notable, then, that he died on this day in 1951, a Friday the 13th, at the age of 76 (7+6 = 13). For a concise introduction to his life and works, check out this ten-minute YouTube video by Samuel Andreyev.

Schoenberg is best known for his use of a compositional technique called twelve-tone serialism, which can create a dissonant or “scary” sound. Learn more about this system and its evolution in this article in The New York Times. Even before he finalized the technique, Schoenberg embraced atonality in his earlier works, such as Pierrot Lunaire. Listen (and watch) a fantastic performance by the Israeli Chamber Project on YouTube here.

Despite Schoenberg’s lasting association with serialism, many of his works also incorporated classical forms and techniques. A great example is his Piano Concerto, which soloist Kirill Gerstein performed with The Cleveland Orchestra in 2017. In our preview for that performance, we interviewed Gerstein, who explained that “there’s a lot of dance in the concerto. There’re some waltzes, some gavottes, and some marches — really traditional musical references.”

The Cleveland Orchestra will perform Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto again on February 24-26, 2022 — this time with pianist Mitsuko Uchida. Franz Welser-Möst will conduct the program, which also includes Brucker’s Symphony No. 9.

Just like Schoenberg’s music itself, the story behind the Piano Concerto is complicated. He was commissioned to write it by one of his students at UCLA, Oscar Levant, who thought it would be a short composition — but Schoenberg fleshed it out into four movements, charging Levant an exorbitant sum which he then refused to pay. Though Levant eventually relented, it was another student of Schoenburg, Eduard Steuermann, who premiered the work in 1944.

And on this date in 1762, Benjamin Franklin announced the creation of a new instrument (pictured). Inspired by the sounds produced by swirling a wet finger around the rim of a wine glass, Franklin worked with a glassmaker to create a series of spinning glass bowls he named the armonica. The instrument became so popular that it was featured in compositions by Beethoven, Mozart, and Donizetti, but it was largely forgotten by the 1820s.

Franklin ultimately made no money from the construction of more than 5,000 armonicas, because he refused to patent or copyright any of his inventions. He explained the reason why in his autobiography:

“As we enjoy great Advantages from the Inventions of others we should be glad of an Opportunity to serve others by any Invention of ours, and this we should do freely and generously.”

It was March 20, 2020, when The Cleveland Orchestra and Franz Welser-Möst gave their last concert as a complete ensemble before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down live performances for more than a year. The Orchestra, with guest conductor Brett Mitchell, returned triumphantly to Blossom Music Center on July 3 and 4 to celebrate Independence Day. I attended on July 4.

It was March 20, 2020, when The Cleveland Orchestra and Franz Welser-Möst gave their last concert as a complete ensemble before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down live performances for more than a year. The Orchestra, with guest conductor Brett Mitchell, returned triumphantly to Blossom Music Center on July 3 and 4 to celebrate Independence Day. I attended on July 4. “What a year!” Kent Blossom Music Festival director Ricardo Sepúlveda said in a recent telephone conversation. “But we’ve been fortunate. The challenges of the pandemic provided us with opportunities to learn, to explore, to be creative and innovative, and how to adapt to rapid change.”

“What a year!” Kent Blossom Music Festival director Ricardo Sepúlveda said in a recent telephone conversation. “But we’ve been fortunate. The challenges of the pandemic provided us with opportunities to learn, to explore, to be creative and innovative, and how to adapt to rapid change.” What has happened to June? The sudden flood of openings and return to in-person performances has made the month fly past, but also left some unfinished business — like a review of The Cleveland Orchestra’s In Focus Episode 12, subtitled “Celestial Serenades” that features works by Aaron Jay Kernis and Josef Suk.

What has happened to June? The sudden flood of openings and return to in-person performances has made the month fly past, but also left some unfinished business — like a review of The Cleveland Orchestra’s In Focus Episode 12, subtitled “Celestial Serenades” that features works by Aaron Jay Kernis and Josef Suk. Both considered young musical prodigies, composers Edvard Grieg and Erich Wolfgang Korngold enjoyed great successes in their careers. But while works by Grieg have long been part of the standard orchestral repertoire, Korngold’s film scores have overshadowed his classical compositions until more recently. The 13th episode of The Cleveland Orchestra’s digital series In Focus, “Dance & Drama,” presents works for string orchestra from each composer to highlight their shared Romantic sensibilities and influences from other art forms.

Both considered young musical prodigies, composers Edvard Grieg and Erich Wolfgang Korngold enjoyed great successes in their careers. But while works by Grieg have long been part of the standard orchestral repertoire, Korngold’s film scores have overshadowed his classical compositions until more recently. The 13th episode of The Cleveland Orchestra’s digital series In Focus, “Dance & Drama,” presents works for string orchestra from each composer to highlight their shared Romantic sensibilities and influences from other art forms. The name Florence Price had barely come up in school. So in 2016, when pianist Michelle Cann was asked to play that composer’s

The name Florence Price had barely come up in school. So in 2016, when pianist Michelle Cann was asked to play that composer’s  At more than 200 schools across Ohio, students from pre-K to twelfth grade can start their day feeling calm and relaxed thanks to three minutes of classical music. Developed by local non-profit organization The Well, the Mindful Music Moments program pairs audio prompts with performances by local orchestras to increase student focus and reduce anxiety. This year, the program partnered with The Cleveland Orchestra, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, and the Columbus Symphony to create a piece directly inspired by the kids of Mindful Music Moments and the cities they call home.

At more than 200 schools across Ohio, students from pre-K to twelfth grade can start their day feeling calm and relaxed thanks to three minutes of classical music. Developed by local non-profit organization The Well, the Mindful Music Moments program pairs audio prompts with performances by local orchestras to increase student focus and reduce anxiety. This year, the program partnered with The Cleveland Orchestra, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, and the Columbus Symphony to create a piece directly inspired by the kids of Mindful Music Moments and the cities they call home. In Episode 6 of the

In Episode 6 of the  Full-length symphony orchestra concerts normally feature three works and run nearly two hours including intermission. The pandemic, which has changed so many things, has truncated programs, both to shorten possible exposure time and to avoid the social mixing of a mid-concert interval.

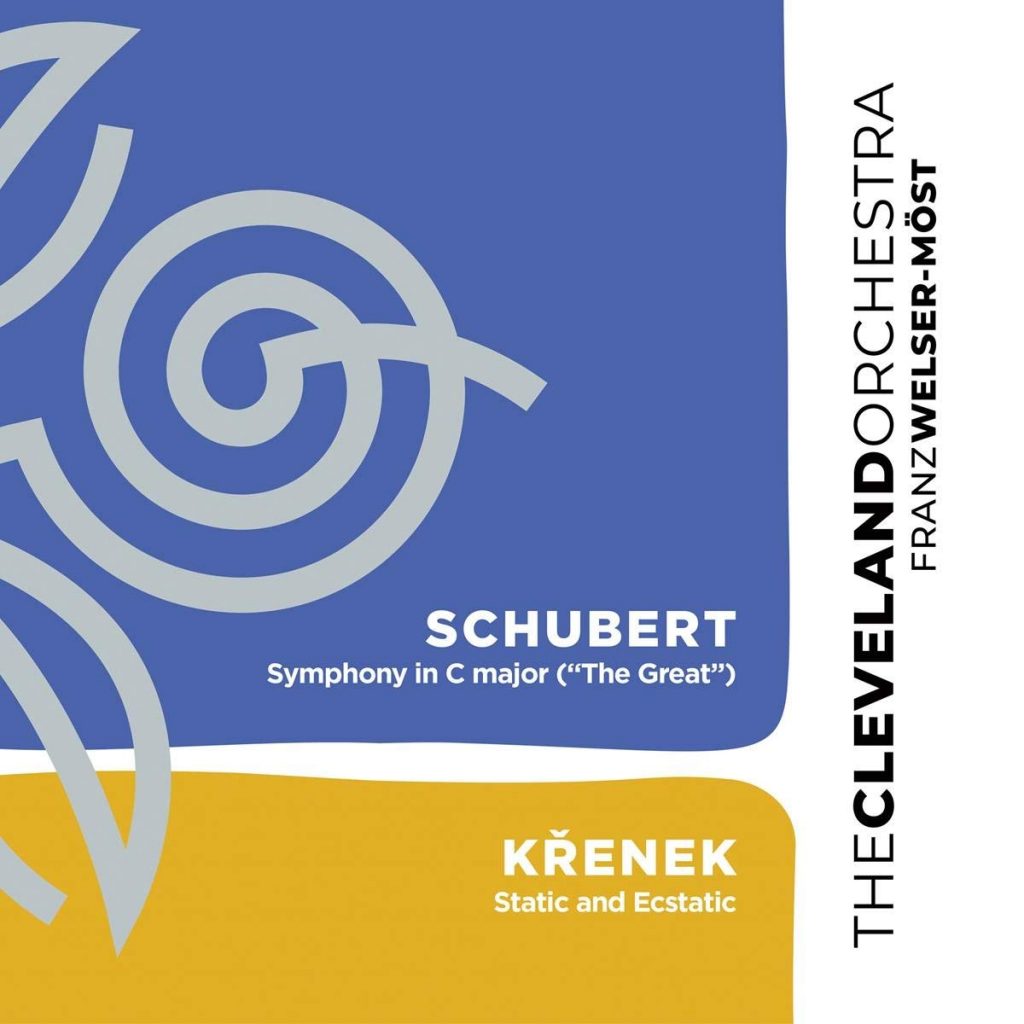

Full-length symphony orchestra concerts normally feature three works and run nearly two hours including intermission. The pandemic, which has changed so many things, has truncated programs, both to shorten possible exposure time and to avoid the social mixing of a mid-concert interval. The latest entry from Franz Welser-Möst and The Cleveland Orchestra on the ensemble’s own record label brings another high contrast into view. Franz Schubert’s spirited and expansive “Great” Symphony in C (1826) sits alongside the ten miniatures that make up

The latest entry from Franz Welser-Möst and The Cleveland Orchestra on the ensemble’s own record label brings another high contrast into view. Franz Schubert’s spirited and expansive “Great” Symphony in C (1826) sits alongside the ten miniatures that make up